This creative-critical essay frames my contribution to the colloquium: a poem entitled ‘Against Misdirection’ which forms part of my feminist adaptation project of the Old English epic Beowulf.

*

‘if text is a landscape – if reading is a form of travel – if readers are travellers – then the text is a journey in itself – if the text is a journey and a landscape – if all landscapes have paths – if each path is a choice – a desire – if this text has its own desires – there are bodies within it – yours and mine – we may find ourselves meeting somewhere inside – ’

Kim Moore, Are You Judging Me Yet? Poetry and Everyday Sexism (Seren, 2023)

*

The Old English epic Beowulf is propelled by journeys and preoccupied by borders– and their guardians. From the sea-crossings of the eponymous hero to the designation of the Grendelkin as mearcstapan (border-stalkers, 1348), Beowulf invites us to become fellow-travellers. But only on the paths designated as desirable by its masculine heroic ethos. We must keep to the well-known and well-trodden routes, be wary of embarking upon dangerous trajectories, and when the Danish king Hrothgar declares of Grendel’s Mother’s mere, nis þæt heoru stow! (that is not a pleasant place! 1372), we are expected to agree.

But travellers, in physical landscapes as well as literary texts, do not always do as they are told. This is nowhere more evident than in the ‘desire lines’ made by walkers in public space: pathways that are worn into the landscape, often in deliberate opposition to planned and paved walkways, by repeated footsteps that enact a desire to traverse a place by the quickest possible route. Desire lines cut corners as walkers refuse to be confined to authorised paths, prioritising their own journey and destination. They choose their own adventure.

The metaphorical possibilities of desire lines as modes of both creative and critical practice have recently been taken up by the poets Kim Moore and Ella Frears. Moore, in her creative-critical book Are You Judging Me Yet? Poetry and Everyday Sexism (Seren, 2023), encourages the reader to navigate their own pathway through her poems and critical reflections, rather than reading from beginning to end; she even includes a flow-chart of criss-crossing alternatives that embark from the desire line concept (9). Desire lines are also situated in Moore’s book as part of a feminist practice that privileges and encourages readerly autonomy in a world in which women, non-binary, and queer individuals are especially subject to patriarchal control and suppression, not least of their free movement in space as the work of both Finn Mackay and Teresa Pilgrim, explored below, demonstrates.

In Ella Frears’ poetry, desire lines are enacted visually and verbally on the page. In a poem such as ‘Ars Poetica with Desire Line,’ the reader is offered the choice of reading the poem traditionally from left to the right and/or reading a desire line of individual words through the centre of the poem, a pathway made evident by the clearing of space in the layout on the page. Frears’ desire lines thus make explicit the potential for readerly resistance in poetic form that also drives my own creative practice as a poet, re-drawing the creative-critical map of Beowulf and offering new poetic ways into the original narrative which foreground the desires of female characters in direct opposition to the dominant patriarchal perspective. Pathways, or lastas (tracks, traces), are also especially resonant for thinking with, or through, Old English texts because they act as a metaphor for the written word in early medieval literary culture. In Exeter Book Riddle 51, for example, the pen and fingers are imagined as wondrous creatures travelling together, leaving swearte lastas (dark tracks) and swaþu blacu (black footsteps) behind them. It is through such textual traces and narrative journeys that we encounter– and can rewrite– the past.

In my poetry sequence ‘Grendel’s Mother Bites Back’ (Primers Volume Seven, Nine Arches Press, 2024) I gave voice to Beowulf’s second antagonist in the poem– a woman who is silenced, marginalised, and made monstrous by the original text– and in my new poem written for the What is Creative Criticism? colloquium, I use Grendel’s Mother’s perspective to redraw the original narrative’s representation of the path to her mere, as expressed by King Hrothgar. In my poem I invite the reader to bypass Hrothgar’s vision of an unheore stow (unpleasant place) and to allow Grendel’s Mother to open up a new desire line to her home.

*

*

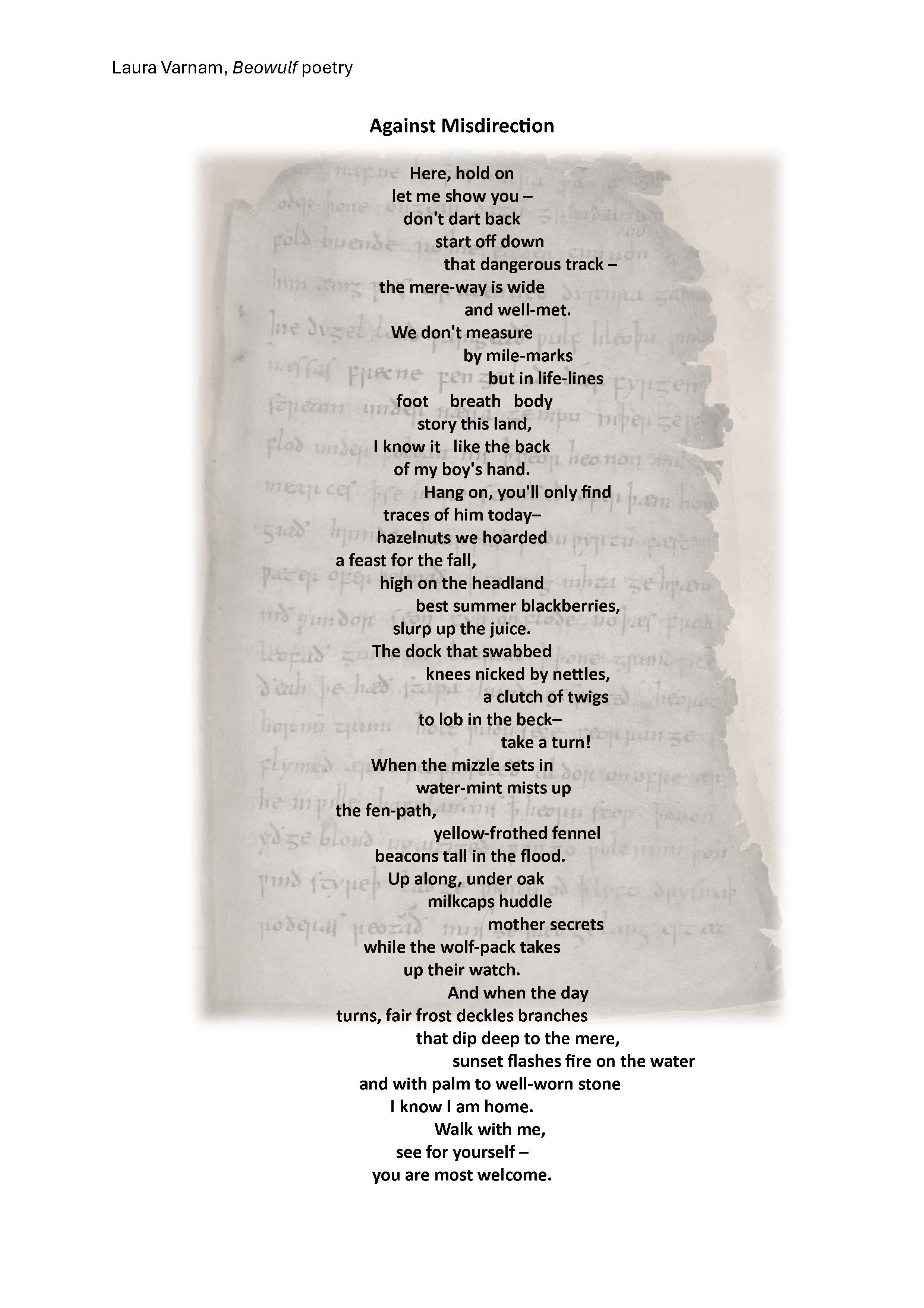

In the visual and textual strategies of this poem, Grendel’s Mother not only rewrites but ‘over-writes’ Hrothgar’s description of the path to the mere (Beowulf, lines 1357-76). Grendel’s Mother has just taken revenge for the death of her son (by entering the Danish hall, Heorot and snatching Hrothgar’s most prized advisor Æschere) and in his grief and anger, Hrothgar warns Beowulf about the treacherous journey ahead if he is to undertake the desired heroic revenge mission. The landscape that Hrothgar describes is dygel (secret, 1357), frecne (perilous, 1359), and inhabited by wolves (1358). It is plagued by hostile weather, from mists and frost to wind and storms (1358-60, 1363, 73-76), and a niðwundor (fearful wonder, 1365) is seen each night, fyr on flode (fire on the water, 1366). Furthermore, Hrothgar declares, the hæðstapa or heorot (heath-stalker or stag, 1369-70) would rather face death at the jaws of baying hounds than dare to enter the mere as an escape route. No pleasant place, indeed.

But Hrothgar’s language and imagery betrays his description as its own kind of antithetical desire line; indeed, we might even call it a ‘danger line,’ warning the unsuspecting (and male) reader away. His use of the image of the stag (or heorot), in particular, hints at the fear sparked by the female antagonist’s home because the animal shares its name with Hrothgar’s hall, Heorot, which functions as a symbol of the male heroic world, as Francis Leneghan has explored. Hrothgar attempts to control his anxiety about the mere by confidently declaring his opinion, nis þæt heoru stow (that was not a pleasant place! 1372) and couching it in a negation of the þæt wæs formula, used to cement normative, accepted wisdom in the poem. But when considered more closely, it is evident that just as the trees oferhelmað (overshadow, 1364) the mere, so too does Hrothgar’s opinion overshadow and distort the positive and generative possibilities of the natural landscape described. His vision of the mere-way is thus revealed to be both pejorative and subjective.

In my poem that is positioned ‘against misdirection,’ then, Grendel’s Mother presents an alternative, and oppositional, desire line. This is enacted in visual form by overlaying my poem across, and beyond, the manuscript page on which Hrothgar’s speech is recorded (British Library Cotton Vitellius, 163r), thereby obscuring his misrepresentation and making it unreadable. In this approach, I am indebted to the work of Diane Watt in her book Women, Writing and Religion in England and Beyond 650-1100 (2019) in which she makes the following argument about male accounts of medieval women’s lives and experiences:

Monastic writers [...] overwrote female authorities and women’s texts in the sense that they rewrote women’s narratives, replacing their oral or written accounts, the ‘underwriting,’ with new versions. Such overwriting was often intended to improve, modernize and preserve the earlier material rather than destroy or censor it [...] I also use the concept of overwriting in a more metaphorical sense to describe the complex relationship between male authors and their female subjects and to capture the ways in which texts can attempt to control and circumscribe female autonomy. (3)

My poem turns this strategy back on the male author (both Hrothgar as the speaker in the text and the Beowulf-poet himself), in order to return Grendel’s Mother’s autonomy, enabling her to describe the route to her own home for herself. Additionally, within my poem, I reimagine the details of the physical landscape as cited by Hrothgar, as well as its inhabitants and the weather (the path, the headland, the stream, the lake; the Grendelkin and the wolves; the precipitation and the sunset). Rather than functioning to warn the reader away, in my poem these details are recast as welcoming and inviting. Instead of a site of danger and alarm, my poem creates a playful and fruitful landscape that sustains Grendel’s Mother and her son, providing food, medicine, and safety. It has all the hallmarks of home.

My poem also deliberately wends its way across the page rather than cutting a direct desire line because I wanted the reader to take their time to enjoy the journey. This is a landscape that encourages the reader to pause in wonder and to visualise Grendel’s Mother’s memories of her embodied experience; to explore her ‘life-line’ rather than charting Hrothgar’s disembodied, manmade milgemearcas (mile-marks, 1362). This, moreover, represents a further element of my feminist practice because I wanted to present the mere-way as a safe space for female readers and indeed for Grendel’s Mother herself, by establishing a hospitable rather than forbidding tone. Being able to walk safely in the world is, fundamentally, a feminist issue, as Finn Mackay has explored in her book Radical Feminism: Feminist Activism in Movement (2015). The threat of male violence and harassment has repeatedly made public space unsafe for women and Mackay begins their book by discussing the ‘Reclaim the Night’ movement that began in the late 1970s in which women took to the streets after dark to protest and to demonstrate their strength and resistance. In my reading of Hrothgar’s speech, not only is Grendel’s Mother unable to describe the route in her own words, that route is itself deliberately presented as threatening. Hrothgar’s speech represents an act of violence upon the landscape and by extension upon its female inhabitant, a strategy that reinforces Teresa Pilgrim’s compelling argument that the Beowulf-poet deliberately uses the suppression and control of social and geopolitical locations in the text in order to ‘control women’s bodily and socio-political economy’ (20). My poem thus represents an enactment of Pilgrim’s ‘radical ecofeminist’ reclamation of the landscape of Beowulf.

The original poem’s patriarchal control can even be seen, perhaps surprisingly, in the weather that it describes, as Hrothgar deploys seemingly natural phenomena as part of his representation of the mere-way as innately hostile. Indeed, Finn Mackay recognises the power of such imagery in normalising oppression when she comments that in fact, male violence is not ‘a natural phenomenon, like bad weather’:

It does not just happen, it is not a fact of life; it is a fact of inequality. It has a perpetrator and a victim, it has a cause and likewise, it has a cure. The most important and relevant lesson feminism has taught us is that male violence against women is not biological, it is political. And if it is made, then it can be un-made; if it is learnt, it can be un-learnt. (11)

Hrothgar is just such a perpetrator in Beowulf, concealing the violence he enacts upon the mere-way in metaphors of ‘bad weather’ and symbols of male anxiety (the frightened stag). My poem therefore takes up Mackay’s call to ‘un-make’ Hrothgar’s hostile landscape and enact as a restorative ‘cure.’ This is effected in part by invoking the language and style of the Old English metrical charms, in particular the charms for unfruitful land and for a journey, both of which aim to reinvigorate, cleanse, and make safe the natural landscape (see The Word Exchange, 460-69, 494-97). Old English charms are frequently positioned wið a range of natural phenomena, a complex preposition with, as James Paz puts it, ‘an ambiguous semantic range, carrying both a sense of confrontation (i.e., “against”) as well as a sense of association or collaboration (i.e., working “with” someone or something)’ (230). My Grendel’s Mother poems are positioned wið Beowulf, as I explain in Primers Volume Seven (52-53), and my poem above, in its title and linguistic strategies, deliberately works wið (both against and in collaboration with) Hrothgar’s description to ‘charm’ the mere-way into a new form.

*

Charms, like poetry more broadly, are a performative genre. They aim to bring about a new, and desired, reality through their language. Therefore, rather than merely using traditional academic prose to close read Hrothgar’s speech, my poetic practice enables me to overwrite it and propose an alternative direction of travel. In order to effect this creative reimagining, however, precise attention must be paid to the original text and this process allowed me to re-consider my understanding of the mysterious niðwundor (fearful wonder) and to posit a new critical reading of the fyr on flode (fire on the water, 1364-65). For a number of years my desktop background image has been a photograph sent to me by a dear friend from a walk they undertook by a lake at dusk, just when the sun was setting behind the trees on the far bank– and the orange rays flashed on the water. One day as I gazed absentmindedly at this image, it came to me that perhaps one reading of the Beowulf-poet’s ‘fire on the water’ could be the dazzling reflection of a sunset. This image was shared with me as an invitation to join my friend (whom, at that time, I hadn’t been able to meet in person due to the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic) on their walk. My creative-critical poem offers a similar invitation of friendly companionship to the reader of Beowulf and an alternative possibility for this much discussed detail. Creative criticism is, for me, a genre that opens up desire lines in many different directions.

*

*

Walk with me. You are most welcome. And most importantly, for an act of creative-critical re-imagining, please accept this invitation to see for yourself.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Kristen Haas Curtis, Catherine Clarke and Teresa Pilgrim for feedback on earlier drafts of my poem and to Joe Moshenska and Iris Pearson for inviting me to contribute to the Creative Criticism colloquium. I am additionally grateful to Teresa Pilgrim, not only for her important article but for many generous discussions of her work which have been an invaluable part of my feminist thinking in this essay.

Bibliography

Beowulf: A Student Edition, ed. George Jack (Oxford University Press, 1994; repr. and rev.

1997).

Leneghan, Francis, ‘Beowulf and the Hunt,’ Humanities 11.2 (2022) https://doi.org/10.3390/h11020036

Mackay, Finn, Radical Feminism: Feminist Activism in Movement (Palgrave Macmillan,

2015)..

Moore, Kim, Are you Judging Me Yet? Poetry and Everyday Sexism (Seren, 2023).

Paz, James, ‘Magic that Works: Performing Scientia in the Old English Metrical Charms

and Poetic Dialogues of Solomon and Saturn,’ Journal of Medieval and Early

Modern Studies, 45.2 (2015), 220-43.

Pilgrim, Teresa, ‘Female Masculinity in the Embodied Beowulf Wetlands: A New,

Radical, Ecofeminist Approach,’ Medieval Feminist Forum, 58.1 (2022), 16-44.

Varnam, Laura, ‘Grendel’s Mother Bites Back,’ in Primers Volume Seven, (Nine Arches Press, 2024), 51-72.

- ‘Poems for the Women of Beowulf: A ‘Contemporary Medieval’ Project,’

postmedieval, 13 (2022), 105-121.

The Word Exchange: Anglo-Saxon Poems in Translation, ed. by Greg Delanty and Michael

Matto (W. W. Norton & co, 2011), ‘Remedies and Charms,’ pp.461-99.

Online resources:

The text and translation of Exeter Book Riddle 51 (Pen and Fingers) is available at the Riddle Ages website: https://theriddleages.bham.ac.uk/riddles/post/exeter-riddle-51/

Ella Frears’ ‘Ars Poetica with Desire Line’ was first published in The Poetry Review, 113.3 (Autumn 2023) and is available here: https://poems.poetrysociety.org.uk/poets/ella-frears/

Laura Varnam is a practicing poet and the Lecturer in Old and Middle English Literature at University College, Oxford. She won the Nine Arches Press Primers competition in 2023 with her Grendel’s Mother poems (publication forthcoming in August 2024 in Primers Volume Seven). She has published creative-critical work inspired by her ‘Women in Beowulf’ poetry project in postmedieval and she is working on a monograph on Margery Kempe in modern medievalism which also includes poetry as a mode of creative-critical response. She is the author of The Church as Sacred Space in Middle English Literature and Culture (2018) and the co-editor of Encountering The Book of Margery Kempe (2021).