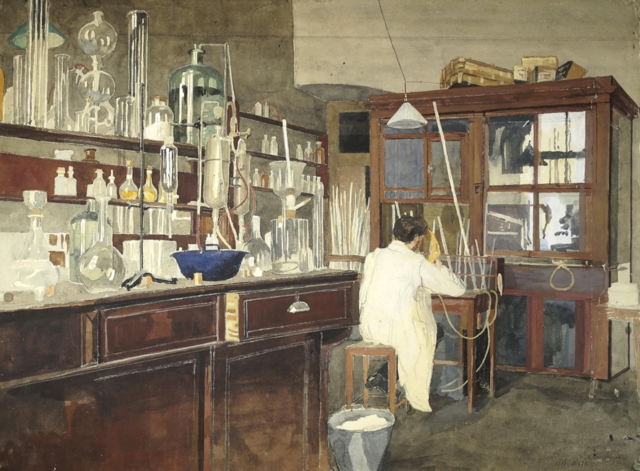

Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, Laboratory, 1915. Copyright, Wikimedia Commons.

Gabriel Flynn is a writer and co-editor of creativecritical.net

Creative Writing as Research: A Bibliography

The emergence of PhD programs in creative writing poses questions about the nature of writing, research, and knowledge, some of which have complex histories that long predate the disciplines of creative writing and English Literature. This bibliography does not attempt to address these questions exhaustively. It is aimed primarily at those who are interested in pursuing a PhD in creative writing and wishing to gain some knowledge of how such a possibility came about and find answers to some of the questions it raises. The bibliography is arranged according to a series of questions. ‘What is practice-based research?’, ‘What is creative writing?’, And ‘Can art give us knowledge?’ Under each heading, you fill find a selection of books and articles that offer accessible entry points into these. A final section lists some contemporary examples that offer different models of writing as research.

Part One: What is ‘Practice-Based Research’?

- Lisa Candy, Practice Based Research: A Guide

https://www.creativityandcognition.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/PBR-Guide-1.1-2006.pdf

Practice-based PhDs originate in Australia, where the first doctoral programmes in creative writing began in 1984. In this guide, published by one of those founding institutions, the University of Technology in Sydney, Lisa Candy outlines the history of practice-based research in the modern university and addresses in practical terms the question of how a work of creative writing might constitute a contribution to knowledge.

- Jon Cook, ‘Creative Writing as Research Method’ in Research Methods for English Studies (Edinburgh University Press, 2013)

In this chapter of Research Methods for English Studies, edited by Gabriele Griffin, Jon Cook addresses some of the tensions and paradoxes raised by the notion of a PhD in creative writing: how is that writing can be a method rather than simply a way of presenting results? Can writers be expected or relied upon to account for the unconscious processes that often generate their work? Cook addresses these and other questions via a discussion of such writers as Wordsworth and Keats, Denise Riley, T.S. Eliot, and Heidegger.

- Robin Nelson, Practice as Research in the Arts: Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013)

Nelson’s work is an influential text in the development of practice-based research. The chapter ‘From Practitioner to Practitioner-Researcher’ (pp.23-47) is particularly recommended. It emphasises how critical reflection on the process is an essential component of the research inquiry.

- Jen Webb, ‘Writing as Research’ in Researching Creative Writing (Frontinus, 2015)

Jenn Webb is one of the foremost thinkers on the relationship between creative practice and research. In this chapter from her 2015 book, Researching creative writing she draws on her work as both academic researcher and creative practitioner to address the question of how creative writing can constitute research in broad and accessible terms. She questions the relationship between creativity and method. In particular, she asks how the technical and aesthetic aspects of creative writing can be harnessed to the pursuit of a research question.

- Graeme Harper, ‘Creative writing: words as practice-led research’ in Journal of Visual Art Practice (Volume 7, 2008 – issue 2)

Graeme Harper may hold the title of the first person in the world to obtain a doctorate in creative writing. Alongside his practice as a novelist, he has written extensively on the discipline of creative writing and many related topics. In this essay, he outlines his perspective on the matter of ‘Practice-led Research’.

- Jonathan Crewe, ‘Creative Writing as a Research Methodology’

https://uwlpress.uwl.ac.uk/newvistas/article/id/150/

In a 2021 article on ‘Creative Writing as a Research Methodology’ Jonathan Crewe situates the question within a UK context. He discusses two recent, popular novels, Monica Ali’s Brick Lane and Caryl Phillips’ A Distant Shore to think through the ways that fiction can meet the assessment criteria of the Research Excellence Framework.

- Multiple authors, ‘Beyond Practice-led Research’

http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue14/content.htm

In 2012, the Australian journal TEXT, published a special issue on practice-led research. The editors contended that discourse surrounding the topic had become repetitive and an orthodoxy of sorts had taken hold. Contributors were invited to move the discussion forward. In his introduction, Scott Brook helpfully outlines various strains of criticism directed at practice-based programs on aesthetic, academic, bureaucratic, and educational grounds.

- For background reading, the following provide interesting theoretical framings of practice-based research in other arts: Peter Dallow, ‘Representing creativeness: practice-based approaches to research in creative arts’ in Art, Design, Communication in Higher Education, 2 (1 &2), 49-66 and Anna Pakes, ‘Original Embodied Knowledge; the epistemology of the new in dance practice as research’ in Research in Dance Education, 4.2 (December, 2003), 127-49).

- The Practice Research Advisory Group (UK) or PRAG-UK is a body established by members of the higher education arts research community to ‘increase the visibility and accessibility of UK Practice Research and its impact, and to make this research more searchable internationally’. Prag’s website has a blog with many more examples of practice-based research: praguk.wordpress.com

Part Two: What is Creative Writing?

- Mark McGurl, The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing (Stanford University Press, 2009)

McGurl’s history of creative writing in the American university is probably the touchstone work in the study of creative writing as a discipline. McGurl reinterprets American fiction after 1945, asking ‘how the patronage of the university has reorganized American literature and how the increasing intimacy of writing and schooling can be brought to bear on a reading of this literature.’ Although the study is largely confined to American fiction and MFA programs and therefore does not touch upon poetry and playwriting nor on creative writing PhD programs, the book contains many insights into the relationship between the university and creative writing more generally.

- D. G. Myers, The Elephants Teach: Creative Writing Since 1880, (University of Chicago Press, 2006)

The title of Myers’ book is an allusion to the linguist Roman Jakobson’s quip on learning that Vladimir Nabokov was to be offered a position teaching literature at Harvard University. ‘What’s next?’ he asked. ‘Shall we appoint elephants to teach zoology?’ Whereas McGurl’s book largely focusses on fiction, Myers’ study encompasses essayists such as Emerson and a number of American poets. He also looks further back to the creative writing’s predecessor disciplines like philology and English composition.

- Lise Jaillant, Literary Rebels: A History of Creative Writers in Anglo-American Universities (Oxford University Press, 2022)

Most recently, Jaillant’s book represents the first history of creative writing programs in both Britain and America from 1930 to the present day.

- Paul Dawson, Creative Writing and the New Humanities (Routledge, 2005)

Dawson’s book asks what the emergent discipline of creative writing tells us about English and the humanities more broadly. He situates the rise of creative writing alongside the ‘New Criticism’ practiced in universities during the mid-century and explores its development in relation to the rise of ‘Theory’ in the Anglophone world.

- Andrew Cowan, Against Creative Writing (Routledge, 2022)

Cowan’s book makes the distinction between writing, ‘what writers do’, and creative writing, ‘the instrumentalisation of what writers do.’ It explores the different roles of creative writing at undergraduate, masters, and doctoral level and argues against the disciplines coercion toward providing skills for employment in the creative industries.

Part Three: Can Art give us Knowledge?

- Berys Gaut, ‘Does Art Give Us Knowledge’ in The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics (eds Berys Gaut and Dominic McIver Lopes, Routledge, 2013)

This far-reaching question has been explored by innumerable thinkers over the years and Gaut’s essay provides an accessible entry point. She starts with the disagreement between the Platonic and Aristotelian perspectives on the ‘epistemic question’ and then offers a survey of cognitivists (those who believe art gives us philosophical knowledge) and anti-cognitivists (those who don’t).

- Eileen John, ‘Art and Knowledge’ in The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics (ed. Jerrold Levinson, Oxford University Press, 2003)

John’s essay is another accessible way into this question and brings a more contemporary perspective.

- John Gibson, ‘Literature and Knowledge’ in the Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Literature (ed. Richard Eldridge, Oxford University Press, 2009)

Gibson’s entry in this Oxford Handbook offers a broad overview of the art-knowledge question as it applies specifically to literature.

- Robin Valenza, ‘How Literature Becomes Knowledge: A Case Study’ in English Literary History Vol. 76, No. 1 (Spring, 2009)

Valenza’s essay explores the question of whether literature and literary criticism are special kinds of knowledge with particular reference to the literature of the mid eighteenth century, ‘a crucial moment in the transformation of “literature” into an object of knowledge.’

- Stathis Gourgouris, Does Literature Think? Literature as Theory for an Antimythical Era (Stanford University Press, 2003)

Gorgouris’ book offers a more detailed and wider-reaching study of the question. Drawing on a range of sources from Ancient Greek drama to contemporary novels, it asks ‘not simply whether literature thinks, but whether literature thinks theoretically – whether it has a capacity, without the external aid of analytical methods that have determined Western philosophy and science since the Enlightenment, to theorize the conditions of the world from which it emerges and to which it addresses itself.’

4. Writing as Research: Some Contemporary Examples

- Saidiya Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts’ in Small Axe, Number 26 (Volume 12, Number 2), June 2008

This essay on Venus, ‘an emblematic figure of the enslaved woman in the Atlantic world’, was published in the journal Small Axe in 2008 and may have proven to be one of the most influential examples of a scholar drawing on the methodologies of creative writing. Of her process, Hartman writes ‘By advancing a series of speculative arguments and exploiting the capacities of the subjunctive (a grammatical mood that expresses doubts, wishes, and possibilities), in fashioning a narrative, which is based upon archival research, and by that I mean a critical reading of the archive that mimes the figurative dimensions of history, I intended both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling.’

- Preti Taneja, We That Are Young (Galley Beggar Press, 2017)

Taneja’s novel is a retelling of Shakespeare’s King Lear set in modern day India, amid the anti-corruption riots of 2011 – 2012. Taneja wrote the novel as part of a PhD in critical and creative writing. It may be thought of as constituting (at least) two different kinds of research discussed above: research into Shakespeare and research into contemporary Indian society.

- John Schad, The Late Walter Benjamin (Bloomsbury, 2013)

Schad’s novel juxtaposes the life and death of Walter Benjamin and a working-class council estate on the edge of London in post-war Austerity England. The novel centres on a man who claims to be Walter Benjamin, and only ever uses words written by Benjamin, apparently oblivious that the real Benjamin committed suicide 20 years earlier whilst fleeing the Nazis.

- Mathelinda Nabugodi, Shelley with Benjamin: A Critical Mosaic (UCL Press, 2023)

‘In a series of playful close readings, Mathelinda Nabugodi unveils affinities between two writers whose works are simultaneously interventions in literary history and blueprints for an emancipated future. In addition to offering fresh interpretations of both major and minor writings, she elucidates the personal and ethical stakes of literary criticism. Throughout the book, marginal annotations and interlinear interruptions disrupt the faux-objective and colourblind stance of standard academic prose in an attempt to reckon with the barbarism of our past and its legacy in the present.’

- Ewan Fernie and Simon Palfrey, Macbeth, Macbeth (BC Editons, 2016)

A collaboration between two of the world’s most eminent Shakespeare scholars, Macbeth, Macbeth is a unique mix of creative writing and literary criticism that charts a new way of doing both. The book is published by Beyond Criticism Editions, an imprint of Boiler House Press dedicated to ‘new forms for new thinking about literature’.

- Redell Olsen, weather, whether radar: plume of the volants (ethical midge/electric crinolines, 2021)

This volume is the product of a collaboration with the BioDare group at Leeds University, Opera North and the Tetley. It uses text, visual images, and songs to explore the possibilities of a poetic, creative-critical and visual engagement with the BioDar research team’s rereading of weather-data collected by the UK’s weather radar network. This archive of data, collected to record weather, accidentally also mapped insect life. Olsen’s poetic practice explores how to engage with scientific data (and cross-disciplinary academic expertise drawn from the fields of biology, ecology, physics and atmospheric science) and how to frame related ecological, historical and cultural concerns.