In seeking out creative-critical methodologies, many writers have acknowledged a need to walk away from linear arguments and teleological narratives. Nicholas Royle has described the ‘veer’ of creative-critical writing, and Benson & Connors have investigated a ‘discipline of the break’ in creative criticism. [1] Personally, I’m a literal person and a visual thinker. When I think about the break of creative criticism, I have a vivid memory of a series of printed images, representations of broken and unfinished bridges that I came across while researching the Dalziel Archive in the British Museum, an archive of wordless artists’ proofs which continues to inspire my work (figure 1). [2] I remember distinctly the satisfaction of finding these engravings in the archive, with all that they conveyed to me about catastrophic disjointedness and incomplete communication. Gathered unlabelled in a scrapbook of illustrations, divorced from publication contexts, these prints became something new, beyond the architectural diagram or disaster narrative. A half-bridge has something to say about derailed communication. About the way epistemological structures can be undone, as illustrations escape from their origin text. Disconnected from the books or magazines they once belonged to, the archived prints both connected and disconnected with each other, and with writing. They became a new symbol of narrative: incomplete, but nonetheless going somewhere. A story is catastrophically halted, and in the process, a different one emerges.

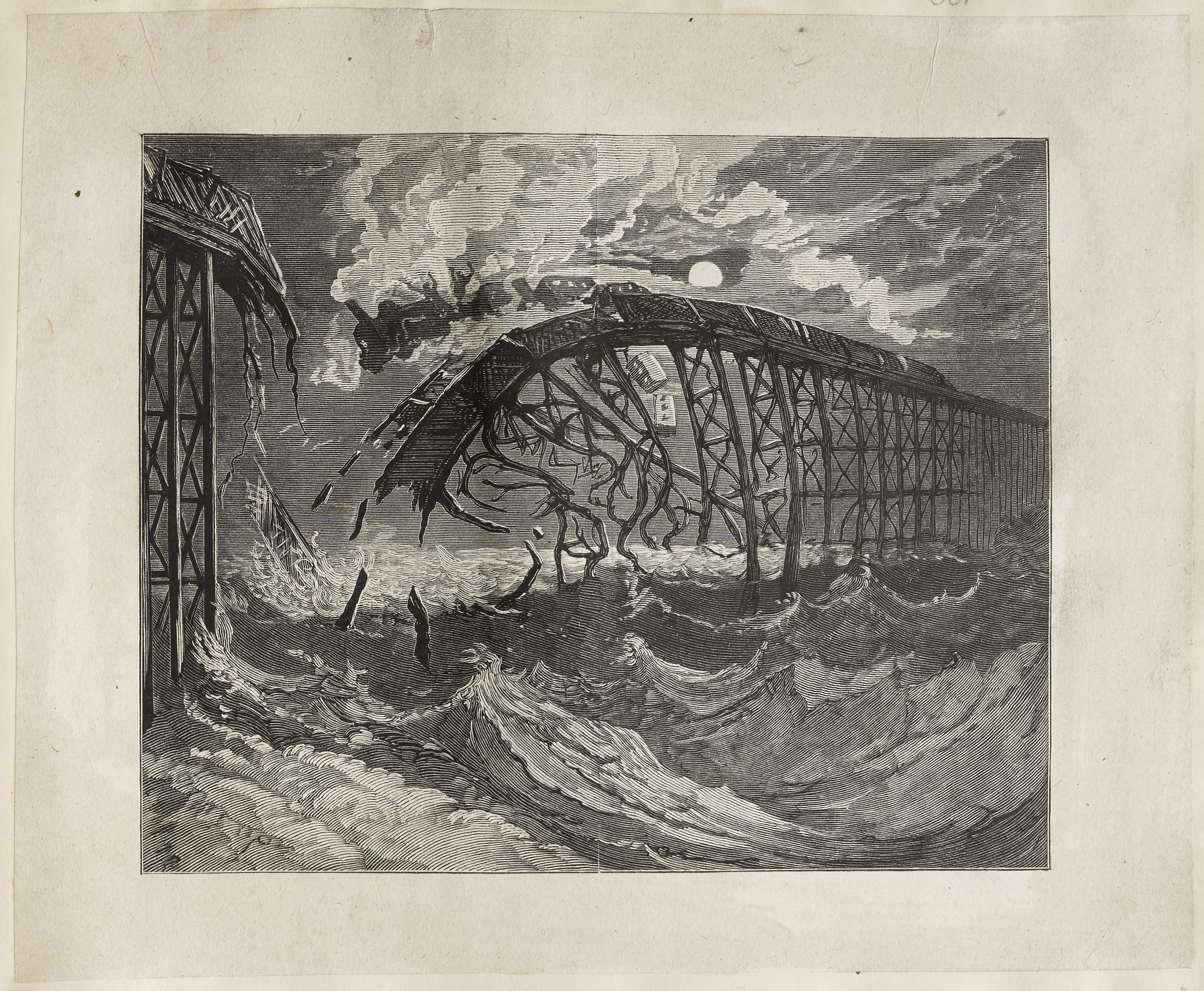

Figure 1 Dalziel Brothers, wood-engraved illustration of a collapsing bridge. Dalziel Archive Volume 40 (1880), 1913,0415.201, no. 601 . Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the British Museum. All Rights Reserved. © Sylph Editions, 2016

This bridge that refused to bridge spoke to me about the creative potential I sensed in the archive itself, which can present the researcher with an overwhelming mass of material, but does so in a way that is disparate and non-linear, providing no progression, no connections, no organised sense or narrative. The landscape of the archive – sometimes fascinating, sometimes violent – is one where we are invited to find our way without bridges. For me, especially thinking about historical and archival approaches, the break is in part a break of logic. Creative criticism requires us to attempt what is very difficult: to work diligently and ethically with historical material, but also be ready to harness our research to improper tales that seem wild or unsayable.

Saidiya Hartman’s 2008 essay ‘Venus in Two Acts’ stands out for me and for many readers among the most brilliant commentaries on creative responses to archives. Confronting the impossibility of writing about two enslaved Black women who died in 1792, Hartman described ‘the pain experienced in [her] encounter with the scraps of the archive’. [3] But given that ‘the archive is inseparable from the play of power’, the urgent question of her essay becomes: ‘Is it possible to exceed or negotiate the constitutive limits of the archive?’ [4] There follows an outline of a writing method Hartman called ‘critical fabulation’, a ‘history written with and against the archive’. [5] Importantly, Hartman demands a resistance to the cliché of writing into archival absences, and avoids the temptation ‘to fill in the gaps and provide closure where there is none’. [6] Instead, she set out to ‘exploi[t] the capacities of the subjunctive (a grammatical mood that expresses doubts, wishes, and possibilities), in fashioning a narrative, which is based upon archival research’, in order both ‘to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling’. [7] Hartman’s ‘critical fabulation’ method has been hugely influential and has prompted much new work (including prompting archivists such as Michelle Caswell and Anne Gilliland to propose new methods of archival practice). [8] Its influence has been particularly felt in fields of history, memory and archive studies; it is equally important to emerging discussions of creative criticism, a form of writing for which Hartman can propose a bewildering and yet well-tested methodology. It sits alongside other theoretical works that help us understand how creative criticism offers methods for countering problematic mainstream cultures of knowledge. Benson & Connors championed creative criticism through their urgent parody of the traditional assessed essay, pointing out that the essay begins with the ‘question of whether or not to accede to the workings of… institutionalised demand’. [9] Nicholas Royle has reminded us: ‘critical and creative writing is necessarily at war, writing in the midst of war, first of all perhaps as a warring in and over language’. [10] For these writers, creative criticism is implicated in – but is also able to creatively and even heroically challenge – those structures of institutionalised knowledge that rule us all.

I became interested in how to write about mainstream archives recently when I wrote The Wood Engravers’ Self-Portrait . It’s a book that is entirely focused on a large visual archive, an archive comprised of proofs of the oeuvre of the Dalziel Brothers, the leading image-makers of Victorian Britain. While researching the book, I often felt frustrated by how the archive was so large, sprawling and universalising (they made 54,000 prints over 5 decades), and yet also by everything that was left out: I was conscious of the people whose stories were left untold or briefly sketched, or who were represented in derogatory, distorting ways. For me this became an invitation to write history differently, askew. Investigating print culture supposedly ‘authored’ by famous canonical artists and writers, I avoided focusing too much on their stories, instead seeking to illuminate the lives of precariously employed artisans who perhaps had a minor role in engraving or delineating an image. For instance I wrote a chapter about a large body of illustrations to Charles Dickens’s novel Barnaby Rudge , making those illustrations tell the story, not of Dickens, but of junior employees in the image factory. Finding only skeletal archival details about the lives of these print-workers, I wrote about them by doing literary criticism, but doing it askew.

The Dalziel Archive is an overwhelming visual archive of 54,000 wood engravings, and the excesses of this archive continue to make their intellectual and imaginative demands on me. While I was researching it, I read numerous Victorian novels, seeking immersion in the print culture I was investigating. Such an immersion in mainstream Victorian culture was often darkly disturbing, and I’m still working on creative methods for responding to this experience. Another work in progress is a graphic novel, Nick’s Life in Scraps: A Mad Queer Archive Story , in which I respond to the archival research through creative collage. Sample pages from this work are included below this article.

The collage form works for me because it takes a fragmentary approach to visual and verbal narrative; in its fragmentary nature, it refuses to close archival gaps. For me, this has given rise to some interesting creative methods and new research questions. From the start, I realised it would be impossible for any of the characters I created to have the same face as the novel progressed. This lack of facial continuity became exciting to me, an opportunity to present people differently. I have mild face blindness, enough that I find it difficult to follow film and television narratives, and to meet new people. I do recognise those I know well, but facial recognition is difficult for me without contextual information. When collaging, I found that being able to use multiple faces for my characters was enabling; characters could be embodied in different ways as we saw them in different moods, moments or aspects. I liked the way the collage form could challenge fixed identities of visualised personhood. Recognition wasn’t as important as the other things we might see in a face. In figure 3 we see the narrator as an old man, looking back on his life as a fashionable young socialite. In figure 4 he introduces the people who have been important in his life, and the idea of the face is introduced (and literally exploded).

The letterpress from which written elements are collaged in my work is mostly Ellen Wood’s East Lynne . It’s a novel that is surprisingly poetic in its sensationalism: I felt arrested by its language. It is also a text that can feel outrageously conservative as you read it. It’s wildly hetero- and gender-normative, the hero a stereotype of Victorian masculinity, and the villain an effeminate man. Having been immersed in a mainstream print archive as a lesbian woman, and rarely seeing myself there, I had an urge to queer Wood’s text, using what I could find to do that. There was a lot available, from images of bodybuilding and men’s fashion, to spiritual masculinity and intimacy, so I started creating a story of queer love, which you can see emerging in figures 5 and 6. It’s also a story of mental ill health, isolation, and inadequate care (figure 7), an angry response to the worlds I saw both within and without the archive.

This isn’t a project of using creative work to complete a historical record. Instead it’s a personal text in which I respond through visual and verbal quotation to research material that I’ve worked with, material that I’ve already written about in creative-critical academic articles and a monograph, but that still occupies my mental landscape. It is always important to me to acknowledge the role of the self in my narration, and just how partial the work is as a creative-critical response. So I made the text’s narrator an autobiographical scrapbooker (figure 8), whose coat of arms is a broken mirror, and who cannot write his own story but reveals himself in the words and images he scraps from elsewhere. I’m not sure how this will end, but it’s part of an ongoing attempt to figure out how critical thinking and historical research connect to our imaginative lives.

Figures 2-8 Sample pages (non-continuous) from Bethan Stevens, Nick’s Life in Scraps: A Mad Queer Archive-Story , collaged graphic novel (in progress). Actual page size: 255mm (h) x 200 mm (w).

Wood engravings all by the Dalziel Brothers, from the Dalziel Archive. Text from Ellen Wood’s East Lynne and other Victorian literary texts. Images reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the British Museum. All Rights Reserved. © Sylph Editions, 2016

[1] Nicholas Royle, Veering: A Theory of Literature (Edinburgh University Press, 2011), passim; Stephen Benson and Clare Connors (eds), Creative Criticism: An Anthology and Guide (Edinburgh University Press, 2014), pp. 1-47.

[2] For my creative-critical monograph on this archive, see Bethan Stevens, The Wood Engravers’ Self-Portrait: The Dalziel Archive and Victorian Illustration (Manchester University Press, 2022).

[3] Saidiya Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts’, Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008), p. 5.

[4] Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts’, pp. 10-11.

[5] Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts’, pp. 11-12.

[6] Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts’, p. 8.

[7] Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts’, p. 11.

[8] Anne Gilliland & Michelle Caswell, ‘Records and their imaginaries: imagining the impossible, making possible the imagined’, Archival Science, vol. 16 (2016), p. 23.

[9] Benson and Connors (eds), Creative Criticism , pp. 2, 10.

[10] Royle, Veering , pp. 68, 72.

Bethan Stevens is a Reader in English & Art Writing at the University of Sussex. She has recently collaborated with the Prints and Drawings Department of the British Museum on the project ‘Wood Engraving and the Future of Word-Image Narratives: The Dalziel Family, 1839-1893’ (AHRC), which focuses on the largest publisher of printed images in the Victorian period. The project’s outputs have included a monograph (Manchester UP, 2022), an outreach initiative entitled ‘Beyond the Archive’, an illustrated catalogue of the Dalziel Archive on the British Museum’s database, an exhibition at the British Museum (2022), and a graphic novel. She is also interested in Blake, and her creative-critical essay on Blake and the theory of captions was published in Beastly Blake (Palgrave, 2018).