Oooh.

Of course.

Well, yes (French, Italian, neo-Latin? Polly; Monty; Diderot)

Dialogues? Collaboration (voice without self)?

Rediscovery of serio ludere?

These notes, which I took during the What Is Creative Criticism? colloquium, were not my finest intellectual jottings. They would provide scant material for the unfortunate doctoral student in 2074 researching the notebooks and methods of early 21st-century comparatists.

Or would they? Let’s put them alongside notes taken at another academic gathering, which I won’t name, for reasons that will be clear to you:

FFS.

What’s your point?

Une évidence.

Sainsbury’s: prunes; potatoes; sausages; muesli; Paws.

If, here, my mind has turned to my empty store cupboard, at least I was still awake. At some seminars we are expected to listen to someone reading out words written to be read not heard, for 50 minutes at a stretch, delivered at speed or in a voice that has thought little about audience, our only prop (or prompt) the false clarity of Powerpoint slides or a terribly presented handout. At conferences in France, running well over 50 minutes is not unusual and back-to-back papers allow little allowance for the bodies in which our critical minds are housed. At one colloquium in Paris, inefficient chairing meant the audience had no break in four hours: we are, apparently, dead from the stomach down. Such testing formats have led me to develop some face-saving techniques. Older (and mostly male) academics, I learned when still a doctoral student, are allowed to close their eyes sagely while listening. Instead, I adapt Madame de Merteuil’s testing of her self-control, as depicted so memorably in Laclos’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses: to practise cloaking her feelings in high-society settings, Merteuil stabs her hand with a fork beneath the table as she feigns interest in the conversation. My research shows that the Bic Clic Stic has just the right level of point to its nib to do the job.

Listening to conventional academic papers is always tiring, can be boring, and requires a certain physical steel. Conferences are the most common site for me to question what I’m even doing in academia, a feeling exacerbated since I became a mother and every moment when I’m not hanging out washing, hiding veg in tomato sauce, or arranging accessories in the Sylvanian Families Pony Salon becomes a precious chance (too often squandered on admin or marking) to think (and be who I used to be). I used to assume that finding it tricky to focus was wholly my failing. The creative-critical approach allows me to see otherwise.

I wasn’t bored! Not very critical, this observation. But it matters. The very different ways the authors inhabited their contributions at What Is Creative Criticism? shared an important trait: they gave something to us in the audience. They lent on biography and humour. They sought responses from us that were not (or not only) about admiration at erudition, fierce argumentation, or proof, but about feeling, interest, and being spurred to react to texts instinctively. They came out of or were forms of research but also did the best kind of teaching in offering suggestions for how we might, in turn, be inspired to work, opening up, modelling, enabling imitation.

My life beyond the mind – viz. needing to pick up my little girl – meant I didn’t get to see all the papers. So the two questions with which I now end this (what? eulogy-cum-life-writing-lite-lament?) might have been answered by what I missed. But:

1. Can we make sure that creative criticism doesn’t rely, implicitly or explicitly, on givens about genre that are in fact relatively recent historically (so says the early modernist, and a French-Italian-neo-Latin one at that, who knows how hybrid and mixed and, frankly, odd, 16th-century writing could be, and not just in the famous case of Montaigne’s Essais)?

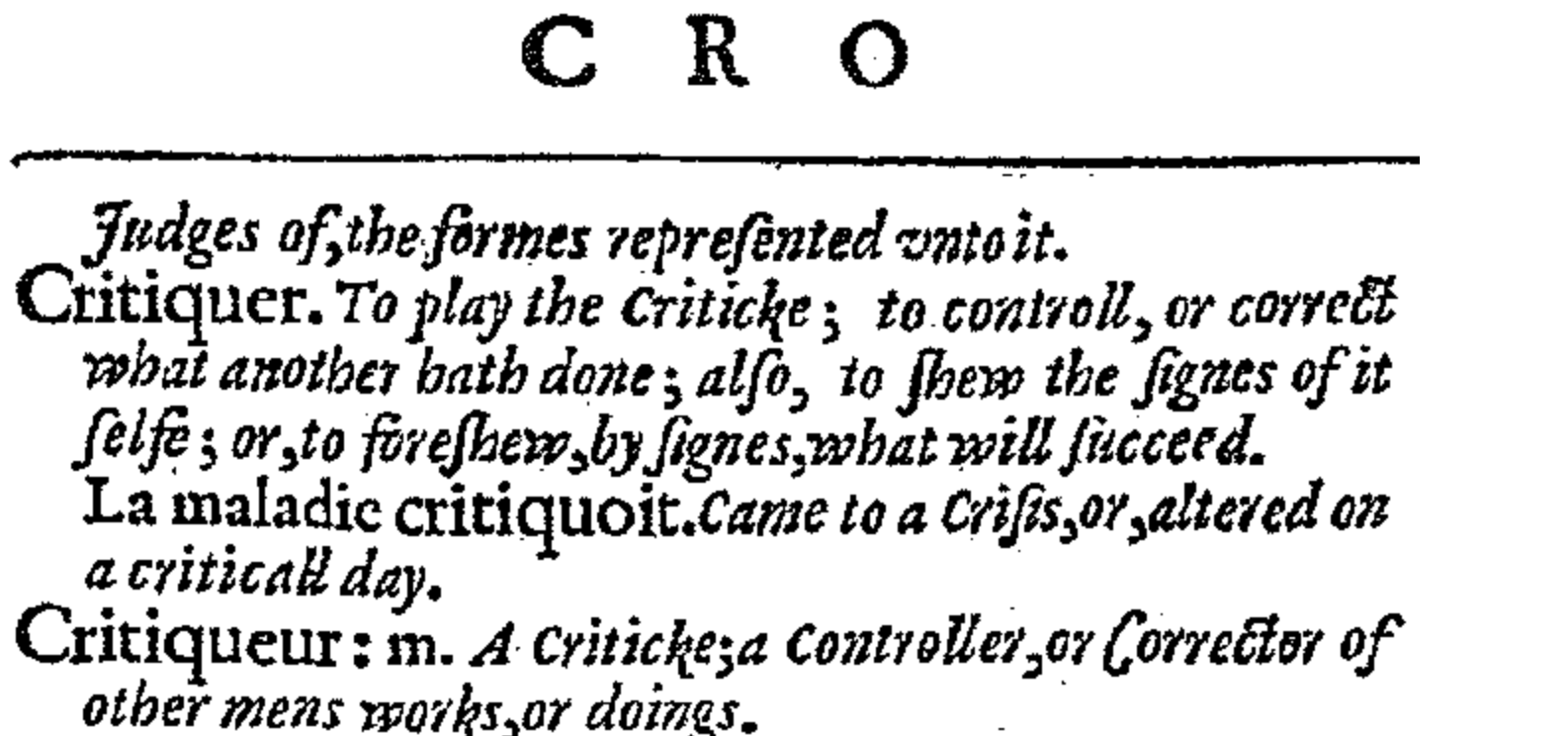

2. If we are looking to move beyond Randle Cotgrave’s emphasis in his gloss below on the critiqueur as a corrector, can we at the same time pick up on what he writes for ‘critiquer’ and play the Criticke, assume a role, take on other voices? That is (and I write this aware that what I’ve written above is rammed with details about me) can we, perhaps inspired by the inventions of Renaissance dialogue, find more ways of doing creative criticism without bringing ourselves on to the page?

Randle Cotgrave, A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues (1611)

Rowan Tomlinson is Senior Lecturer (Associate Professor) in Comparative Renaissance Studies in the School of Modern Languages at the University of Bristol, where she directs the BA in Comparative Literatures and Cultures.