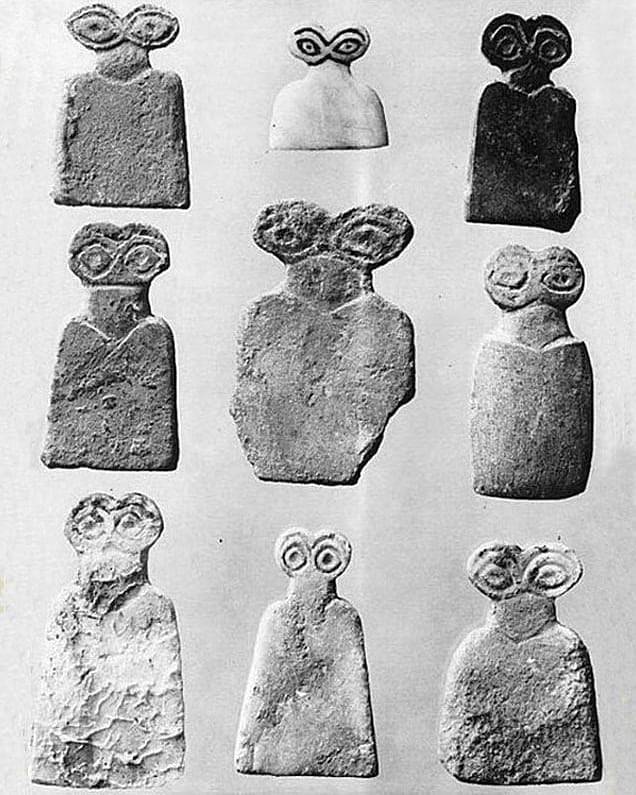

Image: Tell Brak Eye Idols in the UCL Institute of Archaeology. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Gregory Leadbetter is a poet and critic. His research focuses on Romantic poetry and thought, the traditions to which these relate, and the history and practice of poetry more generally. His monograph Coleridge and the Daemonic Imagination (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) won the University English Book Prize 2012. His books of poetry include Balanuve (with photographs by Phil Thomson) (Broken Sleep, 2021), Maskwork (Nine Arches Press, 2020; longlisted for the Laurel Prize 2021), The Fetch (Nine Arches Press, 2016) and the pamphlet The Body in the Well (HappenStance Press, 2007). A new pamphlet, Caliban, is forthcoming with Dare-Gale Press in spring 2023. He is Professor of Poetry at Birmingham City University.

1. To contemplate afresh the relation between the ‘creative’ and the ‘critical’ is to recognise a long conventional – and still highly influential – contrast between these terms within the history of criticism. This is partly a legacy of various literary, intellectual, and material currents that came into focus in Britain and elsewhere in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In simple terms, this saw the rise of a certain kind of reviewing culture on the back of an explosion in printing and publication comparable to the rise of the Internet in our own time – a reviewing culture in many ways at odds with the contemporary flourishing of new and revitalised ideals of what literature can do for us as human beings: ideals that, later in the nineteenth century, became associated with the word ‘Romantic’ and the idea of a Romantic movement. A jokey epigram by Coleridge, published anonymously in 1801, encapsulates some of these tensions nicely:

Most candid Critic!—what if I,

By way of joke, pull out your eye,

And, holding up the fragment, cry,

Ha! ha! that men such fools should be!

Behold this shapeless Dab!—and he,

Who own’d it, fancied it could see!—

The joke were mighty analytic;

But should you like it, candid Critic?

2. The relationship between the ‘creative’ and the ‘critical’ was not a straightforward division into two distinct groups, however, but ran through and within the writers of that period. As such, that relationship became a site of contention at one and the same time as the sense of a difference between these two ‘faculties’ was thrown into fresh relief (I say ‘faculties’ because faculty psychology was a prevailing norm in discourse of the time).

3. I read these conditions as a coming-to-consciousness of this now familiar distinction (often ranked, rendered in hierarchical relation, with ‘creative’ the superior) – but as a distinction that acted as the necessary precursor and indeed motivating impulse to a synthetic reconciliation of the two (the creative and the critical): a dissolution that, in practice, enabled and inspired fresh and further recombination. In other words, a fresh awareness of the relation between the creative and critical as dialectic, in vital ways mutually involved, mutually propulsive, mutually productive. The conversations that we continue to have regarding that relation – like those of Matthew Arnold, T.S. Eliot, R.P. Blackmur, and others since – are descendants of that moment.

4. The reconciliation of necessary distinctions – the distinctions that make possible variety, individuality, difference, and which therefore also create the very grounds, difficulties, and possibilities of communication and interaction – is at the heart of Romantic thought, particularly in Germany and England. ‘To reconcile therefore’, Coleridge wrote in his notebook in October 1804, ‘is truly the work of the Inspired!’. We find in Friedrich Schlegel, too (to take just one other example) both a vivid sense of distinction and a vivid sense of reconciliatory, mutually productive relationship. These writers participated in the sense of fracture that continues to haunt the words ‘creative’ and ‘critical’, but their work at the same time yields homeopathic clues to reconceiving the relation of the creative and the critical as a radical continuum: ‘radical’ in its etymological sense of ‘at root’.

5. What I have in mind is not an absolute, collapsing different kinds of practice into sameness, but an ethos – an open-ended method or way of proceeding – characterised by identifying shared purposes at the root of the creative and the critical, which cross boundaries of literary and intellectual form and indeed cross-pollinate, helping to grow on forms of writing and thinking that may (or may not) differ from the form that stimulates that growth.

6. This ethos has grown out of questions that have affected and informed my own work both as a poet and critic. It is the relation that I have had to forge, in practice, between the creative and the critical (in all their tensions, as conventionally conceived), in order to proceed and cohere, to my own satisfaction, as a poet-critic. The questions loomed from the writings of those I read from my teens. In a letter of 1801, for example, Coleridge writes: ‘Davy in the kindness of his heart calls me the Poet-philosopher—I hope, Philosophy & Poetry will not neutralize each other, & leave me an inert mass’. We could replace the word ‘philosopher’ and ‘philosophy’ with ‘critic’ and ‘criticism’ there. Ted Hughes gives an account of falling asleep over an unwritten undergraduate Eng. Lit. essay, and having a dream of a burnt fox that slammed its bloody handprint onto the blank page and said: ‘Stop this – you are destroying us’. That became a foundational myth of himself as a poet, for Hughes – damagingly so, I have argued elsewhere. How, then, to avoid the creative and the critical from neutralising or even destroying each other? How to avoid an impasse or collapse? Simply asking the exploratory question, then, ‘What is the relation between the creative and the critical?’, is productive in itself: apt enquiry is half of wisdom, as Francis Bacon put it. My own response to these dilemmas and tensions has of course both conditioned and been conditioned by the foci of my research, in many aspects of which I have found those dilemmas and tensions played out.

7. My situation, working in the context of the academy, is of course relevant here, because the relation between the creative and the critical has been refracted through the institutional history of the university and its employees. Ted Hughes’s account of his dream is a kind of comment on the way that history had developed, at least as he found it. I wonder what Hughes would have made of this, by A.E. Housman, at his inaugural lecture as Professor of Latin at Cambridge in 1911:

Scholarship, that study of the ancient literatures for which chairs of Greek and Latin are founded, is itself a department (as I said before) not of literature but of science; and science ought to be scientific and ought not to be literary. The science, though it has works of literature for its subject, does not make its appeal to the same portion of the mind as do those works themselves. Scholarship, in short, is not literary criticism; and of the duties of a Latin Chair literary criticism forms no part.

Housman here speaks for the virtues of distinction. Rather than bringing his various literary and intellectual practices together, he was very keen to keep them separate and, in effect, to compartmentalise his life and practice as a scholar and poet: something he may have found personally and professionally liberating (he was good at compartmentalising). In poetry, he advocated an all but unconscious model of poetic creativity (see his 1933 lecture, ‘The Name and Nature of Poetry’) – apparently a stark contrast to what he says here. He considered himself a connoisseur of poetry, but had an almost superstitious aversion to betraying its mysterious sources.

8. Housman’s opposition between the ‘literary’ and the ‘scientific’ in his 1911 lecture is another analogue to the conventional opposition between the creative and the critical. Housman was speaking at a time when literary studies were increasingly justifying themselves in terms of a newly dominant scientism, with which critics often sought to associate their studies through a scientistic vocabulary and attitudes that laid claim to ‘objectivity’ – in unspoken compliance to a hierarchy of ‘utility’ that we are still having to deal with today. But Housman is actually making a further distinction here, between ‘scholarship’ as ‘science’ on the one hand – which for him involved the painstaking examination and technical reconstruction of ancient texts – and ‘literary criticism’ on the other. He associates the latter, by implication, with the appeal and interest of literary works. Literary criticism and literature are in fact grouped together by Housman. Indeed, he had a high regard for literary criticism. Turning down the invitation to give the Clark Lectures at Trinity College Cambridge in 1925, he wrote that ‘literary criticism, referring opinions to principles and setting them forth so as to command consent, is a high and rare accomplishment and quite beyond me’. So even Housman, in his distinctions between ‘scholarship’ and ‘literary criticism’, and between ‘science’ and ‘literature’, finds a bridge between the creative and the critical in a literary context. It takes a bit of work to winkle that out, however, and the idea that different branches of the humanities – let alone when the arts are brought into consideration – appeal to entirely different ‘portions of the mind’ remained, and remains, influential and normative, and the distinction and relation between the creative and the critical continues to be shadowed by that.

9. The dichotomy is analogous to what Eliot identified as the ‘dissociation of sensibility’ in English poetry after the seventeenth century. Eliot admired the interfusion of thought and feeling in the ‘Metaphysical’ poets, which equated to a ‘direct sensuous apprehension of thought’, and lamented the split that he observed:

it is the difference between the intellectual poet and the reflective poet. Tennyson and Browning are poets, and they think; but they do not feel their thought as immediately as the odour of a rose. A thought to Donne was an experience; it modified his sensibility. When a poet’s mind is perfectly equipped for its work, it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience

Not for the first or last time, Eliot was in several ways closely echoing Coleridge here, who – with great self-insight – wrote as early as 1796 that ‘My philosophical opinions are blended with, or deduced from, my feelings: & this, I think, peculiarizes my style of Writing’. Coleridge the reconciler would later abstract a principle from this insight into his own experience, in his Biographia Literaria: ‘No man was ever yet a great poet, without being at the same time a profound philosopher. For poetry is the blossom and the fragrancy of all human knowledge, human thoughts, human passions, emotions, language’. In Coleridge, thought and feeling recognise their own intimacy at a radical (root) level – and poetry is at once an origin and outgrowth of their radical continuum.

10. In fact, the creative/critical distinction stands as a kind of metonym for many conventional, historically influential distinctions – not just between feeling and thought, poetry and philosophy, the Romantic and the Classical, unconscious and conscious, non-conceptual and conceptual, non-rational and rational, inspiration and intellection, mythos and logos, nature and art – refracting deep into European culture. So, the stakes here are high: the relation between the creative and the critical stands at the nexus of matters that, as Coleridge found, rapidly ramify into fundamental questions of human psychology and self-cultivation – revealing fundamental connections between poetry and metaphysics.

11. Having signalled the directions in which I, too, think these questions lead, I won’t go into all of those here (that is the work of a book or two) but instead bring them back to conclude with some key aspects of the practical ethos that I’m describing, that seeks to hold the creative and the critical – and by extension those other binary distinctions that I’ve just mentioned – in a radical continuum.

12. For me, the common root is found in the impulse to speak and to know, and to know through the action of speech and language – that is, a desire to know and experience, coeval with the impulse to speak and communicate. A zetesis (an ancient Greek word meaning seeking, inquiring) coeval with the act of making and knowing, poiesis and gnosis. That’s one principle: the interfusion of zetesis, poiesis and gnosis. This can be read as a kind of primal mutuality, an interfusion to which the relation between the creative and the critical directs us.

13. These processes manifest and embody in multiple ways: their very realisation is made possible by and leads to difference and diffraction in form. Turning again to Coleridge, this process of differentiation and diffraction can be conceived by analogy with the principle of polarity, in which differentiation evolving from a common power involves ‘a tendency to re-union’. To put it another way, the continuous evolution and realisation of these differing forms – say, for example, a poem and a critical essay – proceeds in dialectical relationship. This can also happen at a verbal level: Coleridge coined the word ‘deynonymisation’, the differentiation of terms, not as a precursor to an absolute re-synonymisation, in which they would simply collapse back into one another, but to synthetic, relational thinking. The distinction between the creative and the critical may in some ways be enabling and revealing – but so is their synthetic, relational, dynamic interfusion. Coleridge keeps in play both the virtues of distinction and the virtues of mutually propulsive relationship.

14. This in turn draws our attention to our own position and contingency within a given social, historical, intellectual and cultural context, because it requires us to recognise that position as one of relation – and an ethical relation, at that. This banishes illusions of an absolute objectivity, which are now being dispersed even in the natural sciences, at no loss to the value of the work undertaken in those sciences. The knower is involved in the known.

15. This has consequences for criticism, not least because it enables us to recognise a reading – that is, a critical apprehension, account, or evaluation – as something that is made as well as found: indeed, the finding and the making occur simultaneously. A reading is what the critic makes of a work, as it works upon the critic – and this in itself becomes a medium for further active contemplation. Criticism is not neutral or merely denotational, but constitutive, performative, normative, and necessarily selective. It filters and directs attention. A reading (in whatever form) is a vision, a way of seeing. It can, like a poem – which is also a kind of reading – move minds and feelings. It is possible, then, to have what I’d call a generative criticism – which, while it may be ‘about something other than itself’, as Eliot put it, is also (and here I’m disagreeing with Eliot) about itself. I agree more with R.P. Blackmur: ‘the critical act is what is called a “creative” act, and whether by poet, critic, or serious reader, since there is an alteration, a stretching, of the sensibility as the act is done’. Conceived in radical continuity with the ‘creative’, the ‘critical’ participates in the work of stimulating, kindling – the giving, as it were, of an eye and ear, taste and insight.

16. For art itself, this radical continuum enables what are often regarded as unromantic pursuits – scholarship, learning, criticism – to be conceived as integral and indeed vital to the creative process. It allows for, in Coleridge’s words, the ‘interpenetration of passion and of will, of spontaneous impulse and of voluntary purpose’. Art and nature, will and imagination, thought and feeling, conscious and unconscious, conceptual and non-conceptual, rational and non-rational, intellection and inspiration, logos and mythos, critical and creative, are not crudely dichotomised, but conceived in productive interaction.

17. Two further key principles follow from this. First, the point of origination is also a point of relation. However original, and however we conceive of originality, origin is also relation. Second, what Ben Jonson called Ingenium, the poet’s ‘natural wit’ and ‘instinct’ – the poet’s spontaneity, in a sense – can, and should, be educated. The spontaneous powers of the poet can and should be nurtured, informed, cultivated.

18. That leads me to my final point, which is to say that in this idea of the creative and the critical as a radical continuum, with a shared purpose, lies a broader educative principle that unites the arts and humanities (indeed, not just the arts and humanities) – that emphasises once again the cultivation of our humanity, our qualitative being and values, our eunomia, or well-being, as a species and as a society of societies – in opposition to the crudity of quantitative thinking, a greed refracted into a totalising, global economic hegemony that tends to reduce human beings to means rather than ends in themselves.