Introduction

In the final week, we turn to the haiku, a well-known but often not well-understood form of ancient Japanese poetry, as well as other Japanese forms such as the haiban and the renga. The haiku form was created by a group of Japanese 17th century poets, who built on a tradition for shared poetry which had existed for hundreds of years before them. The most famous of these was Matsuo Basho, whose simple and natural style set the template for much Japanese poetry. Basho and his contemporaries also picked up on elements from the Tang period of Chinese poetry, connecting us back to Week 4. Like Li Po and Tu Fu, Basho rejected urban life and travelled extensively in the country, creating again a mythic sense of the poet as someone who rejects society and retreats into the wilderness.

What is a haiku?

The haiku is a meditative form relating to the natural world, centred on either a contrast or similarity. A seasonal word, phrase or idea (called a kigo) is usually included: something which ties the poem to nature and specifically to the seasons. The haiku consists of a compressed idea or compressed observation – like all poems, it is about saying as much as possible in just a few words.

The essence of haiku is “cutting” (kiru). This is often represented by the juxtaposition of two images or ideas and a kireji(“cutting word”) between them, a kind of verbal punctuation mark which signals the moment of separation and colours the manner in which the juxtaposed elements are related. Traditional haiku consist of 17 on (also known as morae though often loosely translated as “syllables”), in three phrases of 5, 7, and 5 on respectively. On are similar to but differ slightly from syllables. They are the elements of words, which includes each sound of the word, but can also include additional elements which are not sounded – for example, an apostrophe and a s at the end of a possessive would count as a separate on, but not a separate syllable.

In Japanese, haiku are traditionally printed in a single vertical line. The idea of the haiku as consisting of three separate lines, made up of seventeen syllables, is very much a Western interpretation. Even the split into 5, 7 and 5 on is not always kept strictly in Basho. Rather, what matters is the rhetorical sense of the form: the compression of an idea into just a few syllables, and the cut of one idea into another.

Basho’s Haiku

old pond

frog leaping

splash

Translated by Cid Corman

The old pond,

A frog jumps in:

Plop!

Translated by Alan Watts

The old pond

A frog jumped in,

Kerplunk!

Translated by Allen Ginsberg

古池や蛙飛び込む水の音

ふるいけやかわずとびこむみずのおと

(transliterated into 17 hiragana)

furu ike ya kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto

(transliterated into rōmaji)

This separates into on as:

fu-ru-i-ke ya

ka-wa-zu to-bi-ko-mu

mi-zu-no-o-to

This haiku, often called ‘Old Pond’, is Basho’s best-known poem, and indeed is probably the most famous of all haiku. It features a characteristic sense of peace and tranquillity combined with a sense of life, something which the reveals the influence of Zen Buddhism and its tradition of the power of stillness. It also has a particular humour about it – students may find it particularly enjoyable to compare the last lines of each translation! This humour is part and parcel of the poem’s reflectiveness.

the first cold shower

even the monkey seems to want

a little coat of straw

初しぐれ猿も小蓑をほしげ也

はつしぐれさるもこみのをほしげなり

hatsu shigure saru mo komino wo hoshige nari

ha-tsu shi-gu-re

sa-ru mo ko-mi-no wo

ho-shi-ge na-ri

Again we see here how the haiku is a compressed observation, combining humour (the image of the monkey’s ‘little coat of straw’) with reflectiveness, and stillness with life. The ‘first cold shower’ here is a more explicit seasonal reference, but is similar to the leaping of the frog in the first example – it is one of the marker’s of the arrival of spring.

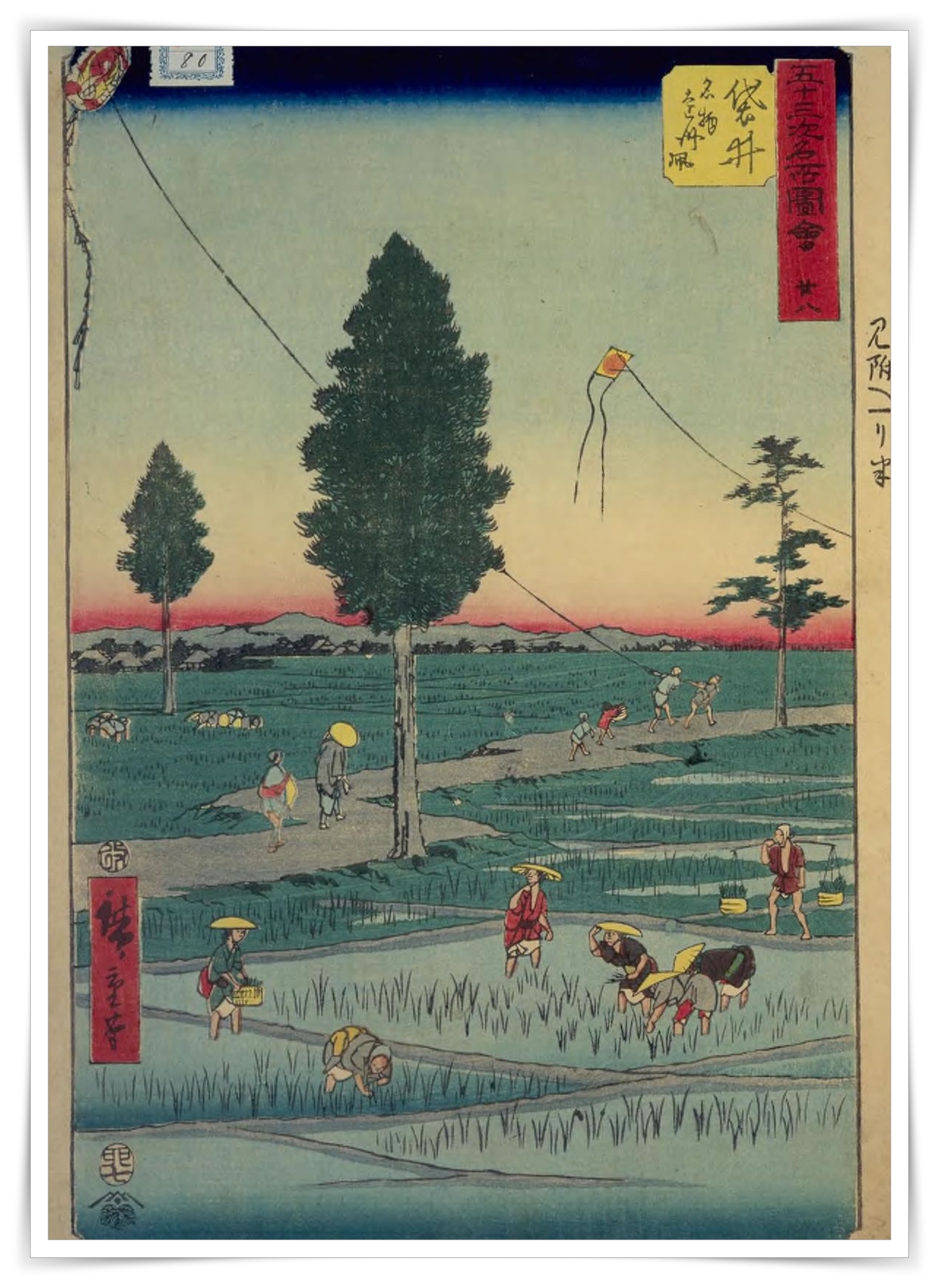

The beginning of art –

The depths of the country

And a rice-planting song.

Summer grasses –

All that remains

Of soldiers’ visions.

Clouds now and then

Giving men relief

From moon-viewing.

The beginning of autumn:

Sea and emerald paddy

Both the same green.

Silent and still: then

Even sinking into the rocks,

The cicada’s screech.

The winds of autumn

Blow: yet still green

The chestnut husks.

You say one word

And lips are chilled

By autumn’s wind.

A flash of lightning:

Into the gloom

Goes the heron’s cry.

Translated by Geoffrey Bownas/Anthony Thwaite

This sequence of haiku provides an opportunity to ask students to identify the various ways in which Basho’s haiku mark the seasons. There is a rice-planting song, summer grasses, the screech of a cicada, autumn wind and chestnut husks. Students should also try and identify the central idea that is being crystallised in each poem – for example, the dynamic of a relationship in the penultimate example, or a striking metaphor for the sound of a heron in the final example. Finally, students can note where the ‘cut’ between two ideas is place in the different haiku – sometimes near the beginning, as in the first, second and last examples, and sometimes later on, as in the third example, where the moon suddenly pokes into the poem as though appearing from behind a cloud.

The Haibun

Haikus were often found as part of a mixed form called the haibun, a new genre combining classical prototypes, Chinese prose genres and vernacular subject matter and language. Traditional haibun typically took the form of a short description of a place, person or object, or a diary of a journey or other series of events in the poet’s life.

Basho was a pioneer of the haibun, and wrote some as travel accounts during his various journeys, the most famous of which is Oku no Hosomichi (Narrow Road to the Deep North).

Bashō’s shorter haibun include compositions devoted to travel and others focusing on character sketches, landscape scenes, anecdotal vignettes and occasional writings written to honor a specific patron or event. His Hut of the Phantom Dwelling can be classified as an essay while, in Saga Nikki (Saga Diary), he documents his day-to-day activities with his disciples on a summer retreat. It is this haibun we will look first at as an example, before turning to the famous Narrow Road to the Deep North.

The Saga Diary

Eighteenth Day (Fourth Moon)

On the eighteenth day of the fourth moon in the fourth year of Genroku, we make an excursion to Saga and arrive at Kyorai’s country house, Fallen Persimmons. Boncho accompanies me. He stays until evening and then returns to Kyoto. I am to stay a little longer. The paper screen doors have been patched, weeds have been pulled, and a room in the corner of the house has been prepared as my bedroom. There is a desk, an inkstone, a writing case, and the following books: Po Chu-i’s collected poems, Chinese Poems by Japanese Poets: One by Each, Tales of Succession, The Tale of Genji, The Tosa Diary, and The Pine Needle Collection. Along with these are various sweets arranged in a set of five gold-lacquered containers, stacked one on top of the other, with pictures painted in the Chinese style, and a bottle of vintage sake with wine cups. The bedding and relishes are brought over from Kyoto and are not lacking in any respect. I forget my previous abstemious existence and enjoy the luxury.

Nineteenth

About the middle of the hour of the horse, we visit Rinsen Temple. The Oi River flows in front of the temple, just to the right of Mount Arashi, and into the village of Matsu-no-o. The coming and going of worshippers to the Bodhissatva Koku is continuous. Amid the bamboo thickets of Matsu-no-o is one of the reputed sites of Lady Kogo’s residence. There are three of these sites in the upper and lower Saga valley. I wonder which one is the real one. Since there is a bridge nearby called Horse-stopping Bridge, where Nakakuni of old is said to have paused with his horse, might it not have been this area? Lady Kogo’s grave is in the bamboo thicket next to the small teahouse. A cherry tree has been planted as the grave marker. She, who spent her daily life in silk-embroideredgarments and quilts, in the end turned into dust and compost among bamboo thickets. I am reminded of the willow of Chao-chun village, the flower of Wunu shrine of the old Chinese legends.

Sad nodes –

we’re all the bamboo’s children

in the end.

Arashi Mountain –

the path of the wind

through the bamboo grove.

We return to the house as the sun begins to sink. Boncho comes from Kyoto. Kyorai returns to Kyoto. I retire early in the evening.

Twentieth

Nun Uko comes to see the festival of North Saga. Kyorai comes from Kyoto. Talks about the following poem, which he says he composed on the way here.

Wrangling children –

they’re all the same height

as the barley.

Fallen Persimmons House is unchanged from the way it was built by the previous owner, but here and there are some damage and decay. The present wretched condition is indeed more appealing to us than its previous polish and refinement. The sculptured beams and painted beams, too, are damaged by winds and soaked by rains; uniquely shaped rocks and pine trees are hidden under weeds. The blossoms of a single potted lime tree in front of the bamboo are fragrant, and they inspired these verses.

Lime blossoms!

let’s talk about the old days

making dinner in the kitchen.

Cuckoo’s cry –

moonlight seeps

through the thicket of bamboo.

We’ll come again,

so ripen, strawberries

of Saga Mountain!

The wife of Kyorai’s older brother sends us some sweets and relishes. This evening Boncho and Uko stay overnight. Since five of us sleep together under one mosquito net, it is difficult to fall asleep, and a little after midnight each of us gets up. Bringing out the sweets and sake cups of this afternoon, we talk until nearly dawn. Last summer when Boncho slept at my house, people from four different provinces slept under a two-mat mosquito net. We all laugh when someone remembers that on that occasion someone said in passing, ‘Four minds, four dreams.’ As morning arrives, Uko and Boncho return to Kyoto. Kyorai stays on.

Here we have an example of how the haibun form worked. ‘The Saga Diary’ consists of prose sections which carefully describe different places, with particular emphasis on the various markers of and connections to the past within those places, interspersed with brief meditations on these observations in the form of the accompanying haiku. The diary is characterised by its very exact descriptions, with lots of specific details: the name of the house (Fallen Persimmons), the patched paper screen doors. This is very much a part of the haibun aesthetic, as are the nods to the civilisations and literatures of the past, such as the mention of the Tale of Genji.

Students should take particular note of how each haiku is drawn out of the experience of the day. The first haiku, for example, mirrors the discussion in the previous paragraph of how an aristocratic figure is buried in the bamboo thickets, with the bamboo growing from the ashes of his body, an idea that is then picked up in the haiku: ‘we’re all bamboos children’. The ghostly feeling is also carried over from the prose section into the poems that follow.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North

The interiors of the two sacred buildings of whose wonders I had often heard with astonishment were at last revealed to me. In the library of sutras were placed the statues of the three nobles who governed this area, and enshrined in the so-called Gold Chapel were the coffins containing their bodies, and three sacred images. These buildings, too, would have perished under the all-devouring grass, their treasures scattered, their jewelled doors broken and their gold pillars crushed, but thanks to the outer frame and a covering of tiles added for protection, they had survived to be a monument of at least a thousand years.

Even the long rain of May

Has left it untouched –

This Gold Chapel

Aglow in the sombre shade.

Turning away from the highroad leading to the provinces of Nambu, I came to the village of Iwate, where I stopped overnight. The next day, I looked at the cape of Oguro and the tiny island of Mizu, both in a river, and arrived by way of Naruko hot spring at the barrier-gate of Shitomae which blocked the entrance to the province of Dewa. The gate-keepers were extremely suspicious, for very few travellers dared to pass this difficult road under normal circumstances. I was admitted after long waiting, so that darkness overtook me while I was climbing a huge mountain. I put up at a gate-keeper’s house which I was very lucky to find in such a lonely place. A storm came upon us and I was held up for three days.

Bitten by fleas and lice,

I slept in a bed,

A horse urinating all the time

Close to my pillow.

(Translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa)

In this haibun we get a strong sense of time passing and of ruin, connecting us right back to the start of the course, to the epic of Gilgamesh. This concern with the past, and with the inevitability of everything falling into ruin, seems to be a continual concern of poets from across history and across the globe – it is one of the great universal themes. Basho here explores this idea by inverting it – the surprise of the poem is that the sacred buildings have survived. Yet there is still a pervading sense that this can only be temporary – note how the entry consists primarily of images of ruin, even as it describes the preserved interiors of the buildings. We also see here the ability of the haibun form to capture the problems of the traveller, catching the small moments of the traveller’s journey in the diary-like structure. Again, students should examine how the haiku emerge out of the diary: how the ‘sombre shade’ for example picks up on the complicated emotional tone of the description of the preserved building. Students can also again be reminded of the fact that the organisation of haiku into three lines is a Western idea, and is not always strictly adhered to, as we see here with the four-line haiku.

Renga

The final form we look at this week is the renga, from which the haiku emerged. The renga is a social, collaborative form, written by more than one poet. Renga, meaning “linked poem,” began over seven hundred years ago in Japan to encourage the collaborative composition of poems. Poets worked in pairs or small groups, taking turns composing the alternating three-line and two-line stanzas. Linked together, renga were often hundreds of lines long, though the favored length was a 36-line form called a kasen. Several centuries after its inception, the opening stanza of renga gave rise to the much shorter haiku.

To create a renga, one poet writes the first stanza, which is three lines long with a total of seventeen syllables. The next poet adds the second stanza, a couplet with seven syllables per line. The third stanza repeats the structure of the first and the fourth repeats the second, alternating in this pattern until the poem’s end.

Thematic elements of renga are perhaps most crucial to the poem’s success. The language is often pastoral, incorporating words and images associated with seasons, nature, and love. In order for the poem to achieve its trajectory, each poet writes a new stanza that leaps from only the stanza preceding it. This leap advances both the thematic movement as well as maintaining the linking component.

A Hundred Stanzas by Three Poets at Minase

Despite some snow

the base of the hills spreads with haze

the twilight scene

Despite some snow

the base of the hills spreads with haze

the twilight scene

where the waters flow afar

the village glows with sweet plumb flowers

Where the waters flow afar

the village glows with sweet plumb flowers

in the river wind

a single stand of willow trees

show spring color

In the river wind

a single stand of willow trees

show spring color

day break comes on distinctly

with sounds of punted boat”

. . . and so on . . .

Here students can examine how this worked in practice. We see here an abundance of natural and seasonal language: snow spread on the hills, sweet plumb flowers, the river wind, willow trees. We also see how each stanza leaps out of the previous one, repeating it and then building from it into a new idea. This leaping also often has the suggestion of a seasonal movement: from the snow of winter to the flowers of spring, for example. Students can discuss the effects of the linked form, and also consider how the different haiku contained within the renga might be read differently if they were read in isolation. Note, too, that the second, five-line stanza also has a name – the tanka – and, like the haiku, became a form in its own right. The tanka consists of a haiku followed by a couplet.

Tasks

One

Ask students to experiment with the haibun form, creating a travel diary – perhaps of their journey to or from class – and then capturing individual moments from that diary in the form of their own haiku. The focus here should be on playing with the relationship between the haiku and the prose diary entries. Students should also try to replicate the haiku form’s distinctive ‘cut’ between two ideas in the haiku sections of their haibuns.

Two

Write a renga as a class, with each student continuing the poem as in the process described above. This is a particularly nice way of finishing the course, as it involves the whole class writing a poem together. Below are some examples from Tim Dooley’s previous poetry workshops of students having done this:

Renga 1

A single gull shrieks.

Ill-slept I tumble into

the bright shock of day.

Rich red sun over the downs –

fishing boats bounce on the waves.

A wash. Cold tide turns.

The dream’s recalled – bare nets hauled.

Anchor rode flailing.

Feet feel for slippers. The fish

I chased is swimming away.

Water keeps its print –

barred muscle for a moment –

then pours in, dissolves.

My bed is now glass-bottomed;

in the ooze, dreams swim like clouds.

The deep, a loosened

maze of harbour, bank and beech

drifting in the dark,

reflects the scattered starlight

trawled from slowly-lifting waves.

The fisherman’s face lights up

as the pebbles were washed up.

Every dawn has a story under its wings.

In first gold they open, lift,

made new by night-tears to speak.

Crossing to the window,

dreams fall off like clear water.

Light comes from the bay,

like steam comes off a coffee

held by someone you might love,

but will not speak to

until, together, you have

bowed your heads and sipped

from the bowl of common purpose

a quiet rhythmic voice.

(Ömer Askoy, Tom Baker, Simon Bowden, Marie-Elsa Bragg, Annie Crozier, Ruthb Davis, Tim Dooley, Clare Finney, Alice Hiller, Tim Jones, Tommy Karshan, Ann Perrin and John White)

Renga 2

I sweep yellow leaves

a gust of wind tosses them

I must sweep again

to make way for winter’s coming.

In the snow a fresh footprint,

the child’s bright, brown eyes

now stare into mine, amazed

at such foolishness.

The moon agrees, sure as the

pale curve of its fingernail.

The stars are blinking

as if in joyous agreement

with the child’s question.

The child will hold petals long

after snows have melted and gone,

petals which may fall

in the hair of a stranger

his first summer love

delightful, delicate, destined

to fade in autumn’s decay.

(George Appleby, Angela Bailey, Annie Crozier, Tim Dooley, Anuradha Gupta, Molly Janz, Roy Mcfarlane, Tushita Ranchan, Lesley Sharpe)

The End

We have arrived at the end of the course! To close, it might be beneficial to ask students what they have learned, what techniques they would like to adapt for their own poetry going forward, and which poetic forms they have been most attracted to. If time, it would also be good to discuss the themes and connections that have emerged between different weeks of the course, across different historical eras and geographical locations. For example, among other things, you might like to touch on: the idea of the poet as an outsider; poetry’s relationship with the past and the ideas of ruin and loss; the continual attraction of poets to natural imagery and language; poetry’s relationships to love, politics and morality; and, perhaps above all else, the ways in which different poetic forms create different ways of looking at the world. Finally, it would be worth discussing what continuities (and discontinuities) exist between the poetry of past civilizations and our present situation.

We hope this course has been a useful resource for your teaching. If you’d like to get in touch, particularly about your experiences using these materials to teach, please send a message here.