Introduction

This week looks at the development of Irish poetry, finding in its particular traditions a number of poetic practices and ways of working which modern students can adapt to their own poetry-writing. It begins with another insight into how the practice of poetry has been shaped by the circumstances of its composition: the development of Irish poetry in the margins of Latin texts copied out by scribes.

Irish learning took on a particular force with the decline of the Roman empire. Ireland was unique in that it was Christianised but not fully Romanised – it was never part of the Roman empire. Rather, it was converted to Christianity by British Christians at the turn of the 6th century. During that time, an Irish monastic system was set up, which helped preserve Latin texts. In the 7th and 8th centuries this developed further, as scribes began work on restoring these texts, copying them out to further preserve them.

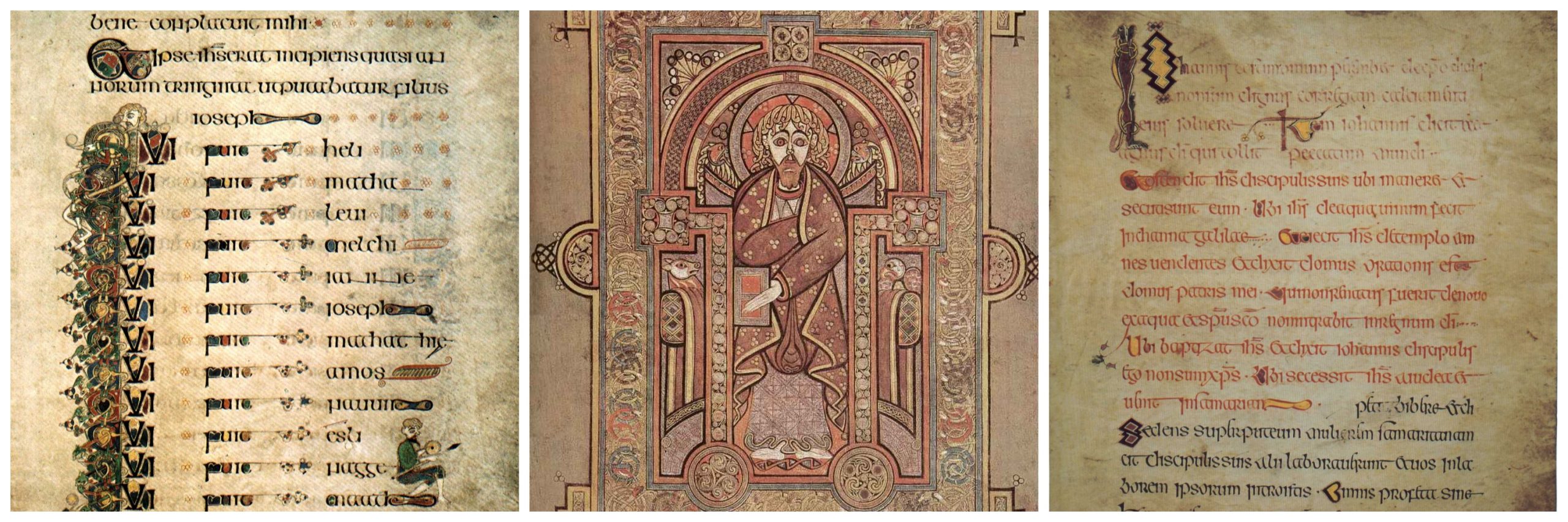

The Irish scribes brought new various elements to the writing of manuscripts. They were the first manuscript writers to put gaps between their words, something previously not done as parchment was too expensive. They also showed great innovation and skill in their decoration of the manuscripts, as can be seen, for example, in the Book of Kells. (See images above).

The most important innovation for our purpose, though, was that they began adding their own poems, in their own language, in the margins of the texts they were copying out. Students can see how this looked by examining the Irish Priscian manuscript of St. Gallen, where both the Latin text and the glosses in Old Irish can be seen. Thus began the tradition of Irish poetry – a poetry of marginalia.

The Scribe in the Woods

Original (9th century)

Dom-farcai fidbaide fál

fom-chain loíd luin, lúad nád cél;

h-úas mo lebrán, ind línech,

fom-chain trírech inna n-én.

Fomm-chain coí menn, medair mass,

hi m-brot glass de dingnaib doss.

Debrath! nom-Choimmdiu-coíma:

caín-scríbaimm fo roída ross

Tr. Ciaran Carson

all around me greenwood trees

I hear blackbird verse on high

quavering lines on vellum leaves

birdsong pours down from the sky over and above the wood

the blue cuckoo chants to me

dear Lord thank you for your word

I write well beneath the trees

Tr. Whitley Stokes and John Strachan, 1903

A hedge of trees surrounds me: a blackbird’s lay sings to me – praise which I will not hide –

above my booklet the lined one trilling of the birds sings to me.

In a gray mantle the cuckoo’s beautiful chant sings to me from the tops of bushes:

may the Lord protect me from Doom! I write well under the greenwood.

Tr. Maire Mac Neill

Over me green branches hang

A blackbird leads the loud song

Above my pen-lined booklet

I hear a fluting bird-throng

The cuckoo pipes a clear call

Its dun cloak hid in deep dell:

Praise to God for his goodness

That in woodland I write well

To begin to get students to understand how this practice of scribing shaped the poetry itself, here is a 9th century poem, ‘The Scribe in the Woods’, along with three different translations.

First draw the students’ attention to what can be noticed in the Irish original, even for those who don’t speak Irish. Students can see that the poem is alliterative and uses assonance: fom-chain loíd luin, lúad nád cél. They can also identify the use of half-rhyme (fál/cél, mass/doss), something which continues into much later Irish poetry, such as Yeats and Muldoon.

Then discuss the three contemporary translations of the poem. The poet writes of his observations of nature, linking art and spirituality (the subjects of his scribe-work) with what he observes around him in nature, focussing particularly on the birds. There is a degree of self-reference, in the connection of the lines of the manuscript with the ‘quavering lines’ of blackbird verse. A sense is given of the blackbird as a musician and the scribe as recording their song. Poetry here is a vernacular, secular art which is written in a sacred context. The poet makes a space for the individual in among the eternal world of the scripture.

Pangur Bán

The Scholar and his Cat (c. 800)

Messe ocus Pangur Bán,

cechtar nathar fri saindán:

bíth a menma-sam fri seilgg,

mu menma céin im saincheirdd

Caraim-se fos, ferr cach clú,

oc mu lebrán, léir ingnu;

ní foirmtech frimm Pangur Bán:

caraid cesin a maccdán.

Ó ru biam, scél cen scís,

innar tegdais, ar n-óendís,

táithiunn, díchríchide clius,

ní fris tarddam ar n-áthius.

Gnáth, h-úaraib, ar gressaib gal

glenaid luch inna línsam;

os mé, du-fuit im lín chéin

dliged n-doraid cu n-dronchéill.

Fúaichaid-sem fri frega fál

a rosc, a n-glése comlán;

fúachimm chéin fri fégi fis

mu rosc réil, cesu imdis.

Fáelid-sem cu n-déne dul

i n-glen luch inna gérchrub;

hi tucu cheist n-doraid n-dil

os mé chene am fáelid.

ia beimmi a-min nach ré

í derban cách a chéle:

aith la cechtar nár a dán;

ubaigthius a óenurán.

h-É fesin as choimsid dáu

in muid du-ngní cach óenláu;

du thabairt doraid du glé

for mo mud céin am messe.

From the Irish of Pangur Ban (Eavan Boland)

Myself and Pangur, cat and sage

Go each about our business;

I harass my beloved page,

He his mouse.

Fame comes second to the peace

Of study, a still day

Unenvying, Pangur’s choice

Is child’s play.

Neither bored, both hone

At home a separate skill

Moving after hours alone

To the kill

When at last his net wraps

After a sly fight

Around a mouse; mine traps

Sudden insight.

On my cell wall here,

His sight fixes, burning,

Searching; my old eyes peer

At new learning,

And his delight when his claws

Close on his prey

Equals mine when sudden clues

Light my way.

So we find by degrees

Peace in solitude,

Both of us, solitaries,

Have each the trade

He loves: Pangur, never idle

Day or night

Hunts mice; I hunt each riddle

From dark to light.

Myself and Pangur (Paul Muldoon)

Myself and Pangur, my white cat,

have much the same calling, in that

much as Pangur goes after mice

I go hunting for the precise

word. He and I are much the same

in that I’m gladly ‘lost to fame’

when on the Georgics, say, I’m bent

while he seems perfectly content

with his lot. Life in the cloister

can’t possibly lose its lustre

so long as there’s some crucial point

with which we might by leaps and bounds

yet grapple, into which yet sink

our teeth. The bold Pangur will think

through mouse-snagging much as I muse

on something naggingly abstruse,

then fix his clear, unflinching eye

on our lime-white cell wall, while I

focus, in so far as I can,

on the limits of what a man

may know. Something of his rapture

at his most recent mouse-capture

I share when I, too, get to grips

with what has given me the slip.

And so we while away our whiles,

never cramping each other’s styles

but practising the noble arts

that so lift and lighten our hearts,

Pangur going in for the kill

with all his customary skill

while I, sharp-witted, swift and sure,

shed light on what had seemed obscure.

Version by W.H. Auden

Pangur, white Pangur, How happy we are

Alone together, scholar and cat

Each has his own work to do daily;

For you it is hunting, for me study.

Your shining eye watches the wall;

My feeble eye is fixed on a book.

You rejoice, when your claws entrap a mouse;

I rejoice when my mind fathoms a problem.

Pleased with his own art, neither hinders the other;

Thus we live ever without tedium and envy.

Version by Seamus Heaney

Pangur Bán and I at work,

Adepts, equals, cat and clerk:

His whole instinct is to hunt,

Mine to free the meaning pent.

More than loud acclaim, I love

Books, silence, thought, my alcove.

Happy for me, Pangur Bán

Child-plays round some mouse’s den.

Truth to tell, just being here,

Housed alone, housed together,

Adds up to its own reward:

Concentration, stealthy art.

Next thing an unwary mouse

Bares his flank: Pangur pounces.

Next thing lines that held and held

Meaning back begin to yield.

All the while, his round bright eye

Fixes on the wall, while I

Focus my less piercing gaze

On the challenge of the page.

With his unsheathed, perfect nails

Pangur springs, exults and kills.

When the longed-for, difficult

Answers come, I too exult.

So it goes. To each his own.

No vying. No vexation.

Taking pleasure, taking pains,

Kindred spirits, veterans.

Day and night, soft purr, soft pad,

Pangur Bán has learned his trade.

Day and night, my own hard work

Solves the cruxes, makes a mark.

Translator’s Notes: Pangur Bán by Seamus Heaney

This poem, found in a ninth-century manuscript belonging to the monastery of St. Paul in Carinthia (southern Austria), was written in Irish and has often been translated. For many years I have known by heart Robin Flower’s version, which keeps the rhymed and endstopped movement of the seven-syllable lines, but changes the packed, donnis/monkish style of the original into something more like a children’s poem, employing an idiom at once wily and wilfully faux-naif: “I and Pangur Bán, my cat,/’Tis a like task we are at…,” “’Tis a merry thing to see/At our tasks how glad are we/When we sit at home and find/Entertainment for our mind,” and so on.

Sometimes known as “Pangur Bán” (“white pangur”—“pangur” being an old spelling of the Welsh word for “fuller,” the man who works with white fuller’s earth), sometimes known as “The Scholar/Monk and his Cat,” the poem pads naturally out of Irish into the big-cat English of “The Tyger.” And since Blake’s meter acted as Flower’s tuning fork, and as Yeats’s when Yeats came to write his exhortations to Irish poets, I was glad to “keep the accent” and thereby instate the author of “Pangur Bán” at the head of the line of those Irish poets who are meant to have “learned their trade.”

Like many other early Irish lyrics—“The Blackbird of Belfast Lough,” “The Scribe in the Woods,” and various “season songs” by the hermit poets—“Pangur Bán” is a poem that Irish writers like to try their hand at, not in order to outdo the previous versions, but simply to get a more exact and intimate grip on the canonical goods. Nevertheless, had it not been for the editor’s invitation to contribute to this issue, it’s unlikely that I would ever have made bold to face the job: the tune of the Flower version is ineradicably lodged in my ear, and I just assumed that for me “Pangur Bán” would always be a no-go area.

A hangover helped. Not so much “tamed by Miltown” as dulled by Jameson, I applied myself to the glossary and parallel text in the most recent edition of Gerard Murphy’s Early Irish Lyrics (Four Courts Press, 1998) and was happy to find that I had enough Irish and enough insulation (thanks to Murphy’s prose and whiskey’s punch) to get started.

In this famous Irish poem the scribe writes about his cat. Again, begin by drawing students’ attention to what they can surmise from the original Irish language version. By reading the poem aloud, even without understanding its meaning, students can detect the four-beat line, with roughly seven syllables per line. Again there is assonance rather than full rhyme, with similar vowels in couplets but not always the same final consonant.

Then compare the different translations of the poem. Auden’s version has a sense of balance, with its use of parallelism, as well as an epigrammatic quality given to it. Heaney keeps closer to the original sense of the rhythm, with a seven-syllable line: a cataleptic trochaic tetrameter, like Blake’s famous ‘The Tyger’. (He also hints, in the phrase ‘learned their trace’, at Yeats’s poem ‘Under Ben Bulben’, which again uses this same rhythm.) Boland keeps again this seven-syllable line, but has a different stanza shape, with a shorter fourth line of only three syllables. Muldoon, meanwhile, has a more sing-songy eight syllable line, and, unusually for Muldoon, is fairly full in his rhyme scheme, avoiding the odd assonances and half rhymes that normally characterise his poetry. As well as comparing the different metrical and formal decisions each translator has made, students can compare how, in each version, hunting and composition are brought together and compared as equivalent acts.

The Blackbird by Belfast Loch

The Blackbird by Belfast Loch (9th century)

Int én bec

ro léic feit

do rinn guip

glanbuidi:

fo-ceird faíd

ós Loch Laíg,

lon do chraíb

charnbuidi.

The Blackbird of Belfast Loch (Seamus Heaney)

The small bird

Chirp-chirruped:

Yellow neb,

A note spurt.

Blackbird over

Lagan water,

Clumps of yellow

Whin-burst!

The Bangor Blackbird (Derek Mahon)

Just audible over the waves

a blackbird among leaves

whistling to the bleak

lough from its whin beak.

The Blackbird of Belfast Loch (Ciaran Carson)

The little bird

that whistled shrill

from the nib of

its yellow bill a note let go

o’er Belfast Lough—

a blackbird from

a yellow whin

To draw out both the different metrical approaches to translation, and the continual comparison in Irish poetry between the process of writing and the natural world, students can compare different translations of this 9th century poem about a blackbird. The very short three-syllable line is kept by Heaney, turned into couplets by Muldoon, and turned into two quatrains by Carson. What are the different effects of these metrical decisions?

Students, too, should note the use of dialect words, another hallmark of Irish lyric. The poem, which is situated in a Belfast loch, makes use of words like “neb” for beak and “whin” for gorse. The beak of the blackbird is compared to a pen, called a “nib” by Carson in a play on Heaney’s “neb”. As in the ‘The Scribe in the Woods’, there is a connection between birds and poets as song-makers.

As a final exercise, students can compare the many (perhaps unexpected) similarities between the Irish poems they’ve been looking at this week and the Tang dynasty poetry of last week. In both there is a focus on the isolated image, as well as sense of the poet as someone who has stepped away from responsibility, withdrawn from the world into an area of private thought. This sense of writing at one side of the world of work is interesting to compare to the development of Irish lyric as a form of marginalia.

Tasks

One (the vocation and the avocation)

Write a poem which is seen as a break from other work, or which is turned away from a more work-like activity. This could mean asking students to find a time in their work lives when they can write a poem, which they can then bring to next week’s class.

Two (other lives)

Write a poem which looks to other forms of life and attends to them, empathising or identifying with them: for example, a poem imagining the life of a cat or a bird. This can be combined with the above task – for example, turning away from the world of work and watching a bird out of the window, as the scribe does in the first Irish poem above.

Three (the scribe)

Get students to try copying out a text and writing a poem at the same time, during the act of inscription, in the margins. What effect does this have on their process of composition? How do the two forms of ‘writing’, occurring simultaneously, affect each other?

Four (major, minor)

Ask students to choose a text which is seen as a ‘major work’ and write something which might be seen as ‘working away from it’ towards a ‘minor’ work – exploring that consciousness of ‘minor’ and ‘major’.

Further Reading

John Keats’s ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’ – a famous example of poem which grows out of a ‘major’ work, in the margins of it so to speak.

Basil Bunting’s ‘On the Fly-Leaf of Pound’s Cantos’ – another poem written in the shadow of another, this time literally on the same page, similar to the Irish scribes’ marginalia.