Introduction

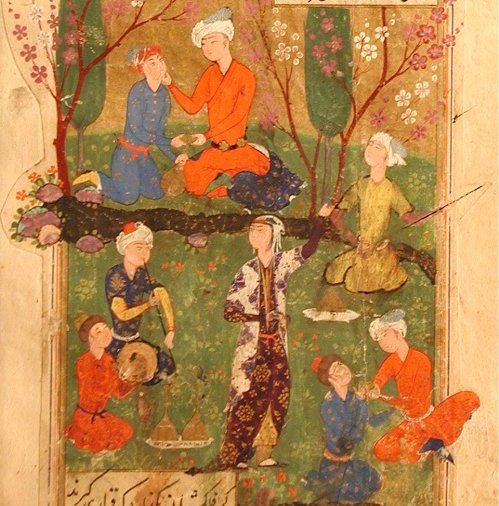

This week looks at the Persian poet Hafiz (also transliterated as Hafez) and the poetic form of the ghazal which he mastered. Hafiz’s was a lyrical poetry, with his ghazals often celebrating love or expressing feelings of loss. He was born in Shiraz, Iran, where he lived and wrote – the same Shiraz from which the wine grape comes. Indeed, the culture of Shiraz was one of wine-drinking, mysticism and pleasure, with Hafiz’s poetry expressing ideas of ecstasy and freedom from restraint. He was also a Sufi Muslim, a branch of Islam interested in artistic expression, music and dance.

For students, one of the key aspects of the ghazal which this week focusses on drawing out it is serial nature. The couplets in a ghazal link together like beads in a chain, with each couplet having a quality in itself as an image. Perhaps the other defining feature is the inclusion of the name of the poet in the final couplet, either explicitly or sometimes half-hidden in a pun, as a kind of ‘signing off’ of the poem.

What is a Ghazal?

The ghazal is less well-known in the West than, say, the sonnet, limerick or sestina, so it may be worth beginning the class by explaining the background and basic formal features of this particular poetic tradition.

The ghazal is a poetic form consisting of rhyming couplets and a refrain, with each line sharing the same meter. A ghazal may be understood as a poetic expression of both the pain of loss or separation and the beauty of love in spite of that pain. Ghazal (pronounced ‘ghuzzle’) is an Arabic word meaning ‘talking to women’. The form is ancient, originating in Arabic poetry and developing in 10th Century Persia, where it was derived from the Arabian qasida. It was then brought to India with the Mogul invasion in the 12th century. Ghazals were written by Rumi and Hafiz of Persia; the Azeri poet Fuzûlî in the Ottoman Empire; Mirza Ghalib and Muhammad Iqbal of North India; and Kazi Nazrul Islam of Bengal. Through the influence of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), the ghazal became very popular in Germany during the 19th century.

A traditional ghazal consists of five to fifteen couplets, typically seven. A refrain (a repeated word or phrase) appears at the end of both lines of the first couplet and at the end of the second line in each succeeding couplet. In addition, one or more words before the refrain are rhymes or partial rhymes. The lines should be of approximately the same length and meter. The poet may use the final couplet as a signature couplet, using his or her name in first, second or third person, and giving a more direct declaration of thought or feeling to the reader.

Each couplet should be a poem in itself, like a pearl in a necklace. There should not be continuous development of a subject from one couplet to the next through the poem. The refrain provides a link among the couplets, but they should be detachable, quotable, grammatical units. There should be an epigrammatic terseness, yet each couplet should be lyric and evocative.

Hafiz’s Ghazals

We begin by looking at some of Hafiz’s own ghazals, focussing in the first on the content of the poem, and in the second on its form.

Ghazal 85

We couldn’t taste his lips before he left.

His light-filled moon face shone no more. He left. Perhaps, you say, he felt constrained by us.

He broke his chains alone before he left. We chanted Suras, said so many prayers …

We spoke the heart’s language before he left. His gaze said, “I will never leave desire.”

We held his gaze in our mirror. He left. He walked into the meadow full of love.

We’d never felt such spirit before he left. By weeping when he’s gone we’re like Hafez.

Our goodbye kept us here before he left.

Hafez translated from the Farsi by Roger Sedarat

Ghazal 85 is infused with a sense of loss, of somebody having disappeared. The world of desire and the world of religion are intertwined. The poem has homoerotic overtones – “we couldn’t taste his lips” – mingled with imagery from religion, such as the chanted Suras and prayers. Hafiz often played with mixing bodily pleasure and religion in this way; his name literally means someone who keeps or treasures the Qu’ran, and he was himself a Muslim, yet his verse often plays on this idea of devoutness.

Ghazal 84

Dear wine boy, bring us wine. The fast’s over.

Give us the cup. The well-known past’s over. It’s time to say prayers we’ve long forgotten.

Thank God the break from wine at last’s over. Intoxicate me so I will forget

Those I’ve known well and those I’ve passed over. We catch the scent of what’s inside the cup.

We send, in thanks, our deepest prayers over. From the dead heart new life had reached the soul.

From the soft breeze your perfume passed over. The prideful ascetic followed danger.

The path to a safe life’s been passed over. I spent all my heart’s currency on wine.

My counterfeit coins have been passed over. How long can one repent in such turmoil?

Pour wine, at last the madness is over. Don’t try to lead Hafez down the hard path.

He’s discovered wine. The hard path’s over.

Hafez translated from the Farsi by Roger Sedarat

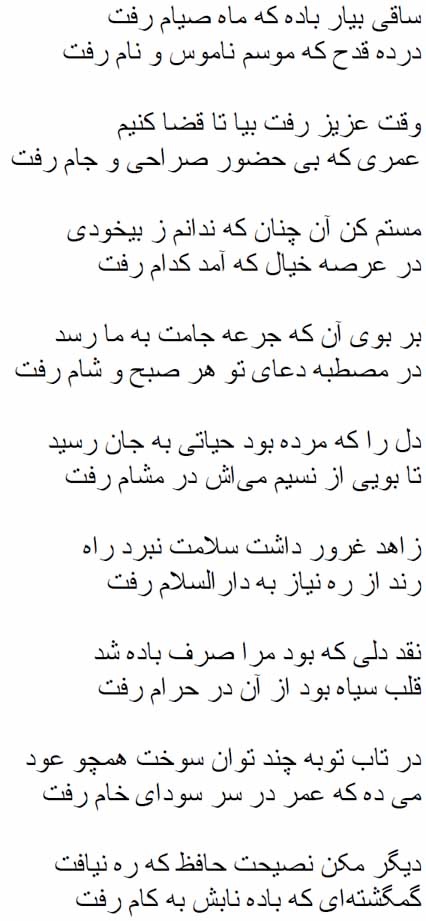

This poem, about the end of a fast, shows well one of the distinctive formal features of the ghazal: the use of a ringing end-rhyme in tandem with a refrain: ‘past’s over’, ‘passed over’, ‘path’s over’ etc. Students can see this too in the Farsi version, the original Arabic script, by carefully examining the characters: remind them that it is read right to left!

This emphasis on the ringing ends of the lines is reflected further in the way that Hafiz’s collection of ghazals, The Divan, is arranged: the poems are ordered alphabetically by the last character in the line.

Mimi Khalvati

Mimi Khalvati is an Iranian-born British poet who has both translated and written her own ghazals. She uses the ghazal form to write about today’s situations.

Ghazal (After Hafez)

However large earth’s garden, mine’s enough.

One rose and the shade of a vine’s enough. I don’t want more wealth, I don’t need more dross.

The grape has its bloom and it shines enough. Why ask for the moon? The moon’s in your cup,

a beggar, a tramp, for whom wine’s enough. Look at the stream as it winds out of sight.

One glance, one glimpse of a chine’s enough. Like the sun in bazaars, streaming in shafts,

any slant on the grand design’s enough. When you’re here, my love, what more could I want?

Just mentioning love in a line’s enough. Heaven can wait. To have found, heaven knows,

a bed and a roof so divine’s enough. I’ve no grounds for complaint. As Hafez says,

isn’t a ghazal that he signs enough?

Khalvati here shows the technique of having a rhyme before a refrain very clearly: ‘vine’s enough’, ‘shines enough’, wine’s enough’, ‘chine’s enough’. (Note: the chine is a word for a mountain ridge used in the South of England, including the Isle of Wight where Khalvati is from.) The sense of musicality that comes across here is very much part of the ghazal tradition and heritage – it is a poetry which longs to be chanted or sung. A lot of Bollywood songs were originally ghazals, for example; we also see the technique of rhyming on the penultimate word being adapted to hip-hop.

Ghazal: To Hold Me

I want to be held. I want somebody near to hold me

when the axe falls, time is called, strangers appear to hold me. I want all that has been denied me. And more.

Much more than God in some lonely stratosphere to hold me. I want hand and eye, sweet roving things, and land

for grazing, praising, and the last pioneer to hold me. I want my ship to come in, crossing the bar,

before my back’s so bowed even children fear to hold me. I want to die being held, hearing my name thrown,

thrown like a rope from a very old pier to hold me. I want to catch the last echoes, reel them in

like a curing-song in the creel of my ear

to hold me. I want Rodolfo to sing, flooding the gods,

Ah, Mimi! as if I were her and he, here, to hold me.

‘To Hold Me’ shows the play with identity and especially with names that is another aspect of the ghazal tradition which many modern interpreters enjoy playing with. The poet’s name lends itself to puns: she uses ‘me, me’ in some of her other ghazals for example. Ask students to think about what they might be able to do with their own names, how they might be able to play with them.

We also see here how Khalvati brings in European elements, such as the reference to Rodolfo from Puccini’s La Bohème (the poet character, whose lover in the opera is the seamstress Mimi, who shares her name with the actual poet Mimi Khalvati!) and the allusion to Tennyson (‘crossing the bar’, the title of a Tennyson poem; note that Tennyson also wrote ghazals and had connections with the Isle of Wight). These European references bring the ghazal out from its Iranian origins and into a new context, transforming it in the process.

Zeina Hashem Beck

Hashem Beck is Lebanese poet who lives in the U.S.A. Whereas Khalvati’s work brings the ghazal into a European tradition of love poetry, Hashem Beck often wields the ghazal for political purposes, as we see in the following poems.

Ghazal: Back Home

For Syria, September 2015

Tonight a little boy couldn’t walk on water or row back home.

The sea turned its old face away. Again, there was a no, no, back home. Bohr is how we were taught to measure poetry,

bohr is how we’ve stopped trying to measure sorrow, back home. ‘All that blue is the sea, and it gives life, gives life,’ says God to the boy

standing wet at heaven’s gate – docs he want to return, to go back home? My friend who hates cooking has made that eggplant dish,

says nothing was better than yogurt and garlic and tomato, back home. On the train tracks, a man shouts, ‘Hold me, hold me,’ to his wife,

bites her sleeve, as if he were trying to tow back home. Thirteen-year-old Kinan with the big eyes says, ‘We don’t want to stay in Europe

Just stop the war,’ he repeats, as if praying, Grow, grow back, home. Habibi, I never thought our children would write HELP US on cardboard.

Let’s try to remember how we met years ago, back home. On our honeymoon we kissed by the sea, watched it

rock the lights, the fishing boats to and fro, back home.

The title of ‘Back Home’, which is also its refrain (‘sorrow back home’, ‘no, no back home’, ‘to go back home’) plays on the poet’s name, Hashem Beck. It is a strong refrain, with its two monosyllables, asserting itself at the end of each couplet and stopping the natural flow of the lines, mirroring the refugees struggles to escape, how they keep coming up against literal and figurative road blocks. The poet mixes shocking and romantic images: heaven’s gate and the blue sea jar against the bitten sleeve and cardboard signs. We also see Hashem Beck’s technique here of bringing in Arabic words, such as habibi (‘beloved’), into her poems, which are sometimes included in Arabic lettering.

Ghazal: With Prayer

The herons were no longer safe in the sky. They flew with prayer,

then fell to us. We hid them from the cats. What to do with prayer? Decades after the civil war, we enter the sniper’s hole, sew

the sandbags, read words for his boyfriend on the wall, true with prayer. Write my name & invite me to a wedding. I want a parade

of cars with flashers on, each blinking red, two times two with prayer. Dear Eurydice, what good a heart that can’t resist looking back?

Foolish, music-laden Orpheus. Almost saved you with prayer. In the museum of memory, the missing accumulate.

They shoot out of the tiles like grass blades, damp & new with prayer. I found a photo in a library book: lovers holding hands.

I felt chosen, then lost it. & I didn’t pursue with prayer. When I interviewed God, I said I moved the plants toward the light,

forgot the water. Is love a lack, always imbued with prayer? Tarot cards, make me beautiful. Abundance me, O Three of Cups,

spin luck O Wheel of Fortune, I’m through, I’m through, I’m through with prayer.

Like Khalvati does in ‘Ghazal: To Hold Me’, we see Hashem Beck here bringing the ghazal into a wider context, drawing in references to Greek mythology, the tarot pack and astrology. The poem is full of different kinds of danger, with the poet coming to the conclusion at the end that prayer is an insufficient response to that danger: ‘I’m through, I’m through, I’m through with prayer’.

Zeina Hashem Beck

Hashem Beck is Lebanese poet who lives in the U.S.A. Whereas Khalvati’s work brings the ghazal into a European tradition of love poetry, Hashem Beck often wields the ghazal for political purposes, as we see in the following poems.

Ghazal: Back Home

For Syria, September 2015

Tonight a little boy couldn’t walk on water or row back home.

The sea turned its old face away. Again, there was a no, no, back home. Bohr is how we were taught to measure poetry,

bohr is how we’ve stopped trying to measure sorrow, back home. ‘All that blue is the sea, and it gives life, gives life,’ says God to the boy

standing wet at heaven’s gate – docs he want to return, to go back home? My friend who hates cooking has made that eggplant dish,

says nothing was better than yogurt and garlic and tomato, back home. On the train tracks, a man shouts, ‘Hold me, hold me,’ to his wife,

bites her sleeve, as if he were trying to tow back home. Thirteen-year-old Kinan with the big eyes says, ‘We don’t want to stay in Europe

Just stop the war,’ he repeats, as if praying, Grow, grow back, home. Habibi, I never thought our children would write HELP US on cardboard.

Let’s try to remember how we met years ago, back home. On our honeymoon we kissed by the sea, watched it

rock the lights, the fishing boats to and fro, back home.

The title of ‘Back Home’, which is also its refrain (‘sorrow back home’, ‘no, no back home’, ‘to go back home’) plays on the poet’s name, Hashem Beck. It is a strong refrain, with its two monosyllables, asserting itself at the end of each couplet and stopping the natural flow of the lines, mirroring the refugees struggles to escape, how they keep coming up against literal and figurative road blocks. The poet mixes shocking and romantic images: heaven’s gate and the blue sea jar against the bitten sleeve and cardboard signs. We also see Hashem Beck’s technique here of bringing in Arabic words, such as habibi (‘beloved’), into her poems, which are sometimes included in Arabic lettering.

Ghazal: With Prayer

The herons were no longer safe in the sky. They flew with prayer,

then fell to us. We hid them from the cats. What to do with prayer? Decades after the civil war, we enter the sniper’s hole, sew

the sandbags, read words for his boyfriend on the wall, true with prayer. Write my name & invite me to a wedding. I want a parade

of cars with flashers on, each blinking red, two times two with prayer. Dear Eurydice, what good a heart that can’t resist looking back?

Foolish, music-laden Orpheus. Almost saved you with prayer. In the museum of memory, the missing accumulate.

They shoot out of the tiles like grass blades, damp & new with prayer. I found a photo in a library book: lovers holding hands.

I felt chosen, then lost it. & I didn’t pursue with prayer. When I interviewed God, I said I moved the plants toward the light,

forgot the water. Is love a lack, always imbued with prayer? Tarot cards, make me beautiful. Abundance me, O Three of Cups,

spin luck O Wheel of Fortune, I’m through, I’m through, I’m through with prayer.

Like Khalvati does in ‘Ghazal: To Hold Me’, we see Hashem Beck here bringing the ghazal into a wider context, drawing in references to Greek mythology, the tarot pack and astrology. The poem is full of different kinds of danger, with the poet coming to the conclusion at the end that prayer is an insufficient response to that danger: ‘I’m through, I’m through, I’m through with prayer’.

Goethe and Lorca

How then did the ghazal travel from ancient Iran to become a popular modern form? The last third of this week’s course traces the missing links…

To Hafiz

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

HAFIZ, thy equal e’er to be

Were dream insane!

A bark drives onward fast and free O’er the tossed main;

She feels her sail swell joyously

,

Rides proud and bold ;

Does Ocean will to rend her, she Rots as she’s rolled.

In songs, how light, how swift, for thee Cool waters flow ;

They leap in waves of fire, but me The o’ermastering glow

Engulphs. Yet bring I one proud plea, Bold, unreproved

I in a sun-bright land, like thee

Have lived and loved.

(Translated by Edward Dowden)

‘To Hafiz’ is taken from the West-East Divan, a long collection of poems by Goethe which were inspired by Hafiz, and meditated on the relationship between the East and West, the Occident and Orient. Goethe here is taking up the name of the Hafiz’s collection and writing his own east-meets-west version, with a very Romanticised, Orientalised view of the Arabic world. (Note that the name was also the inspiration for the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, founded by Edward Said and conductor Daniel Barenboim, which brings together Palestinian and Israeli musicians.)

The poem ‘To Hafiz’ keeps the rhyme scheme of the ghazal form but loses many of the other aspects we have been looking at: the sense of each couplet having itss own meaning like a bead in a chain; the ringing rhyme followed by a refrain; the signiature of the poet in the final couplet; indeed, the final couplet itself. Students can discuss to what extent this poem can be considered a ghazal, and how loose one can be in adapting a poetic form before one is writing a different kind of poem altogether.

Gacela of the Dark Death

Federico García Lorca I want to sleep the sleep of the apples,

I want to get far away from the busyness of the cemeteries.

I want to sleep the sleep of that child

who longed to cut his heart open far out at sea. I don’t want them to tell me again how the corpse keeps all its blood,

how the decaying mouth goes on begging for water.

I’d rather not hear about the torture sessions the grass arranges for

nor about how the moon does all its work before dawn

with its snakelike nose. I want to sleep for half a second,

a second, a minute, a century,

but I want everyone to know that I am still alive,

that I have a golden manger inside my lips,

that I am the little friend of the west wind,

that I am the elephantine shadow of my own tears. When it’s dawn just throw some sort of cloth over me

because I know dawn will toss fistfuls of ants at me,

and pour a little hard water over my shoes

so that the scorpion claws of the dawn will slip off. Because I want to sleep the sleep of the apples,

and learn a mournful song that will clean all earth away from me,

because I want to live with that shadowy child

who longed to cut his heart open far out at sea.

(Translated by Robert Bly)

Gacela de la muerte oscura

Federico García Lorca Quiero dormir el sueño de las manzanas

alejarme del tumulto de los cementerios.

Quiero dormir el sueño de aquel niño

que quería cortarse el corazón en alta mar. No quiero que me repitan que los muertos no pierden la sangre;

que la boca podrida sigue pidiendo agua.

No quiero enterarme de los martirios que da la hierba,

ni de la luna con boca de serpiente

que trabaja antes del amanecer. Quiero dormir un rato,

un rato, un minuto, un siglo;

pero que todos sepan que no he muerto;

que haya un establo de oro en mis labios;

que soy un pequeño amigo del viento Oeste;

que soy la sombra inmensa de mis lágrimas. Cúbreme por la aurora con un velo,

porque me arrojará puñados de hormigas,

y moja con agua dura mis zapatos

para que resbale la pinza de su alacrán. Porque quiero dormir el sueño de las manzanas

para aprender un llanto que me limpie de tierra;

porque quiero vivir con aquel niño oscuro

que quería cortarse el corazón en alta mar.

Lorca also wrote poems which he called ‘gacela’, a Spanish adaptation of the ghazal. The gacela carries on the ghazal’s sense of a string of independent images, though it largely dispenses with the rhyme scheme and the organisation into couplets.

In this gacela, Lorca uses the form for dark, surrealistic imagery: hearts cut out, a decaying mouth, the ‘scorpian claws of the dawn’. There is a sense of being in a dangerous country: these were poems written towards the end of his Lorca’s short life, when Spain was getting darker politically, with the arrival of fascism in the early days of the Spanish civil war. Lorca was later murdered by Spanish nationalists, casting over the poem an even darker poem.

Gacela of Unforeseen Love

Federico García Lorca No one understood the perfume

of the dark magnolia of your belly.

No one knew you martyred

a hummingbird of love between those teeth. A thousand Persian carousels slept

in the moon plaza of your forehead,

while four nights I lashed myself

to your waist, enemy of snow. Among the plaster and jasmine, you saw

I was a pallid branch of seeds.

I sought through my breast

to give you letters of ivory saying always, always, always: garden of my last breath,

your body escaped forever,

the blood of your veins in my mouth,

your mouth already without light for my death.

(translated by Gilbert Wesley Purdy)

Gacela del Amor Imprevisto

Federico García Lorca Nadie comprendía el purfume

de la oscura magnolia de tu vientre.

Nadie sabía que martirizabas

un colibrí de amor entre los dientes. Mil caballitos persas se dormían

en la plaza con luna de tu frente,

mientras que yo enlazaba cuatro noches

tu cintura, enemiga de la nieve. Entre yeso y jazmines, tu mirada

era un pálido ramo de simientes.

Yo busqué, para darte, por mi pecho

las letras de marfil que dicen siempre, siempre, siempre: jardin de mi agonia,

tu cuerpo fugitivo para siempre,

la sangre de tus venas en mi boca,

tu boca ya sin luz para mi muerte.

This gacela is slightly nearer to the rhyming scheme of the ghazal, although the poet has arranged it in quatrains; it also retains the ghazal’s sense of a running rhyme. We see here the form being used quite loosely in a modernist, surrealist way. Lorca tips his hat to the mixed heritage of Andalusia, where he was from; the gacela is a way, for him, of bringing in something of the Islamic world into his contemporary Spanish poetry, similarly to the way, in his early poems, he drew on Gypsy traditions.

Tasks

One

Students can write poems – in either a strict ghazal form or a looser one – experimenting with a repeated mono-rhyme, possibly on the penultimate syllable. These rhymes might be thought of in advance, perhaps even as a group, or else allowed to emerge naturally in the composition of the poem. The focus should be on considering the different possible effects that this combination of a ringing rhyme with a refrain can have.

Two

Students can write a series of linked but separate couplets, each of which have their own individual weight, each focussing on a particular image, but which are also linked together to give them a second, cumulative weight. The focus should be on playing around with that balance between each couplet having its own individual sense and each couplet being linked together.