Spring 2022 Syllabus: 19.1.22

Welcome to Ludic Literature! Below you will find overviews and reading lists for each week of the module. They are indicative only: based on how our writing and conversation has been going, I am likely to adapt them and each week I will e-mail you a detailed briefing which will tell you how to prepare for seminar the next week. The reading for individual weeks may look a lot but often consists of a number of short texts. I arrange reading in order of priority, and if you feel it is too much talk to me. Towards the bottom of the reading lists for each given week, you are likely to find reading suggestions which are not core but are recommended (eg you may want to read).

There is the assumption that everyone will come to seminar ready to make a contribution to our discussion. Please always bring pen, paper and the texts. I ask students not to have laptops or phones open unless necessary, as it blocks them off from the conversation. Each week I will be encouraging, but not requiring, you to do a little writing. Playing with the texts we are studying by re-writing them is an essential to the idea of the module and you will get most out of it if you sometimes (not necessarily always) take up this invitation.

Assessment will be by one 5000-word essay, or a piece (or pieces) of creative writing (parody, transformation, transposition, or act of writerly play) of up to 1500 words, with a commentary of such length as to make up to 5000 words.

Teaching by one 3-hour seminar per week. Please arrive five minutes before the seminar. There will be two seminar groups, one on Thursdays, 2 – 5, one on Fridays, 10 – 1. Ludic seminars have been known to run over, and so you should, if possible, not schedule anything for the hour after the seminar. I am trying to balance the groups so that we have a good range of students from the various courses in each group, so I may ask a few people to swap groups in January. If so, I will let you know.

Books you need to have your own copies of are listed below (many or most of these can be obtained cheaply second-hand, and/or are in the library). All other readings will be given out each week in advance or placed on Blackboard.

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway. (Collins Classics) ISBN: 978-0007934409 [This edition please].

- Jorge Luis Borges, Labyrinths. (Penguin)

- Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire. (Penguin)

Week by Week Reading

Week 1 – Parodies and Imitations: Re-Writing Woolf

Overview:

We will begin the module by discussing its themes: play; imitation, parody, and transformation; and style and form. I will refer us to Virginia Woolf’s ‘How Should One Read a Book?’, to Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Good Readers and Good Writers’, and, more briefly, to Susan Sontag’s ‘On Style’, and to Henry James’s ‘The Art of Fiction’. For the module’s ideas about imitation, parody, and transformation I will refer us to Colin Burrow, Imitating Authors and to Gerard Genette, Palimpsests.

The aim of this initial week is primarily for us to try our own hands at parody and to think together about the ways in which parody, imitation, translation, reinvention are all themselves ways of understanding prior works of literature, the aim of this course being not only to study ludic literature but also to develop ludic modes of criticism. In previous years the ‘source texts’ we have used for parody have been Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, James’s The Figure in the Carpet, Joyce’s ‘The Dead’, George Eliot’s Silas Marner, and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. This year our source text will be Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, whose style we will talk about in its own right, and then subject to various metamorphoses via the historical styles parodied in the ‘Oxen of the Sun’ chapter of Joyce’s Ulysses. This process should cast light on Woolf, on the historical styles parodied by James Joyce in ‘Oxen of the Sun’, and on your own writing.

The main object of our discussion this week (and much of the second week) will therefore be your own parodies. You all need to have done one, as set out on the Week 1 briefing you should have (if you don’t have this, please e-mail me).

Reading:

1) Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway

2) Extracts from Joyce’s parodies of historical styles in the ‘Oxen of the Sun’ chapter of Ulysses, as reprinted in Dwight Macdonald, ed., Parodies: An Anthology (Macdonald has helpfully given each parody a label – Joyce didn’t). (Again, this is on Blackboard – you only need to print off the Joyce parodies.)

3) McDonald’s introduction to his anthology. (Also on Blackboard; you don’t need to print this off)

4) Virginia Woolf, ‘How Should One Read a Book?’ (Blackboard)

5) Vladimir Nabokov, ‘Good Readers and Good Writers’ (Blackboard)

6) Examples of re-writings people did the last three years, to inspire you. In 2013 and 2014, we used the beginning of Alice in Wonderland as our base text, in 2015 Henry James’s The Figure in the Carpet, in 2016 – 18 Joyce’s ‘The Dead’, in 2019 George Eliot’s Silas Marner, and in 2020 – 1 Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. But the principle is the same. (You will find these on Blackboard. Again, you don’t need to print these off.)

Also look at the example of Vijay Khurana’s re-writing of ‘The Dead’ through various styles in:

https://creativecritical.net/a-little-death/

7) You might also like to have a look at Impostures, a recent amazing translation/adaptation by Michael Cooperson of the medieval Arabic classic trickster tale-sequence, the Maqamat, by al-Hariri, into fifty different English styles – among them that of Mrs Dalloway.

https://nyupress.org/9781479800841/impostures/

The whole book is available as an e-book through UEA library but I have put some of the most relevant extracts – including the introductions and the parody of Mrs Dalloway – on Blackboard. You will find it in the Week 1 folder on BB, and also in the ‘Virginia Woolf and after’ folder – this also contains the opening of Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, which is a re-writing of Mrs Dalloway, and which you might be interested in reading for fun.)

8) You might wish to have a look at George Saintsbury’s A History of English Prose Rhythm (on Blackboard). This was Joyce’s primary source for the historical prose styles he was parodying in ‘Oxen of the Sun’ – for most (though not all) of the Joycean parodies, you will find a sample of source texts here.

Week 2 – Parody: Imitating and analysing voices. The continuity of a style (the case of Henry James)

Overview:

This week we will continue studying people’s re-writings from the first week, but adding to our repertoire some formal techniques for analysing prose style, from Richard Lanham, Ian Watt, and Geoffrey Leech and Michael Short. These techniques will inform your work on the rest of the module. I will be asking you all to prepare a close stylistic analysis of the opening pages of Henry James’s 1908 short story, ‘The Jolly Corner’, which we will discuss in seminar. We will then look at three examples of parody / imitation / re-writing. First, the famous parody of Henry James’s style by his friend Max Beeerbohm – painstakingly analysed by Seymour Chatman in his book on The Later Style of Henry James. Second, the imitation of Henry James’s style by John Banville in Mrs Osmond. And, three, the transposition of ‘The Jolly Corner’ by Elizabeth Bowen in ‘The Demon Lover’. I will also point you to the project edited by Philip Horne, Tales from a Master’s Notebook, in which a series of contemporary writers took fragmentary ideas for stories from James’s notebook and wrote them up – among them Tessa Hadley and Amit Chaudhuri’s.

There will be opportunities to write your own short parodies of James, or for you to develop one of the James fragments into your own story.

Reading:

1) Henry James, The Jolly Corner

2) Ian Watt, ‘The First Paragraph of The Ambassadors’ (on Blackboard, Week 2 – no need to print it, just read it; you should also have read the first paragraph of The Ambassadors)

3) Extract from Leech and Short, Style in Fiction (on Blackboard, Week 2) (concentrate on Chapter 3; just have a look at what they say in Chapter 4 on stylistic variation.) (No need to print this, just read it.)

4) Extract from Richard Lanham, Analyzing Prose (on Blackboard, Week 2) (Please read this, you don’t need to print it off).

5) Max Beerbohm, ‘The Guerdon’, and Sebastian Faulks, ‘Henry James’ and ‘Virginia Woolf’ (from Pistache) (Blackboard – please print off and bring to seminar)

6) John Banville, Mrs Osmond, opening pages (Blackboard – please print off)

7) Elizabeth Bowen, ‘The Demon Lover’ (Blackboard)

8) Fragmentary ideas for stories from Henry James’s notebooks as selected in Horne’s Tales from a Master’s Notebook (Blackboard)

9) I also recommend Tessa Hadley’s and Amit Chaudhuri’s attempts at writing up James’s fragments – ‘Old Friends’ and ‘Wensleydale’.

Week 3: Games with Translation

Overview:

Imitation, parody, and transposition belong in a continuum of ancient literary practices which extends to and includes translation – though some might argue that all of these practices should be understood as kinds of translation. This week we will be focussing on translations, playful and otherwise, and not least because looking at the same piece of writing in multiple styles and forms will help us to refine our sense of the difference that style and form make.

In the first part of the seminar we will be looking at one chapter from Adam Thirlwell’s 2013 translation-game project Multiples – in this case A. J. Snijders’s ‘Geluk’, translated and re-translated by Lydia Davis, Jeffrey Eugenides, and others.

In the second part of the seminar we will study multiple translations through time of the famous poem by Sappho, ‘He seems to be equal to gods that man’ (Fragment 31), translated, imitated, or sampled by many authors, including Addison, Smollett, Symonds, William Carlos Williams, HD, Robert Lowell, Bob Dylan, and, most notably perhaps, Anne Carson, who has spent her whole career meditating on, translating, and developing the implications of this fragment. Carson’s case is especially intriguing because we can watch her turning this poem into ideas, essays, and various poetic forms, and seeking analogies for it in different eras and culture (via Marguerite de Porete and Simone Weil). I will also be pointing you to two examples of novelization of Sappho, by Jeanette Winterson and Erica Jong.

There will be opportunities to develop Sappho’s style by working up some of her fragments.

Reading:

1) ‘Geluk’, multiply translated in Multiples (Blackboard; please print off and bring to class).

2) Sappho, Fragment 31, multiply translated. (Extracts from Margaret Reynolds, The Sappho Companion, and beyond). (Blackboard; please print off and bring to class.)

3) Anne Carson, Eros, the Bittersweet, opening pages. (Blackboard; please print off and bring to class.)

4) Anne Carson, If not, Winter, extracts (Blackboard; please print off and bring to class.)

5) Anne Carson, Decreation, extracts (Blackboard; please print off and bring to class.)

6) I also recommend you look at Jeanette Winterson, ‘Sappho’, in Art and Lies (Blackboard)

7) You may also enjoy looking at the opening pages of Erica Jong, Sappho’s Leap (Blackboard).

8) Theoretical perspectives on this week’s work are offered by Walter Benjamin, ‘The Task of the Translator’ (Blackboard) and Adam Thirlwell, Miss Herbert (opening pages) (Blackboard)

Week 4 – Imitations and Transformation

Overview:

This week we will be thinking about imitation and re-writing across time, culture, and form. It is the question which was asked by Renaissance humanist theories of imitation: that is, how would Cicero or Virgil write if they wrote ‘here’ and ‘now’, in English, in London, in 1590? We will explore re-writings of three major modernist writers – James, Joyce, Woolf – while also being able to consider further the transformations of Sappho from last week. This week I will also be introducing you to some of the theoretical reading on this topic. We will be reading three Dubliners short stories alongside re-writings of them in Multiples 100, and also reading the seed story of Mrs Dalloway, ‘Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street’, which will allow us to compare that to Dubliners and to the final novel of Mrs Dalloway. We will also be looking at the opening of Michael Cunningham’s re-writing of Mrs Dalloway, The Hours, and the imitation of Mrs Dalloway in Cooperson’s Impostures. If time permits we will revisit Tessa Hadley’s version of James.

This week you will be encouraged to write into the contemporary moment one of our source texts (eg Joyce, James, Woolf)

Reading:

1) James Joyce, ‘Araby’, ‘Counterparts’, and ‘Clay’ from Dubliners (Blackboard; print out and bring to class)

2) Re-writings of ‘Araby’, ‘Counterparts’, and ‘Clay’ by John Boyne, Belinda McKeon, and Michèle Kelly in Dubliners 100 (Blackboard; print out and bring to class)

3) Virginia Woolf, ‘Mrs Dalloway in Bond Street’ (BB)

4) Michael Cunningham, The Hours, opening (BB)

5) Michael Cooperson, ‘Woolf at the Door’, from Impostures, opening

6) Colin Burrow, Imitating Authors, introduction (BB)

7) (If time permits) – Contemporary novelizations of Sappho by Winterson and Jong

8) (If time permits) – We will return to imitation of James.

9) (additional examples of the re-writing of ‘Araby’): John Updike, ‘You’ll Never Know How Much, My Dear, I Love You’, and Flannery O’Connor, ‘A Temple of the Holy Ghost’

Week 5 – Reading week

This week is clear for reading and writing. I will be encouraging you to do plenty of reading in theory of style, form, imitation, parody, and play. [As noted above, if the baby comes earlier, this reading week will come earlier; and if the baby comes later, the reading week will come later.]

Week 6: The Play of Thought and Self: Kafka and Borges, the Essay and the Story

Overview:

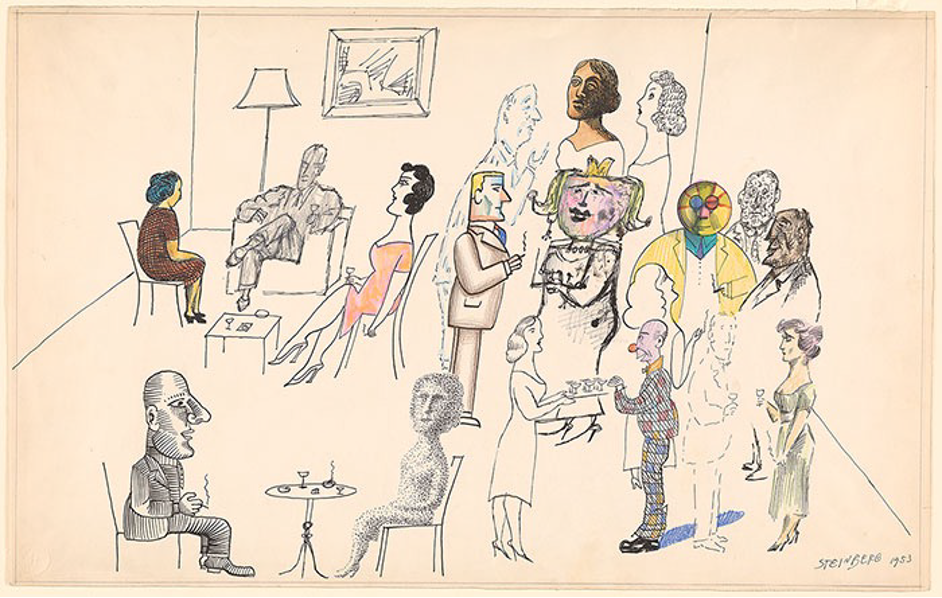

This week we will be exploring play with ideas and with the self, by following through the short stories and afterlife of Franz Kafka, the great maker of parables, paradoxes, and playthings. We will exploring how he was re-written by his great imitator, the Argentinian short story writer and essayist, Jorge Luis Borges. Borges developed out of Kafka’s (mock?) parables his own playful parabolic fictions, and as Ashbery says in his piece on Borges (up on Blackboard), each of the two writers “is obsessed by the same enigma: the fabulous complexity of the universe confronting man’s ridiculously inadequate attempts to unravel it.” Borges also drew from Kafka the inspiration for writing stories in the form of essays and essays in the form of stories. We will think about the relation of essays and stories (which will allow us also to look back at the earlier case of Anne Carson.)

We will then look at two later examples of Kafka and Borges’s influence: Lydia Davis shows a different path out of Kafka, while in Roberto Bolaño, we find another South American writer developing the example of Borges’s invented personae – and invented writers.

You will be encouraged to develop your own idea for an essay-story.

Reading:

1) Selected short stories and parables from Kafka, The Great Wall of China (Penguin). (On Blackboard). This contains ‘The Great Wall of China’ (pp. 58 – 70), ‘The Collected Aphorisms’, and selected Parables (pp. 79 – 138) (Blackboard)

2) Borges, Labyrinths – Fictions 1-6, Essays, and Parables.

3) Extracts from Lydia Davis, Collected Stories, including ‘Kafka Cooks Dinner’.

4) Robert Bolaño, extracts from Nazi Literature in the Americas, and ‘Sensini’, from Last Evenings on Earth.

Week 7: The Play of the Word: Gertrude Stein and Harryette Mullen

The minutest form of literary play is, perhaps, the play of the word, down to the play of the individual letter. Here we pass from the structured, law-like games in which Borges specialised, to their direct opposite, that play with uncertainty and indeterminacy which Jacques Derrida spoke of as the exact opposite of play, and whose instances in modern poetry Marjorie Perloff traces back to the influence of Arthur Rimbaud. We will reading some short extracts from one of the foundational works of modernism, Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons, a mysterious, seductive, infuriating text in which meaning is always fugitive and in play, and linguistic play and erotic play are scarcely distinguishable. A good way into Tender Buttons are the more accessible rewritings of its first two sections by contemporary American poet in Trimmings and S*perm**k*t. For Millen, Steinian puns, equivocations, jokes, riddles, and nonsense all awake the natural gaiety and play within language while exposing its unconscious ideology – around gender and race, in particular. We will also take the opportunity to read a few of the parodies of Stein that appeared around the time of Tender Buttons’s first publication.

This week we will be exploring the play of the individual word in the first section (‘Objects’) of Stein’s famous avant-garde masterpiece, Tender Buttons, and in the rewriting of it by the contemporary American poet Harryette Mullen in her Trimmings.

1) Gertrude Stein, Tender Buttons, Section 1 (‘Objects’) (Blackboard)

2) Harryette Mullen, Trimmings (reprinted in Recyclopedia) (Blackboard)

3) Marjorie Perloff, ‘Poetry as Word-System: The Art of Gertrude Stein’, in The Poetics of Indeterminacy, chapter on Stein (Blackboard)

4) Arthur Rimbaud, ‘Voyelles’, translated by Christian Bök. (Blackboard)

5) Parodies of Gertrude Stein, excerpted in Mock Modernism, ed. Diepeveen (Blackboard).

Week 8: Games with Form 1: Paul Muldoon and the sonnet

This week we turn to games with form by exploring how contemporary poets have played with the possibilities of the sonnet. We will begin by discussing different translations of one Petrarch sonnet before focussing on the Irish poet Paul Muldoon’s various games with the structure of the sonnet in two of his collections, Quoof and Meeting the British. We will also read some games with the sonnet-form by other contemporary poets, among them Geoffrey Hill, Terrance Hayes, Jericho Brown, Sophie Mayer, Bernadette Meyer, and Sophie Robinson, which use the sonnet form to raise questions about history, gender, race, and sexuality. In the case of Muldoon, we will also be continuing our discussion of play with metaphor and idea from the weeks on Borges and Muldoon.

You will be encouraged to think what a prose form of a sonnet would be – we will use as our inspiration Luke Kennard’s Notes on the Sonnets, a series of prose poems recasting Shakespeare’s sonnets.

1) Translations of Petrarch. (Blackboard.)

2) Paul Muldoon, Quoof and Meeting the British. (Blackboard.)

3) Assorted sonnets. (Blackboard.)

4) Chapter on the sonnet in Michael Hurley and Michael O’Neill, Poetic Forms. (Blackboard)

5) Luke Kennard, Notes on the Sonnets, extracts (Blackboard).

Optional Week (March 31 / April 1): Games with Form 2; Games with Constraint: Sestina and City

Overview:

This optional class will run, probably on TEAMS, in the first week of the Easter break (March 31 / April 1). You are encouraged to attend. Its focus will be on the writing under conditions of constraint that is most recently associated with the French OuLiPo group (whose most famous members are Georges Perec, Raymond Queneau, and Italo Calvino). But traditional poetic forms such as the sonnet, the sestina, the villanelle, and the pantoum, are themselves modes of writing through constraint. Writing through constraint is intended both to the liberate writing from inherited intentions, and also to expose the structures in which we live.

So as to develop our thinking from the previous week, we will explore the constraint of the sestina, which became a kind of postmodern obsession in the early 2000s, and set that OuLiPoean texts by Calvino and Perec, which play with actual structures: the city, the building, the room. We will also read a number of n + 1 poems by Mullen.

I will also recommend for this week a chapter of Caroline Levine’s Forms, which explores form both as a literary and as an ideological term.

You will be encouraged to try to turn a sestina into a city.

Reading:

1) Extracts from Oulipo: A Primer of Potential Literature (In ‘General Material on OuLiPo folder’; no need to print this out) (Blackboard)

2) Italo Calvino, ‘Cybernetics and Ghosts’; (in the ‘Calvino folder’; no need to print this out)

3) Assorted sestinas (Blackboard)

4) Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities (extracts) (Blackboard)

5) Georges Perec, Species of Space, extracts (Blackboard)

6) Raymond Queneau, 100 000 billion poems – http://www.bevrowe.info/Internet/Queneau/Queneau.html

7) Raymond Queneau, Exercises in Style (extracts) (Blackboard)

8) Caroline Levine, Forms, opening chapter. (Blackboard)

9) Gaston Bachelard, Poetics of Space, extracts (Blackboard)

EASTER BREAK

Over Easter, as well as preparing for the final two weeks of the module, you should be working on your final projects. I will be available to discuss these with you.

Week 9 – Games with Form III: Games with Plot: Coover, Calvino, Barthes

Overview:

This week we are turning our attention to games with plot. What happens when one plays with the structure and pace of a story? How can we analyse plot structure and movement? What is the relation between a plot and an argument? How does plot relate to other kinds of drive, including desire? How can we see plot as an element of style? And how do the plots of novels relate to those of myth?

The theoretical reading in narratology is quite difficult and narratological analysis is painstaking, so I will not set much additional primary reading this week. Rather, I will ask you to do the reading in narrative theory and then to test it against Mrs Dalloway itself, alongside a few examples of postmodern games with narrative structure – notably those of Coover and Calvino, as well as Joyce’s ‘Wandering Rocks’.

You will be asked to see what happens when you break up and re-structure Mrs Dalloway, possibly in the form of a sonnet, a sestina, or a city.

Reading:

1) Gerard Genette, Narrative Discourse, extracts (Blackboard)

2) Peter Brooks, Reading for the Plot, extracts (Blackboard)

3) Robert Coover, ‘The Gingerbread House’ and ‘The Magic Poker’ (BB)

4) Italo Calvino, ‘The Burning of the Abominable House’; ‘Prose and Anticombinatorics’ (BB)

5) James Joyce, ‘Wandering Rocks’ (Ulysses)

6) Frank Kermode, The Sense of an Ending, extracts (BB)

Week 10: Nabokov’s Pale Fire: Parody, Play, Game

Overview:

Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962) is an encyclopedia and summa of literary play, and the inspiration for this module. It will give us an opportunity to draw together all the themes and questions we have been discussing over the module: the play of styles, forms, words, languages, and plot structures. We will focus in detail on the text, which is more than sufficient, but I will point you to some relevant neighbouring Nabokovian texts.

You will be encouraged to try your hand at one or more of Nabokov’s games.

Reading:

1) Nabokov, Pale Fire

2) Nabokov, from Lecture on Russian Literature (Blackboard): chapter on Nikolai Gogol, especially the pages on ‘The Overcoat’ (pp. 19 – 28 and, especially, pp. 41-44) (no need to print this off)

3) Nabokov, ‘Breitensträter – Paolino’ (his essay on play)

4) Nikolai Gogol, ‘Diary of a Madman’ (Blackboard)

5) Nabokov, from Collected Poems, ‘An Evening of Russian Poetry’ (pp. 137 – 142) and ‘On Translating Eugene Onegin’ (pp. 153-4)

6) ‘Philistines and Philistinism’ (pp. 191 – 193); ‘The Art of Translation’ (pp. 195 – 198) (from Lectures on Russian Literature)

7) Nabokov, from Lectures on Literature (Blackboard): ‘Good Readers and Good Writers’ (pp. 1-8), discussion of parody in the ‘Nausicaa’ chapter of Ulysses (pp. 344 – 348), ‘The Art of Literature and Commonsense’ (pp. 371 – 381)

8) Simon Critchley, On Humour, chapter 1, pp. 1 – 25. (On Blackboard, folder labelled ‘Theory of Jokes’

A Little Death

By Vijay Khurana. A Little Death is a parody project in which the author rewrites the same passage of Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ again and again (and again and again), in various styles, in an attempt to reveal the secrets of one of the 20th century’s most influential short stories, while also exploring other writers and forms through the imitation of style.

Tim MacGabhann. Short Text on Parody

How has the practice of imitation (or parody etc.) affected your creative writing? I only ever seem to parody writers who intimidate me. During a Literature of the Americas course, I found myself reading Longfellow’s sonnets after the manner of Chaucer,...

Thomas Karshan. Teaching through Imitation, Parody, and Play

My purpose in the below is, at least initially, to offer, for all of those who are interested in teaching through imitation, a view of some of the main historical and theoretical issues and questions, as I see them, and to draw together in a single place some of the recent scholarship and thought on the topic. I will do so via an account of my own experience of teaching literature through imitation and parody in my MA module at UEA, Ludic Literature.