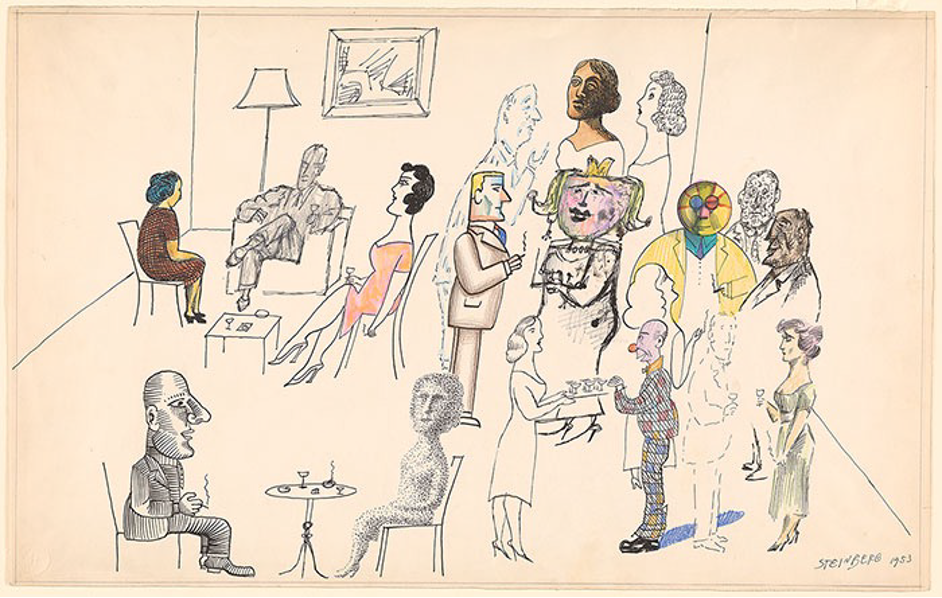

Saul Steinberg, ‘Techniques at a Party’ (1953)

Introduction

My purpose in the below is, at least initially, to offer, for all of those who are interested in teaching through imitation, a view of some of the main historical and theoretical issues and questions, as I see them, and to draw together in a single place some of the recent scholarship and thought on the topic. I will do so via an account of my own experience of teaching literature through imitation and parody in my MA module at UEA, Ludic Literature. I do so, however, in the awareness that I am only one of those of who have begun teaching somehow or other in this fashion. Among others are: Tom Roebuck and Will Rosseter, at UEA, Hannah Crawforth and Elizabeth Scott-Baumann at KCL, Nick Everett at Leicester, Catherine Maxwell at Queen Mary, Jeff Dolven at Princeton, Alicia Christoff at Amherst, Lindsay Reckson at Haverford, and Jeff Dolven at Princeton, and Roger Gilbert at Cornell; at extramural level, Tim Dooley at The Poetry School in London; and – championing imitative teaching at secondary school level in the United Kingdom, Barbara Bleiman from the English Media Centre.

So, for example in his 2nd year UEA module, ‘Reading and Writing in Elizabethan England’, Roebuck has his students draw on Sidney’s rhetorical and argument practices to write a defence of a modern genre; produce their own paradox in the mode of Erasmus, Rabelais, and Donne; or draw on the practice of Elizabethan minor epic to write their own imitative response to some aspect of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.[1] Rossiter, in his third year UEA module, ‘Unlike Them All, and Better? Englishing the Italian Renaissance’, asks his students to ‘compose an “original” sonnet in accordance with early modern principles of imitatio’, to translate in the manner of Chaucer, or William Stewart Rose, or of Harington; or to adapt ‘a section of a novella which Shakespeare either changes or omits in his play, in the manner of Shakespeare’.[2] Karshan, in his MA module ‘Ludic Literature’, asks his students to take a passage of a source text – in various years, Alice in Wonderland, The Figure in the Carpet, Silas Marner, ‘The Dead’, and Heart of Darkness – and re-write in one of the exaggerated parodies of historical English styles from the ‘Oxen of the Sun’ chapter of Joyce’s Ulysses (Bunyan, Pepys, Addison, De Quincey, Dickens, and so on), or to turn the same passage of a text into prose equivalents of Shakespearean and Petrarchan sonnets.[3] At King’s College London, Crawforth, in teaching her third-year module on Paradise Lost, has her students try to write like Milton, while in her module on the sonnet, Scott-Baumann asks her students to imitate Renaissancew sonnets. In her second-year module at Queen Mary on Nineteenth-Century Aesthetic Prose, Catherine Maxwell has her students to, for example, write an ‘impressionistic portrait’ in the mode of Pater’s famous account of the Mona Lisa in his The Renaissance.[4] Nick Everett at Leicester describes how in a module on poetic form he is able to get his students to write trochaics and iambics and, in doing so, better to understand some of the different effects each metrical unit is capable of, or in his module on American autobiography to attempt an autobiographical passage on the same themes of triumphing over adversity or educative progress from, respectively, Benjamin Franklin and Henry Adams.[5] Alicia Christoff describes her use of the ‘one-sentence pastiche’, ‘taking a famous line from a novel or short story and rewriting it in the style of an another author’ – here, from Austen or Proust, from Eliot into Dickens; Lindsay Reckson how she has her students write a one-page ‘creative imitation’ in the styles of, for example, Junot Diaz, Lydia Davis, Thomas Pynchon, or Gabriel García Márquez; and Jeff Dolven how in an upper-level course he has his student ‘write an essay about a short lyric poem on our reading list, using only the words of the lyric’.[6] Roger Gilbert has written on his success, in teaching Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons, in asking students to try to write their own pastiche imitations of Stein’s experimental text.[7] There is also a distinct history in Britain, of such means of teaching such as those practised by Tim Dooley in courses such as Sappho to Bashō and beyond.[8]

Overview of Module

Ludic Literature is a 12-week MA module (what in America is called a course), which I have taught at the University of East Anglia every year since 2013. The module is ‘creative-critical’ in that we explore together some of the major works of playful or ‘ludic’ modern literature across various languages, while also developing our appreciation of style and form by practising various forms of writing that are themselves ludic: imitation, parody, translation, and transposition between styles and forms. In play, we find, the boundary between the ‘creative’ and the ‘critical’ becomes unclear. The module is generally taken by a mix of students from the various critical and creative writing MAs (including the writing of poetry, prose, biography and non-fiction, and drama), as well as by students in in the MA in Literary Translation, and in Literature and Philosophy. One of my pleasures in teaching at UEA is this mix of ‘creative’ and ‘critical’ MA students in the classroom, and the conversations that that makes possible. Students of all kinds report finding that they grow as writers (creative and critical) by trying on, splicing, and revamping the various voices and styles they encounter.

When I arrived at UEA I had recently published a book, Vladimir Nabokov and the Art of Play,[9] and was keen to create an MA module which would explore play and the ludic across modern literature. The module ends with Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962), a kind of encyclopaedia in miniature of every kind of readerly and writerly play. On the ‘critical’ side, the module traces the evolution of leading postmodernist styles and themes, especially ludic ones, back to their origins in Dostoevsky, Joyce, Kafka, Borges, and Nabokov. Using these influential authors as a starting point, we read a range of ludic authors, passing back and forth between languages, nations, and genres. Each week we usually pair two authors. In previous years we have for example, read Dostoevsky against Nabokov, Kafka against Borges, Perec against Queneau and Calvino, Carter against Coover, Muldoon against Heaney, Pynchon against Barthelme, and Ashbery against Mallarmé.

But it quickly became apparent to me, once I had started teaching the module, that we would be missing all sorts of opportunities if work for class had been limited to a discussion of the materials: partly because at least half the students in the classes are creative writing students, and partly because so many of the writers we were studying themselves provided models of such playful responses to prior literature. Most – perhaps all – of the writers we study were sceptical of the professional and formalised literary criticism, set out in the form of discursive essays and theses, that we now usually teach students to do and write in literature departments; for Nabokov, as for Proust, Auden, Pound, Woolf, and many others, the right way of studying and responding to a work of literature was not to ‘talk about it’, or interpret it, or to position it historically, or to offer a scholarly analysis of its purposes, but to rewrite it, play with it, parody it, and reinvent it. And this was a formula not only for the study of literature but for the way they wrote it – a creative writing programme founded not principally on students writing out of their experience, but out of their reading. Some of those modernists – Pound especially – were well aware that they were recapitulating the literary and educational programme that was known to Renaissance humanists such as Petrarch and Erasmus as imitatio. For me and my students, it has been a source of growing excitement to realise that we were recapitulating many of the practices of Shakespeare’s schoolroom at Stratford Grammar School, of Milton’s classroom at St. Paul’s – on this, more below.[10] I will add at this point, however, that we do not limit ourselves to imitation (and its various cousins and near-analogies – parody, transposition, continuation, pastiche, burlesque, and so on). From early on in the module, we also practice analytic criticism of the kind that has been refined from 1940 onwards in university English departments; indeed we practice some pretty intense close stylistic analysis, informed in some cases by stylometrics and involving, on occasion, the x-rays of a style offered by numerical computation – of the varying percentages of nouns, verbs, and adjectives in several pieces of prose, for example.

I always begin the module with two weeks focussing on the students’ own writing. In advance of the module, over the winter holiday, I ask each of them to try their hand at re-writing a source text into another style – I call this exercise ‘transposition’, drawing on a metaphor from music education. For convenience I have for many years used for the ‘target styles’ the exaggerated and rather caricatured parodies of historical styles of English prose (such as Bunyan, Gibbon, De Quincey, and Gibbon) written by James Joyce for the ‘Oxen of the Sun’ chapter of Ulysses – https://www.joyceproject.com/index.php?chapter=oxen¬es=0#.Ykrz1pNBxQI –The source text changes every year or two: in the first couple of years, I started with Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; since then, we’ve had Henry James’s ‘The Figure in the Carpet’, George Eliot’s Silas Marner, and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. (I choose source texts for their stylistic richness, and, sometimes, relevance to our themes of style and parody.) I then print off all the students’ work, so that each student gets a copy, and we spend the first two weeks discussing their writing.

The first time I asked students to do this, I came to class nervous as to whether any of them would have done it – or done it well. I need not have worried. It turns out that people are natural mimics – not for nothing does Aristotle say: ‘Imitation is natural to man from childhood, one of his advantages over the lower animals being this, that he is the most imitative creature in the world, and learns at first by imitation.’[11] And it was not just the ‘creative writers’ who turned out to be good at it. (In fact, I have also had success with this method with first year undergraduates at UEA.) It makes for a fun beginning to our week’s work for the semester, encouraging students to get to know each other, and placing the emphasis where I want it to fall for the rest of the semester: on the students’ own voices, their own writing and thinking. Examples of work students have done in this vein can be found here: Student examples

Over the course of the semester, the kinds of rewriting we do gets ever more complex. I have at various times encouraged my students to attempt to write like each and any of the authors we have studied, whether that be Franz Kafka or Jorge Luis Borges, Salman Rushdie or Angela Carter, Seamus Heaney or Paul Muldoon, Gertrude Stein or Harryette Mullen. We have read Kafka’s short tales against Borges’s re-writings of them, tried to write like Kafka or Borges, turned a Kafka story into a Dostoevsky paragraph or a Nabokov poem. I often encourage students to use as their base text for these imitations the source text with which they began in the opening weeks (such as Carroll, or Conrad), one advantage of which is that everyone in the class already knows the text that is being transposed. Students approach this task in various ways – for some it is an opportunity to develop their own material in the style of Kafka or Muldoon, for others to see what happens if they use their own voice and style to develop the stories, ideas, characters, or themes of, say, Rushdie or Borges – click here for an example. Inevitably all this raises the fundamental question of the relationship between content and style – on which I will say more below.

In the second half of the seminar, as our attention turns from style to form, we experiment with turning material from one form to another. Often we begin with sonnets, and look at how Surrey and Wyatt translated the same Petrarch sonnet into two different sonnet forms (which we now know as the Petrarchan and Shakespearean sonnets), and explore various ways in which contemporary poets, among them Geoffrey Hill, Paul Muldoon, Sophie Mayer, and Terrance Hayes, have played with, mutilated, or broken the form of the sonnet. I encourage students to write the same sonnet twice, once in Petrarchan and once in Shakespearean form, and to see how that changes the material. I ask students to turn a sonnet into a sestina, a villanelle, or a pantoum, and in doing so to see what difference all of that makes to the poem – click here for some examples – Students have also experimented widely with turning verse forms into prose: what, we have asked, would it look like to write a prose equivalent of a Petrarchan, or a Shakespearean sonnet? What would it be if the same short story were written ‘in the form’ of a villanelle or a pantoum? Conversely, we have experimented with turning prose into various forms of verse, taking, for instance, a story by Coover and re-written it as a sestina, two kinds of sonnet, and a villanelle. In doing all this, we are asking fundamental questions not only about play but also about style and form, how they shape meaning and make possible certain kinds of writing and thinking.

Some Historical Background, Renaissance and Modern

It was only some years into teaching the module that I became aware that every one of the pedagogical exercises we were practising had its precedent in the Renaissance school-room. When Shakespeare was at Stratford Grammar School in the 1560s, he would not have spent his time writing essays about Ovid or Cicero, as GCSE or A-Level students today write essays about Shakespeare, Austen, or Orwell; nor would have even discussed their themes, images, or ideas. There was some historical commentary and thematic explication akin to that of modern literary study. ‘Declaring the argument and scope of the author means providing some framing information (historic, generic, philological) and perhaps offering a sententia or prudential maxim under which the sense of the whole might be gathered.’[12] But this was only an intermediary stage before the student, growing older, would move on to the main business: memorisation, grammatical drills, translation, imitation, and composition, all with the final end of making the child proficient writer of correct and elegant Latin. The young Shakespeare will have memorised Cicero or Ovid, so as to get by heart their stock phrases, ideas, grammatical turns, and rhythms. He will have expounded the grammatical principles exemplified in his writing. He will have practised re-casting the same sentence, or sententia, into many different forms according to strict rules; or writing a sentence in the same form, but changing the theme, from – for example – ambition to avarice. He will have undertaken ‘double translation’ – turning a passage of Cicero into English, setting it to one side, and then turning it back into Cicero’s Latin, or into the Latin of Terence or Caesar. Eventually he will have been given a sample of English and asked to write it in Ciceronian Latin. The master, looking at the work, could then point out where the student had erred, saying that Cicero would have used this word, not that, employed this grammatical construction, not that, shifted from this rhetorical figure or theme, image, or idea, to that – and not such as the student had written it. The young Shakespeare will have been asked to re-write prose as verse, verse as prose. He might, as the boys at St. Paul’s were, have been asked one day to turn a passage of the Psalms into Latin verse, another day to turn the same passage into Ciceronian prose. He would then have reached then point of writing his own prose and verse compositions, beginning with epistles, then themes, then orations. He would also, as he grew older, have taught the younger boys, as he when young had once been taught by them.[13]

We can guess all this not because we know very much directly about Stratford Grammar School in the 1560s – we don’t – but because we have evidence of what happened at other 16th century British schools (Westminster, Eton, St. Paul’s, and others) and several pedagogical manuals; and because all these schools, and manuals, were following and enunciating the pedagogical principles that had been laid down by the humanists of the late 15th and early 16th century, notably Erasmus, whose 1511 pamphlet De ratione studii, or, On the right method of instruction, was widely read in 16th century England and ‘forms the fundamental philosophy of the grammar school in England.’[14] What Erasmus sets out is the pedagogical part of the broader cultural programme he promoted alongside other humanists such as Petrarch and Poliziano, and which they summed up in the word imitatio, a term that covered the pedagogical exercises mentioned above but which also formed the core of Renaissance literature, encompassing the imitation, translation, and transposition of great works of the past into the present, with the ultimate object of making those works live again in the new worlds in which they were being reborn. It was a was ‘a literary technique that was also a pedagogic method’.[15] There is a seamless continuity between the school education Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and Milton enjoyed, and the writing they would go on to do.

This in fact formed the programme for literary education in the Western world for many centuries to follow, so long as that education was principally an education in Latin and Greek – and in fact there are still distant embers of it in the contemporary world, in the Classics instruction at Oxford and Cambridge university, where composition in Latin and Greek prose and poetry are still options (though no longer mandatory). It was a pedagogical programme which stressed style over content: which, indeed, viewed style as governing content, and as the fount of future thoughts. It entailed a continuity between learning and teaching, childhood and adulthood, and, above all, reading and writing, seen as two sides of the same coin. It took it for granted that to read well great authors of the past entailed learning to write like them. It was, in that sense, more like what we would now call an education in ‘creative writing’, but one founded on an attention to previous great works, especially to the imitation, translation and transformation of their styles, and as such it had what we might now call a ‘critical’ quality.

All this is notably different from what we now take for granted as a literary education, whether on the ‘critical’ or on the ‘creative’ sides, and above all because these are now decisively separated from one another. This is above all a consequence of the way that the teaching of English and other modern languages evolved, when they began to supplant Latin and Greek as the main focus of literary education, beginning in the late nineteenth century.

Literary criticism as now practiced in schools and universities consists of a far wider range of intellectual procedures than Shakespeare would have encountered. There persists some teaching of the ‘close-reading’ first developed in the period from 1930 to 1970. This will certainly involve a close analysis of individual linguistic features, but is far less likely to encourage students to place these features as characteristics of a continuous style, whether by style we understand a manner individual to the author, or one category in the formal system of styles recognised by Renaissance teachers. But pride of place goes to the paraphrase and interpretation of themes and ideas, whether explicit or implicit, and to placing the work of literature in its historical contexts, whether they be literary, religious, philosophical, social, or political. Perhaps the most decisive difference, though, is in the methods of teaching and assessment. Students now typically learn by discussing things in a seminar, and then write their thoughts up in essays which make an argument, supported by textual evidence. What they do not do much of, especially not at higher levels, is what Shakespeare would mostly have done: that is, imitated, translated, transposed, and parodied the authors he was studying. (Though these procedures are in fact used in some parts of the school system in the UK, especially with younger pupils.)

These techniques are also not much used in creative writing teaching, especially not that of prose. (The same is not quite true of creative writing teaching of poetry.) Here the emphasis is rarely on learning to write by imitating earlier writers. The three watchwords of the modern creative writing programme have been summed up as, ‘Write what you Know’, ‘Find your Voice’, and ‘Show don’t Tell.’[16] Each of these three principles runs directly against the assumptions of Renaissance imitative pedagogy, which assumes that you find your voice by imitating previous voices, that a great deal is shown by the style in which you tell something, and that you can come to know a great deal by trying on the voices and thoughts of others, and not merely out of ‘experience’.

Both halves of modern literary education are much more recent than most people realise. The literary students of ‘English’ in the late 19th century or early 20th century did very little interpretation and analysis, still less ‘close-reading’ or ‘creative writing’. They summarised, provided historical explanation, described characters, memorised, and engaged in the philological study of older forms of the language. They might also engage in some light belle-lettristic appreciation. Translation was undertaken, but not with any aim of imitation or composition.[17]

What displaced all this were the developments of the 1930s and 1940s. In America, the New Critics such as Cleanth Brooks and W. K. Wimsatt, and in the UK, William Empson and F. R. Leavis, established modes of close-reading and analysis which have over time been codified into the methods practised by countless school and university students of literature across the globe. Even so, the largely value-neutral, objective, and analytic-historical essays that students of literature are now asked to write are a long way from the criticism that Brooks, Wimsatt, Empson, and Leavis wrote and fostered, in which taste, judgement, and evaluation were always both guide and aim. In fact this criticism, though divorced from composition, aimed to put the student in the position of the writer. For the New Critics, as D. G. Myers summarises it, ‘to write a poem […] was to decide critically among the many creative directions it might take; to read it was to re-enact these decisions. And to write criticism, then, was to duplicate the poet’s experience – in a different medium.’ The New Critic R. P. Blackmur wrote that ‘“the composition of great poem is a labor of unrelenting criticism, and the full reading of it only less so; … the critical act is what is called a “creative” act, and whether by poet, critic, or serious reader, since there is an alteration, a stretching, of the sensibility as the act is done.’[18]

Conversely, the teaching of creative writing in its origins was understood to be a contribution to the critical understanding of literature. It did not aim, principally, at producing new novelists, poets, or playwrights. The first modern programme of creative writing was established at the University of Iowa in the 1940s by Norman Foerster, who wrote in ‘The Study of Letters’ (1941), that ‘one of the best ways of understanding imaginative literature is to write it, since the act of writing – the selection of materials, the shaping of them, the recasting and revising – enables the student to repeat what the makers of literature have done, to see the processes and the problems of authorship from the inside.’ Foerster was one of the ‘New Humanists’, a grouping that in the 40s was allied to the New Critics, and which consciously looked back to the model of the Renaissance humanists. Foerster hails ‘Petrarch, Poliziano, or Erasmus’; not aimless researchers but scholars, willing to perform preliminary labors but intent upon humane ends, critical and creative’.[19] And when creative writing started in Britain at the University of East Anglia in the early 1970s, the aim of Malcolm Bradbury, and others, was likewise to give students an understanding of literature deriving from an experiencing of attempting its making.

An example from Virginia Woolf

In the first seminar of Ludic Literature, I always have the class read aloud several paragraphs from an essay by Virginia Woolf, ‘How Should One Read a Book?’, which Woolf originally gave as a talk at a girls’ school in 1926. I will give some extracts from it here, because I think it raises many of the fundamental issues which I want to explore in the rest of this essay.

Woolf begins by saying this:

To read a book well, one should read it as if one were writing it. Begin not by sitting on the bench amid the judges but by standing in the dock with the criminal. Be his fellow worker, become his accomplice. Even, if you wish merely to read books, begin by writing them. For this is certainly true – one cannot write the most ordinary little story, attempt to describe the simplest event – meeting a beggar, shall we say, in the street – without coming up against difficulties that the greatest of novelists have had to face.[20]

(In the draft of her talk, she had told the girls that they should ‘think of a book as a very dangerous and exciting game, which it takes two to play at’.[21])

Woolf goes on to propose a thought-experiment: ‘let us imagine how differently Defoe, Jane Austen, and Thomas Hardy would describe the same incident – this meeting a beggar in the street.’ She begins by imagining how Defoe would describe the scene:

Defoe is a master of narrative. His prime effort will be to reduce the beggar’s story to perfect order and simplicity. This happened first, that next, the other thing third. He will put in nothing, however attractive, that will tire the reader unnecessarily, or divert his attention from what he wishes him to know. […] Further, he will choose a type of sentence which is flowing but not too full, exact but not epigrammatic. His aim will be to present the thing itself without distortion from his own angle of vision. He will meet the subject face to face, four-square, without turning aside for a moment to point out that this was tragic, or that was beautiful; and his aim is perfectly achieved. (65)

Woolf then goes on by sharply contrasting this with how Jane Austen would manage the same material:

But let us not for a moment confuse it with Jane Austen’s aim. Had she met a beggar woman, no doubt she would have been interested in the beggar’s story. But she would have seen at once that for her purposes the whole incident must be transformed. Streets and the open air and adventures mean nothing to her, artistically. It is character that interests her. She would at once make the beggar into a comfortable elderly man of the upper-middle classes, seated by his fireside at his ease. Then, instead of plunging into the story vigorously and voraciously, she will write a few paragraphs of accurate and artfully seasoned introduction, summing up the circumstances and sketching the character of the gentleman she wishes us to know. ‘Matrimony as the origin of change was always disagreeable’ to Mr Woodhouse, she says. Almost immediately, she thinks it well to let us see that her words are corroborated by Mr Woodhouse himself. We hear him talking. ‘Poor Miss Taylor! – I wish she were here again. What a pity it is that Mr Weston ever thought of her.’ And when Mr Woodhouse has talked enough to reveal himself from the inside, she then thinks it time to let us see him through his daughter’s eyes. ‘You got Hannah that good place. Nobody thought of Hannah till you mentioned her.’ Thus she shows us Emma flattering him and humouring him. Finally then, we have Mr Woodhouse’s character seen from three different points of view at once; as he sees himself; as his daughter sees him; and as he is seen by the marvellous eye of that invisible lady Jane Austen herself. All three meet in one, and thus we can pass around her characters free, apparently, from any guidance but her own. (65-6)

She goes on to reimagine the same scene as Thomas Hardy would have written it, but that is sufficient to demonstrate what Woolf is doing. There are several points to be drawn out.

First, we see what a wonderful brisk critic Woolf is, and how much can be said so quickly. One can learn more about Austen from these paragraphs than from many scholarly books on her work: what kind of people Austen is interested in, what she sees and does not see, and how she will situate a character she has chosen (here, seated at the fireplace, at his ease). How she will work up to a subject, accurately, but with artful ‘seasoning’. How she arranges a ‘corroboration’ between narrator and character (this relation between characters and narrators is different for every author). How she allows characters to ‘reveal’ themselves by their talk. How she builds up a character by multiple perspectives, so different from Defoe’s ‘four-square perspective’, expressed in his sentences which are ‘flowing but not too full, exact but not epigrammatic’; so different, implicitly, from Austen’s. And how the reader of Austen is granted almost complete liberty to move admiringly around her characters, with only her guidance – which, implicitly, we hardly resent; and this, again, is implicitly different from the sense of space we have when we read Defoe.

Second, that Woolf has what one might call a total view of style, in which everything hangs together in a writer. To write sentences as Jane Austen does is to see the world as she does – or rather, to see some things and not to see other things (beggars, for example). It is to have a particular sense of how we learn about other people, how life unfolds in plots, how people do or don’t reveal each other, and so on. Woolf shares this absolute view of style with the other great modernist writers: indeed, it may be the most distinct and significant thing about the artistic movement we know as modernism. We find it perfectly expressed, for example, in Marcel Proust’s 1920 critical essay on Gustave Flaubert, so close in spirit to Woolf’s essay. Proust writes that Flaubert is a writer who, by the entirely novel and personal use that he made of the past definite, the past indefinite, the present participle and certain pronouns and prepositions, renewed our vision of things almost as much as Kant, with his Categories, renewed our theories of Cognition and of the Reality of the external world.[22]

That is to say, Flaubert has, by his utterly novel way of using certain the various tenses, certain pronouns and prepositions, revolutionised our way of looking at the world as surely as did Immanuel Kant, the greatest philosopher of the modern age, when he overturned the world-view of Empiricism.

This view of style is not merely total. It is, we might say, sovereign – what Flaubert himself called ‘an absolute manner of seeing things’.[23] Style comes first, and dictates all the rest of a vision. As Proust writes elsewhere, style is: ‘intellect transformed, which has been incorporated into matter […] And is this transformation of energy, where the thinker has vanished and has drawn the things themselves before us, not the writer’s first attempt at style?’[24] For this reason you will get the whole of a writer if you can catch, repeat, and continue their voice. And for this reason, Proust matched his analysis of Flaubert’s style with an imitation of Flaubert – one in fact of a series of such ‘pastiches’ of recent French writers which he had originally intended to publish accompanied by critical analyses of each writer’s style. Proust said that by reading an author one soon makes out ‘the tune under the words,’ and that “when one catches the tune, the words (other words, naturally) quickly emerge.’ Once you learn a voice, you will be able to go on with it, and say the kinds of things the author would say, and think and see the world their way – but, in both cases, in new and unexpected circumstances. Once you catch a rhythm – the tune beneath the words – you can go on with it indefinitely. Proust says of his pastiche of another writer, Renan: ‘I have set my internal metronome to his rhythm, and I could have written ten volumes in this vein.’[25] To catch a writer’s voice is to make the same connections between things, impressions and ideas that they make – which, for Proust, is the essence of style. Proust wrote: ‘I think that the boy in me who has fun (doing pastiches) must be the same one who as a finely tuned ear for hearing, between two impressions, two ideas, a very subtle harmony that not everyone can hear.’[26] Parody and analysis meet, for Proust. Thus: […] when, in the old days, I wrote a pastiche – execrable as it happens – of Flaubert, I had not asked myself whether the melody I could hear inside me depended on the repetition of imperfects or present participles. Otherwise I should never have been able to transcribe it. It is an opposite labour I have accomplished today in seeking hastily to note down these few peculiarities of Flaubert’s style. Our minds are never satisfied unless they can provide a clear recreation of what they had first produced unconsciously, or a living recreation of what they had first patiently analysed.[27]

Returning to Woolf, we can add a third point to the two already made about ‘How Should One Read a Book?’ And that is, that to re-write a given scene in the style of another writer is entirely to transform all the details the subject matter, and not just the ‘treatment’ of that material. As the modernist poet Wallace Stevens neatly put it, ‘a change of style is a change of subject’.[28] A crude example can stand as symbol of the subtler truth. A beggar in Defoe is not a beggar in Austen, because there are no beggars in her vision, in her sentences: that beggar must be translated into ‘a comfortable elderly man of the upper-middle classes’, just as the ‘open air’ must be translated into close quarters, and ‘adventure’ into the estimation of character.

Woolf is quietly working her way up to a way of thinking about authors which is markedly different to the one we are accustomed to in modernity. ‘Austen’ or ‘Defoe’ appears here not as the author of a set number of texts, to be read, studied and interpreted, but rather as the name for a principle of writing, a style, a way of looking at the world, which can be applied to pieces of life Austen and Defoe never wrote about. Still more subtly, we are effectively being asked to imagine how Austen or Defoe looked at the world around them and transformed it into their novels; and it is that transformation, not the texts themselves, which we are asked to see as essential to them – a principle that can be transported, so that you might come away from reading Emma having learned to see the world around you through Jane Austen goggles, and to write about it with a Jane Austen pen. The more different one’s world is from Jane Austen, the harder the task is, – and the more probing, about Jane Austen, and about oneself. How would Austen have written about twitter? Or about aeroplanes? Or about trans-sexuality? And what styles would Austen have written in now, if she were writing now? These questions force one to ask about the place in Austen of the aphorism, the letter, communication; transport, and speed; sexuality, and gender – and what is distinctive to how Austen treated those issues and modes, and did so differently from her contemporaries. Jane Austen was not old-fashioned for her time, and if someone were to try to write about our world now in a way that expressed contempt for twitter, because Austen did not write of it, or to express the same views on gender as Austen, they would not be writing like Austen; because that would be to write in ways that are deliberately anachronistic, and Jane Austen was not deliberately anachronistic. Austen makes allusions to various contemporary poets, such as Thomas Gray, but if a writer in 2021 were to allude to Gray now, they would not be writing like Austen (a better equivalent might be McEwan). Austen’s prose style is considerably indebted to Samuel Johnson’s, but if someone in 2021 were to write prose so close to Johnson’s, they would not quite be writing like Austen. To do otherwise would be not to imitate Austen but to produce a pastiche of her work.

In brief, the contemporary writer who is absorbing an earlier writer is looking for equivalents in their own world, culture and language: for what and how Austen wrote; and for what she was writing against or with, transforming, criticising, or celebrating. As one critic said, commenting on James Baldwin’s close relationship with Henry James: ‘imitators of James today … made the mistake of choosing similar subjects to those of James’s novels. If James were alive today and living in the U. S., he surely wouldn’t write about the class division and relationships. What would fascinate him would be the line where whites and blacks met; to a contemporary James, race would be what class had been to the real James.’[29] That is to say, any imitator of a previous writer must seek to reproduce the difference the previous writer had with their world.

There is a clear parallel here with the task of the translator, who must always be on guard to avoid the pitfall of translating the distinctive original style of their text into a merely conventional style in the target language (one must not aim to produce a translation which ‘reads smoothly’, unless the original does). Rather, their task is to seek a style in the target language which is as original (or not) as that of the style of the writer they are translating – or, still more complexly, which deviates from the languages and styles of the day in something like the same way that the original deviated from the languages and styles of its day. Vladimir Nabokov summed this up in the following complex image for translation (this from his novel, Bend Sinister):

It was as if someone, having seen a certain oak tree (further called Individual T) growing in a certain land and casting its own unique shadow on the green and brown ground, had proceeded to erect in his garden a prodigiously intricate piece of machinery which in itself was as unlike that or any other tree as the translator’s inspiration and language were unlike those of the original author, but which, by means of ingenious combinations of parts, light effects, breeze-engineering engines, would, when completed, cast a shadow exactly similar to that of Individual T – the same outline, changing in the same manner, with the same double and single spots of suns rippling in the same position, at the same hour of the day.[30]

Some Renaissance Problems around Imitation

I have recapitulated here some puzzles which were central to the debates around imitation in the Renaissance, and which have recently been set out in Colin Burrow’s book Imitating Authors (2019), a book which I draw on extensively in this section. Renaissance humanists were clear that to imitate a great author well was to do something quite other than slavishly to rehearse their words, phrases, and ideas. The most famous and important locus of this idea is the debate around the imitation if Cicero, generally taken as the model of good Latin prose. In his 1528 book Ciceronianus, the Renaissance humanist Erasmus caricatured those ‘Ciceronians’ who, he said, refused to use any word or grammatical form which Cicero had not used. But Cicero, as Erasmus and his allies pointed out, was such a good stylist because he always spoke and wrote appropriately to the occasion, his audience, and his age. To write now, in another age, and to another audience, exactly as Cicero had, would not in fact be to write like Cicero, for Cicero was not an antiquated writer in his day – just as to try to write exactly like Jane Austen now, in 2021, would not in fact to write like Jane Austen. Erasmus says in a letter, if Cicero were alive today, he would laugh at the literalistic ‘Ciceronians’.[31] Renaissance writers on imitation had a series of ways of describing such bad, misguided practice of imitation: this was not true imitation, but mere aping, parroting, or shadowing, and produced merely ghosts, simulacra and shadows (Burrow 113; 116). Rather, the true imitation resembled the original obliquely in the way a son might resemble a father (149). The imitator, Renaissance commentators said, should fully digest the original, and so draw its strength and energy into their own; they should cultivate the original as a farmer cultivates the soil, so as to grow new crops from it; they should even see themselves as reincarnations of earlier writers, allowing the soul of the great predecessor to enter their bodies. They might even seek to out-run or wrestle with their original, to beat and master them. (6; 94 – 6)

In all of this, Renaissance authors were drawing on a body of theory about imitation bequeathed by ancient commentators, especially the ancient rhetorician Quintilian, who in his Institutes of Oratory had insisted that to become a good writer one must go beyond absorbing the rules of style from one’s exemplars. One must develop from their model ‘that assured facility which the Greeks call hexis’. That is to say, to imitate a previous writer, to enter into their model and to reincarnate them, is to learn the skill of writing as they did, and not merely their surface mannerisms (5; 68-70) It is, emphatically, not merely to merely to use the same words as Cicero, or even to å their sentences the same way as he did: Quintilian mocks those ‘who thought that they had produced a brilliant imitation of the style [genus] of that divine orator, by ending their periods with the phrase esse videatur.’ (175) Philipp Melanchthon, writing shortly after Erasmus’s Ciceronianus, said that true imitation consisted not in using the same words as the exemplar, but in imitating what he called their collocatio – which ‘can mean the ordering of juxtaposition of words, but […] can extend upwards to encompass the ways an author structures sentences or his habitual methods of connecting arguments together.’ (212-3) To imitate separately one part or another of the author, whether their word-choice, or their sentence-structure, or the way they form ideas, is not enough: the essence of a writer is in their whole, not in any of their parts (204). What the imitator is looking for in the original, some commentators said, is what they at different times called the ‘idea’ or ‘form’ or ‘spirit’ of the original, the principles underlying the way that author – whether it was Cicero or Virgil – or, take Woolf’s example, Austen or Hardy – wrote.

The question remained how to translate that principle from one age and culture to another. After all, Cicero was responding to, criticising, and celebrating authors and ideas of his own age, and transforming authors who preceded him. So, the contemporary imitator must look for equivalents to those authors in their own time. As Samuel Johnson said: ‘the ancients are familiarised by adapting their sentiments to modern topicks, by making Horace say of Shakespeare what he originally said of Ennius.’ (9) And, still more, the imitator will need to how the previous author responded to and transformed his sources. Roger Ascham said that ‘one who intelligently observes how Cicero follow others will most successfully see how Cicero himself is to be followed’ (14), and Johannes Sturm insisted ‘that the imitator of Cicero needs to know how Cicero read Demosthenes and how Cicero transformed what he read’ (223). What makes an author who that author is, then, on the one hand their hexis – a skill which the imitator tries to learn from them – but also what one might call a principle of difference between them and their contemporaries. Cicero himself had said that ‘If Thucidydes himself had been alive at a later date he would have been more mellow and less harsh.’ (176) So it is not enough to catch the writer’s voice or way of putting ideas together. Still more subtly, as Burrow puts it, an author is to be understood ‘not as a specific body of texts or a particular set of words, but as a set of principles of composition which can be adapted to new circumstances’ (9), ‘a transhistorical principle that can be described in the subjunctive’, so that ‘each particular text is produced from the interaction between those skills and dispositions and a particular occasion, be that a set of historical events, or an audience with distinctive needs and interests.’ (176) You might even, Burrow suggests, think of the author as a kind of ‘algorithm that could generate more works of a similar kind’ (24).

There are two significant caveats.

First, it is dangerous to assume that there is something fixed and single in the ‘occasion’ or ‘culture’ or ‘language’ onto which this algorithm of an authorial style might be applied. The example of Cicero is in this case somewhat deceptive because, as an orator speaking in political and legal contexts, he really did have in mind specific knowable audiences and particular occasions, for which conventions of discourse already existed, to which a style needed to be adapted. But the case is different for a writer such as Virgil or Ovid, Milton or Ben Jonson, Austen or Hardy. The privilege of a writer – as opposed to an orator – is to assemble their own context out of other texts, some of them contemporary and some of them historical (indeed this is exactly what is happening when Milton, imitating Virgil, makes him his contemporary). Partly by virtue of doing that, and partly by force of their style, they will re-invent their occasion and their audience. To assume that an imitator working today must translate Ovid or Austen into one of the styles of 2022 is to treat one’s own culture as a given, in a way that Ovid and Austen did not themselves necessarily do. Burrow quotes John Dryden, saying in the introduction to his translation of the Aeneid that he had ‘endeavour’d to make Virgil speak such English as he wou’d himself have spoken, if he had been born in England, and in this present Age.’ (307) But if Virgil were alive today, would he have spoken in any of the available vocabularies, and adopted the existing customs? Or would he have forged for himself a new language, and rejected contemporary customs? To assume otherwise, Burrow says, is, as it were, to treat the custom of an age as something universal and inescapable, to which all writers and citizens must submit. Burrow shows that this rather programmatic view of adaptation was popular among royalist writers in the seventeenth century, but was rejected by John Milton, as part of his opposition to the tyranny of custom. When Milton, writing Paradise Lost, imitated the un-rhymed verse of Homer and Virgil, rejecting rhyme as ‘the invention of a barbarous age’ (his own), he was, Burrow says, implying ‘that following ancient example could be a means of escaping from the corrupt conventions of the present, rather than an opportunity to reconstruct those conventions through their present equivalents.’ (310)

Second, many if not most Renaissance commentators also were clear that, no matter how subtle imitation might become – and even if it went far beyond the mere reproduction of the words, or themes, or sentence-structures, rhythms, tones, or images, of one’s models – it could never entirely capture the spirit of the original. That is, in every great author there is not an algorithm but something inimitable. As Francis Junius wrote in 1638, ‘such things as doe deserve to be most highly esteemed in an Artificer, are almost inimitable; his wit, namely his Invention, his unrestrained facilitie of working, and whatsoever cannot be taught us by the rules of Art.’ (301) Quintilian himself, the source of most early modern thought on imitation, had said that ‘the greatest qualities of an orator are inimitable: his talent [ingenium], invention [inventio], force [vis], fluency [facilitas], everything in fact that is not taught in the textbooks.’ (99) Without all this, according to Gianfresco Pico, an imitation would be ‘a mere simulacrum or image which lacks “that genius endowed with its own mysterious energy” […] which Cicero possessed.’ (178)

Categories of Imitation, and their Implications

A perfect imitation is, then, never going to be possible. To ape is not to imitate, and imitation is, therefore, a mistranslation of imitatio, which to its more sophisticated champions and practitioners always meant a far subtler and tentative thing than we might imagine when speak of imitation. How, then, to translate imitatio? A host of English words can make their claim as translations, and their sheer variety points up the range of practices which can be gathered under the title of imitation. In my course on Ludic Literature, I often use parody as a general term for all these practices, because Nabokov did, and because it draws out the playful dimension of imitation which is the subject of the course. But other possibilities could include burlesque, travesty, pastiche, caricature, travesty, transposition, trans-stylization, adaptation, continuation, forgery and translation. Each of these terms has meant many different things at different times. Nevertheless, the French critic Gerard Genette has in his Palimpsests offered the closest thing we have to an encyclopaedia of the practices of imitatio, in which he gives each of these terms a fixed meaning in his system of distinctions, while fully acknowledging that these do not necessarily reflect whatever meanings any of these terms once had.

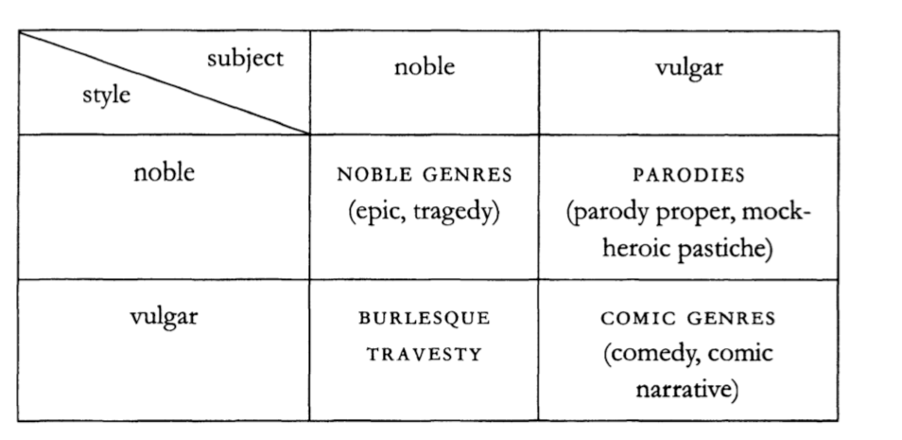

Genette distinguishes along several axes. The first of these is that of the relation between subject and style, the question fundamentally posed by all imitation. When Homer and Virgil were the core texts of Western literature, many variations were worked upon the possibilities of separating the epic style from the epic subject. One might use the noble style of Virgil, but apply it not to a hero fleeing Troy and founding a new civilization in Italy but to a travelling salesman (Genette’s example), or to the squabbles of teenage girls (the most famous such work in English literature, Alexander Pope’s mock-heroic The Rape of the Lock). Conversely, one might preserve the heroic story but apply to it a crass or ‘vulgar’ style – writing about Aeneas and Dido in the language of a tabloid report. Genette distinguishes these, calling the first parody, the second burlesque, or travesty[32]:

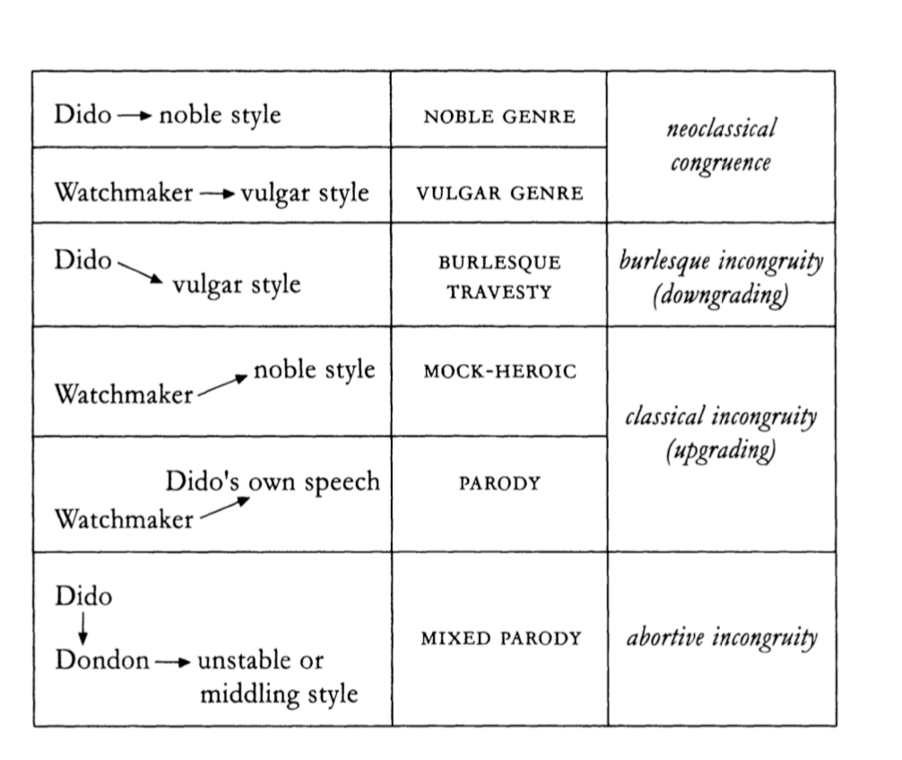

Later in the book, Genette offers a second diagram which clarifies this initial set of distinctions, emphasising the question of whether there is or is not congruence of style and subject (147):

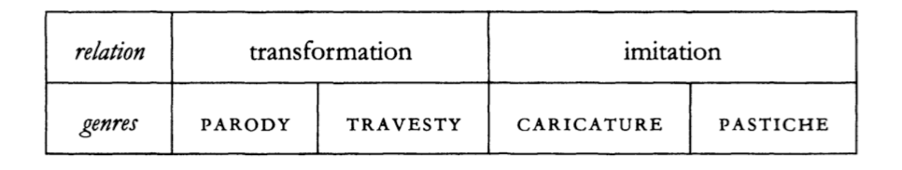

He adds to these distinctions a second set of distinctions, between those re-writings which transform a text by rupturing the style from the subject in one way or another (the parodies and burlesque travesties cited in the first diagram), from those re-writings which comically intensify or earnestly ape the original text, preserving the congruence of the style with the subject (25):

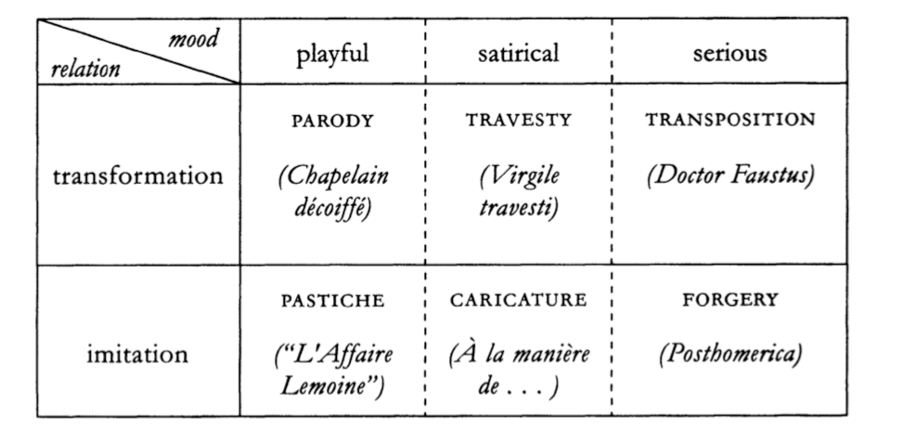

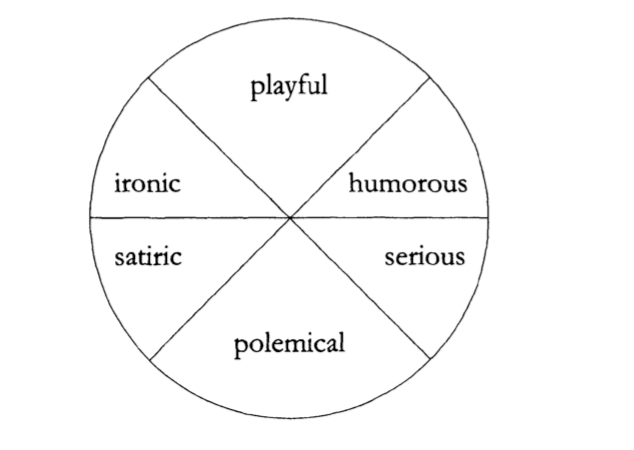

Within this diagram we already see the basis for a third set of distinctions, between re-writings which are satirical and those which are not. In Genette’s terminology, a travesty is a satirical transformation, a parody not; a caricature is a satirical imitation, a pastiche not. But as Genette acknowledges, there is another class of imitations which are not in any way meant humorously (whether satirically or not-satirically). The example he gives is of Mann’s Doctor Faustus. Where such serious re-writings preserve both the style and subject of the original text, they are forgeries. Where they change one or the other, they are in Genette’s terminology transpositions – as where Thomas Mann turns the medieval magician Faustus into a modernist composer in early twentieth-century Germany. This gives rise to a fourth table of distinctions (28):

As Genette adds, the rest of Palimpsests is ‘a long commentary on this chart’, though he adds one final set of discriminations: ‘Between the playful and the satirical, I would readily place the ironic; that is often the mood of Thomas Mann’s hypertexts, such as Doctor Faustus, Lotte in Weimar, and above all Joseph and his Brothers. Between the satirical and the serious divisions, I see the polemical; that is the spirit in which Miguel de Unamuno transposes Don Quixote in his violently anti-Cervantian book The Life of Don Quixote, and that is also the spirit of Henry Fielding’s anti-Pamela, which he titles Shamela. Between the playful and the serious I would add the humorous’ (29):

So much for Genette. Another set of distinctions is offered by Thomas Greene in his The Light in Troy: Imitation and Discovery in Renaissance Poetry (1982). These distinctions are valuable for students in that they address directly the motives and experiences of the imitator, and are specifically framed via the pedagogical and rhetorical theories of the Renaissance. Greene distinguishes between four modes of imitation:

1) the reproductive, or sacramental;

2) the eclectic, or exploitative;

3) the heuristic;

4) the dialectical.

I will here set out what Greene says about each while pausing to add points relevant to this discussion.

The first, sacramental kind of imitation, ‘celebrates an enshrined primary text by rehearsing it liturgically, as though no other form of celebration could be worthy of its dignity.’[33] It includes prayer; copying; memorising; and quotation. For Greene, this is the form of medieval imitation which Renaissance imitation is born from the distinction against: for the fundamental humanist insight of linguistic and cultural change allowed Renaissance scholars and writers to see that to repeat the same words in a different culture is not to repeat their original meaning, but radically to change them. The most famous and vivid modern illustration of this point is to be found in Jorge Luis Borges’s story, ‘Pierre Menard’, in which a French Symbolist writer of the early twentieth-century, rejecting as tasteless ‘carnivals’ ‘those parasitic books which situate Christ on a boulevard, Hamlet on La Cannabiere or Don Quixote on Wall Street’, sets out instead merely to write Don Quixote again: exactly the same words. And yet the text that emerges is, of course, an entirely different one: to Borges’s narrator, and to Menard, far superior to the original. ‘The latter [Cervantes], in a clumsy fashion, opposes to the fictions of chivalry the tawdry provincial reality of his country; Menard selects as his “reality” the land of Carmen during the centuries of Lepanto and Lope de Vega.’ Or, again, Menard follows Cervantes in refusing ‘local colour’ of the kind that had become standard in the historical novels of the 19th century. What was normal to Cervantes, and therefore no artistic statement at all, now appears a bold, even defiant rejection of the norms established by: it ‘points to a new conception of the historical novel.’Cervantes’s style, colloquial in its time, becomes a marked archaicism in Menard. And the phrase in Don Quixote about ‘“truth, whose mother is history”’ – a phrase which in Cervantes is an unnoticed cliché, routine ‘rhetorical praise’, becomes, when copied out by Pierre Menard, an extraordinary provocation: ‘History, the mother of truth: the idea is astounding. Menard, a contemporary of William James, does not define history as an enquiry into reality but its origin.’[34] Changes in culture, language, and the idiosyncracy of the individual writer, can make copying out a radical and creative act. Literature is not a thing, but an event, and an event that is entirely different depending on the scene in which it is staged, even if the script is the same. This, indeed, is the premise of the uncreative writing methods espoused by, among others, the contemporary poet and English Professor Kenneth Goldsmith, who teaches a creative writing class at the University of Pennsylvania in which students are asked merely to choose and copy out bodies of material. As he comments:

the suppression of self-expression is impossible. Even when we do something as seemingly ‘uncreative’ as retyping a few pages, we express ourselves in a variety of ways. The act of choosing and reframing tells us as much about ourselves as our story about our mother’s cancer operation. It’s just that we’ve never been taught to value such choices. After a semester of forcibly suppressing a student’s ‘creativity’ by making them plagiarize and transcribe, she will approach me with a sad face at the end of the semester, telling me how disappointed she was because, in fact, what we had accomplished was not uncreative at all; by not being ‘creative,’ she produced the most creative body of work writing in her life. By taking an opposite approach to creativity — the most trite, overused, and ill-defined concept in a writer’s training — she had emerged renewed and rejuvenated, on fire and in love again with writing.[35]

Conversely, if copying out can be a ‘creative’ act, it can also be a critical one. The act of copying, like that of prayer or memorisation, encourages one to live through every move and decision one’s author makes. As Walter Benjamin writes:

The power of a country road is different when one is walking along it from when one is flying over it by airplane. In the same way, the power of a text is different when it is read from when it is copied out. The airplane passenger sees only how the road pushes through the landscape, how it unfolds according to the same laws as the terrain surrounding it. Only he who walks the road on foot learns of the power it commands, and of how, from the very scenery that for the flier is only the unfurled plain, it calls forth distances, belvederes, clearings, prospects at each of its turns like a commander deploying soldiers at a front. Only the copied text thus commands the soul of him who is occupied with it, whereas the mere reader never discovers the new aspects of his inner self that are opened by the text, that road cut through the interior jungle forever closing behind it: because the reader follows the movement of his mind in the free flight of day-dreaming, whereas the copier submits it to command. The Chinese practice of copying books was thus an incomparable guarantee of literary culture, and the transcript a key to China’s enigmas.[36]

As one allows one’s soul to be ‘possessed’ by the voice of the author one learns the habit of their sentences. It is in fact a practice simultaneously creative and critical, for one learns about another author’s way of writing while also internalising a sense of how to go on with it, as Proust spoke of being able to ‘go on with’ a style for ten volumes once he had acquired its rhythm. When Nabokov taught creative writing students at Stanford in 1941 (a job which had provided the visa that allowed Nabokov and his family to escape Nazi-occupied France), he told them that an aspirant author should: read a couple of pages of some good writer and then try to write down at once as many of his word combinations as can be remembered. A little practice will show that even if the exact words cannot be remembered the lilt of the intonation of the survivors and the extras, the general pattern of those wrong words in the right places – and the very feeling you have of this or that being wrong – will tell you a great deal about the author’s personal style.[37]

Notice especially the final comment, that one may learn most from the very feeling of this or that replica phrase being somehow wrong. For this is the moment when one’s intuitive sense of a style is activated, and the tacit knowledge it embodies is therefore brought to consciousness and potentially made explicit.

The second of Tom Greene’s modes of imitation is what he calls eclectic, or exploitative, ‘where quite simply allusions, echoes, phrases, and images from a large number of authors jostle each other indifferently.’ (39) As Greene says, ‘At its slackest, eclectic imitation falls back into mere anachronism and becomes indistinguishable from the ahistorical citations of the Middle Ages. But when it is employed with artistic intelligence, the imitative poet commands a vocabulary of a second and higher power, a second keyboard of richer harmonies, which however are combined with rhetorical skill rather than esemplastic vision.’ (39) Of Greene’s four forms of imitation, this is, perhaps, of the least interest to us. Yet such miscellaneous and assorted imitation is of particular importance as a predecessor to the critical essays, studded with quotations that are, at their best, provokingly various, which we were taught to write at school and at university. The value of such quotations in essays is precisely that they do not unify – they are not ‘esemplastic’, as Greene puts it. Rather, at best, the critical act consists in constantly testing one style, or author, against another, by placing quotations in various startling new patterns. As Ezra Pound says in the ABC of Reading, ‘the proper METHOD for studying poetry and good letters is the method of contemporary biologists, that is careful first-hand examination of the matter, and continual COMPARISON of one “slide” or specimen with another’; as a piece by Debussy, or Ravel, sounds entirely differently depending on whether it is performed alongside Bach or Corelli.[38] Yet the method of eclectic imitation is not only critical, but also, and simultaneously, creative, as it is in Pound’s Cantos, which set quotations from wildly disjunctive sources against one another in the aim of making each come alive in a new light. In truth, was the pleasure of writing such essays not always, most of all, in the creative pleasure of copying out the quotations, and thus making them our own? And does that pleasure not offer a clue to the true essence of the critical essay: namely, that it is an attempt at literary creation, not critical understanding?

The third of Greene’s categories of imitation is that which he calls the heuristic, which ‘come to us advertising their derivation from the subtexts they carry with them, but having done that, they proceed to distance themselves from the subtexts and force us to recognize the poetic distance traversed.’ (40) Here two languages, cultures, styles, are held in a tense relation to one another. The transition is possible, albeit imperfect, and these imperfections teach us about both the origin and the destination. This is, for our purposes, the main form of ‘imitation’, and many if not most of the versions of imitation which Genette itemises could be placed in this category. Thus Joyce’s Ulysses sets early twentieth-century Dublin, and the various forms of prose available, against Homer’s Odyssey – neither to assert nor to deny that Bloom is a second Odysseus, or that Joyce’s exquisite prose, which bends the sentence into such varying shapes to track the chain of associations in a mind, is somehow translatable into Homer’s epic hexameters, with their divinities and monsters. Likewise, Milton’s Paradise Lost sets the Christian story, and the English Revolution, in and against the world of Virgil and Augustus – as Virgil had done with Homer. But, Greene says, although ‘Paradise Lost looks at first glance also to depend on an eclectic strategy’, ‘in fact it establishes firmly a strong if sometimes complex relationship with each work and each tradition that it draws upon, according to each its own cultural weight and situation. It underscores rather than obscures the historicity of its sources, and so it permits a flood of imaginative energy to flow through it unimpeded.’ (40) Heuristic imitation, in Greene’s sense, ‘dramatizes a passage of history, builds it into the poetic experience as a constitutive element’, and ‘acts out its coming into being’ from its historical sources. ‘The passage of this rite moves not only from text to text but from an earlier semiotic matrix to a modern one.’ (41)

But for this miracle of translation to occur, the writer must offer themselves as the medium, in the fullest sense. They must search both for a voice in the origin text which is capable of speaking across time and space, and discover a voice within themselves capable of picking up, re-transmitting, and broadcasting that voice. In performing this ‘ballet of latencies’ (42), as Greene calls, it the imitating author not only ‘subreads’ the origin text but must ‘subread’ themself, listening to and analysing their own inner voices: ‘The subject who attempts to subread must be ready to play with subjective styles of perception, must question and test himself as he sharpens his intuitions, must finally subread his own consciousness to discern that inner likeness, that virtual disposition capable of conversing with a voice from the depths of time.’ (96) ‘Imitation at its most powerful pitch required a profound act of self-knowledge and then a creative act of self-definition.’ (96) Or, Greene offers a second metaphor, comparing the writer who attempts such an act of imitation to the infant acquiring self-consciousness by seeing its face reflected in its mother’s gaze; only, to complete the metaphor, the writer must feel that their maternal origin – Virgil to Milton, Homer to Joyce – is, as it were, looking back at them.

Yet as Greene makes clear, this mirroring of gazes will never be perfect; indeed, it must not be, otherwise the two faces, merging, would each be lost. There would always be a sense of qualities untranslatable between voices, styles, and languages. ‘The whole enterprise sustained conflicts between intuitions of intimacy and intuitions of separation, between the belief in transmission and the acceptance of estrangement.’ (45) This unbridgeable distance, however, was also an opportunity. ‘The text cannot simply leave us with two dead dialects. It has to create a miniature anachronistic crisis and then find a creative issue from the crisis.’ (42) That is to say, that as an author seeks to imitate a previous author, flaws are exposed in each author, in each culture, which make possible an act of creation which is also an act of criticism that may begin at the level of style but will rarely end there, but rather turn out to encompass all the ideological and cultural issues that are at play in that style – or which, rather, may previously have been concealed in it. It is this that makes such imitation ‘heuristic’ in Greene’s sense: that is, the failures of imitation serve as swift indicators of the differences in languages and cultures and help us to understanding.

Taken one step further, this intrinsic incompleteness in the exchange of imitation leads to Greene’s fourth category of imitation, which he calls the dialectical. Here comes to the fore the element of conflict always potential in the gap between the imitator and imitated. Understanding is sharpened into criticism. Now the passage of time comes to be seen as fundamentally discontinuous, styles untranslatable, and each era is exiled from the flow of providence, and left shivering alone on the various islands of secular history. ‘By exposing itself in this way to the destructive criticism of its acknowledged or alleged predecessors, by entering into a conflict whose solution is withheld, the humanist text assumes its full historicity and works to protect itself against its own pathos.’ (46) Or, again, such a text must ‘prove its historical courage and artistic good faith by leaving room for a two-way current of mutual criticism between authors and between eras.’ (45) This ‘dialectical imitation’ is, Greene says, characteristic of parody, which, as he says, ‘always engages its subtext in a dialectic of affectionate malice.’ (46) In parody, and in dialectical imitation, the element of criticism, in the modern sense, becomes explicit: the work of art implies the sort of analytic understanding of its own culture, and it styles, as of those of the imitated work. It is a different but related artistic source for literary criticism to that we found in the practice of eclectic imitation.

This final category, the dialectical, forces upon us an awareness of the gaps and flaws in both the source and the target styles. If I translate, say, Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ into the voice of Eliot’s Middlemarch, I immediately notice certain gains: how I can draw individual actions into a larger philosophical vision of human existence, humanised by sophisticated ironies which play between various perspectives that Eliot’s long varied sentences organise without homogenising. I see the lack of this in Joyce, how his nose-to-the-ground intensity on the truth in detail denies us the sort of stereoscopic wisdom we rejoice in in Eliot. We might have felt this lack when we read ‘The Dead’, but without bringing it to consciousness: that is the power of a strong style such as Joyce’s, that it persuades one to accept its vision so completely as to exclude the thought of alternatives. But conversely, when we make this translation of Joyce into Eliot, we will also notice the losses. Gone are Joyce’s eloquent silences and his carefully orchestrated harmony of dissonances. Can Eliot’s style really accommodate, for example, the complexity of the effect at the end of ‘The Dead’, in which the sentiment in an old ballad is given to us as at once sentimental and false, and yet – in some other less secularly psychological sense – as utterly true?

Thus the charisma of a style, which renders invisible its assumptions about the world, is defeated by a truly dialectical, critical, transposition, which breaks its forms. This is still more obviously so in the case of a kind of imitation or transposition to which Greene pays relatively little attention – that is, transposition from one literary form to another, of the kind Genette describes in his chapters on ‘prosification’ and ‘versification’ (turning verse into prose, or prose into verse), and in his accounts of ‘dramatization’ and ‘narrativization’ (turning prose into drama, or drama into prose). But these are broad categories. One may, for example, turn a Petrarchan sonnet into a Shakespearean one. I have often taught a clear example of this happening by setting alongside one another Wyatt’s translation of Petrarch’s Sonnet 140, which adheres to the Petrarchan cdecde rhyme scheme with a fixed ababcdcd octave and a variable sestet (eg cdecde), and Surrey’s somewhat later translation of the same poem into the rhyme scheme, ababcdcdefefgg, which Shakespeare later used for his sonnets – a form which diminishes the separation of octave and sestet and closes with a final couplet. Setting Wyatt’s version, ‘The long love that in my heart doth harbor’, against Surrey’s later ‘Love that doth reign and live within my thought’, allows us to compare not only the effect of different word-choice and order, but also what each form is capable of. Thus, for example, we discuss how Wyatt’s form, with its interlacing rhymes, allows for the reader to perceive its internal structure in various different patterns, and thus to see the relations between the various themes and conceits diversely; or we comment on what difference it makes when a final couplet seals off the emotional chaos of Petrarch’s material, extracting from it the compact wisdom of a theme or an aphorism – analogous even, I suggest, of the conclusion of a methodical essay.

The point is not that all sonnets in the Petrarchan form say one thing by their forms, or shape material in one emotional pattern, and all sonnets in the Surreyan or Shakespearean form another. It is, rather, that each form has certain potentials which one can only learn about by seeing that potential being tried in various unpredictable contexts; and which one also learns about by seeing those forms bent, broken, and transformed. This view of forms has recently been popularised by Caroline Levine, who in her book Forms speaks of a form’s ‘affordance’, a term she borrows from design theory. It is ‘a term used to describe the potential uses or actions latent in materials and designs.’ The power of the term is that it allows us to see not only what a form is capable of, and how these capacities are carried with the form across time and space, but also that we learn new things about a form by the new uses it proves itself capable of. ‘A specific form can be put to use in unexpected ways that expand our general sense of that form’s affordances.’[39] As it happens, this powerful idea had been expressed by Ezra Pound in the ABC of Reading – a book I have already referred to – and in a form which anticipates Levine’s metaphor of a literary form as a material, but which adds to it a slightly different thought: that to know a form, or a style, one must not merely test it in new and unpredictable circumstances to see what it is capable of; one must also place it against alternative and alien styles and forms: ‘The way to study Shakespeare’s language is to study it side by with something different and of equal extent. / The proper antagonist is Dante, who is of equal extent and DIFFERENT. […] You can’t judge any chemical’s action merely by putting it with more of itself. To know it, you have got to know its limits, both what it is and what it is not. What substances are harder or softer, what more resilient, what more compact.’[40]

The confrontation between alien styles and forms that one finds in what Greene calls dialectical imitation makes for a distinct and multifarious pleasure that deserves scrutiny. It is, among other things, the pleasure of seeing the vast metamorphoses of which forms of discourse are capable – how far they can be portaged without being lost, how much they imply within themselves. Is this not, in fact, some of the pleasure we all had, at school, when we first discovered that we could take a poem by Donne, a play by Shakespeare, or a novel by Austen, and turn it into – of all things – a methodical essay? What a delightfully bizarre transposition. And yet, in the new form of the essay, we could see emerging in wonderfully strange and novel disguise thoughts, images, emotions which we could recognise as those we had already seen in ‘The Sun Rising’, or Pericles, or Emma – and yet recast in the guise of rational ideas, such as our culture is able to respect. To watch such a metamorphosis was to be granted a new esteem for the literary forms which our culture usually patronises: see how much there is ‘in’ Emma: isn’t Austen really every bit as clever as Terry Eagleton! But it also seemed to pay a compliment to the methodical essays which had so fully formed our intelligences as to seem nearly equivalent to them, that such essays could accommodate the images, dramas, and ironies of the works of literature we cared about.

One part of the pleasure of such radical metamorphoses of style and form may be this fascination of seeing how much can be preserved and accommodated in otherwise apparently alien forms. But another part of the pleasure may be just the opposite. The writer, the reader, the student, who finds themselves the medium in which two incompatible styles or forms converge and clash is happily freed from the authority of either. No model for imitation is dominant. Choice, and therefore thought, become possible. In the classroom, this makes for the quality Ben Knights has eloquently described in the best literature teaching, as in his recent book Pedagogic Criticism, where he says that at best, the teaching of English makes for ‘a threshold, a liminal or transitional space’, in which the voices of various texts enter into dialogue with the voices of the teacher and the class members.[41] None are dominant, and none are resolved. As a result of this, the students come to experience how they themselves are constituted by various intersecting discourses. At one moment, or another, a different inner voice is awoken in the individual student; and the student is given the opportunity to trace its origins, in the discourses that surround them, in the works of literature they are engaging with, in their teachers and fellow students; and to analyse the implications of their voices. The English classroom at its best can make visible that ‘intersubjective zone’ in which, Knights and Chris Thurgar quote David Shotter as saying, ‘“The ‘movement ’ of my inner life is motivated and structured through and through by my continual crossing of boundaries; by what happens in those zones of uncertainty where ‘ I ’ (speaking in one of my ‘ voices ’ from a ‘ position ’ in a speech genre) am in communication with another ‘ self ’ in another position within that genre.”’[42] In this zone, ‘the meaning of the text, like the identity of the learner, is summoned into being in conversation (hesitant, non-linear, tentative as that may be) between readers or between students and their teachers.’[43]

[1] Thomas Roebuck, ‘Reading and Writing in Elizabethan England’, UEA module.

[2] Will Rosseter, ‘Unlike Them All, and Better? Englishing the Italian Renaissance’.

[3] Thomas Karshan, ‘Ludic Literature’, UEA modules, 2020.

[4] Catherine Maxwell, ‘Teaching Nineteenth-century Aesthetic Prose: A writing-intensive course’, Arts & Humanities in Higher Education, Vol 9:2 (2010), 191 – 204.

[5] Nick Everitt, ‘Creative Writing and English’, Cambridge Quarterly (2005), 231 – 242.

[6] Christoff, Reckson, and Dolven, in Diana Fuss & William Gleason, eds., The Pocket Instructor – Literature: 101 Exercises for the college classroom (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), 272-81.

[7] Roger Gilbert, in Approaches to Teaching the Works of Gertrude Stein, ed. Logan Esdale and Deborah Mix, (New York: The Modern Languages Association of America, 2018), 121 – 128 (here 127 – 8).

[8] Tim Dooley, ‘Sappho to Bashō and beyond’, course taught at The Poetry School. INSERT LINK HERE.

[9] Thomas Karshan, Vladimir Nabokov and the Art of Play (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[10] See T. W. Baldwin, William Shakspere’s Small Latin and Less Greek, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1944), 2 Vols, and Donald Lemen Clark, John Milton at St. Paul’s School (Columbia: Columbia University Press, 1948).

[11] Aristotle, Ethics, in The Complete Works of Aristotle, edited by Jonathan Barnes. 2 vols. (New York: Random House, 1944), 1448b5. Cited in Jeff Dolven, Senses of Style: Poetry before Interpretation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 109.

[12] Jeff Dolven, Scenes of Instruction in Renaissance Romance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 22.

[13] Baldwin, William Shakspere’s Small Latin and Less Greek, Vol. 1, 88; 155; 160; 265; 272.

[14] Baldwin, William Shakspere’s Small Latin and Less Greek, p. 94.